43

MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS:

PROPERTY RIGHTS AS A BULWARK

AGAINST DNS CENSORSHIP

NICHOLAS NUGENT*

It is increasingly becoming the practice of domain name system

(DNS) intermediaries to seize domain names used by lawful

websites for violating acceptable use policies related to offensive

content or hate speech. Website hosting companies and social media

platforms, entities that use but do not operate core Internet

infrastructure, have long reserved and exercised their rights to gate

their offerings, leaving booted speakers free to migrate to other

providers. But registrants deprived of their domain names lack

similar options to maintain their presence in cyberspace. The loss of

a domain name inexorably results in the takedown of any website

that uses the domain name, even if hosted elsewhere, and leaves a

potentially invaluable asset essentially free for the taking by

another. Proponents of Internet freedom have therefore argued that

companies that operate foundational Internet infrastructure, such

as the DNS, should play no role in policing content, no matter how

deplorable, and that DNS censorship, once normalized, could easily

spread to other minority groups and viewpoints.

Acknowledging that DNS intermediaries—the companies that

offer domain names and make them operational on the Internet—

are private actors whose actions are not subject to First Amendment

constraints, critics of DNS censorship seem to tacitly concede that

DNS intermediaries may take whatever actions are permitted under

their terms of service, appealing instead to policy arguments or calls

to enact new protective legislation. But I argue that registrants

already possess the legal means to protect themselves from domain

name seizure through the property rights they acquire in their

domain names.

* I would like to thank Christopher Yoo, Michael Froomkin, Milton Mueller, Ryan

Calo, and Konstantinos Komaitis for helpful feedback and suggestions during the

drafting process. Thanks also to Alexandra Bakalar for all the great research assistance.

Original illustrations use icons made by Freepik and Kiranshastry from

www.flaticon.com. The views expressed herein are entirely my own and do not

necessarily reflect any policy positions held or endorsed by any current or former clients

or employers.

44 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

Although the property status of domain names is by now fairly

well established in the case law, scant attention has been paid to the

precise nature of registrants’ interests in that property. Making the

case that registrants take title to their domain names upon

registration, I argue that registrants may state valid claims under

conversion and trespass to chattels when DNS intermediaries

attempt to seize lawfully registered and operated domain names in

the absence of court orders, despite the contractual rights such

intermediaries purport to reserve to themselves. I further explore

how federal law could supplement these existing common law

protections by enshrining domain names as a new class of

intellectual property.

INTRODUCTION................................................................................... 45

I. TECHNICAL OVERVIEW OF THE DNS .......................................... 49

A. IP Addresses and Domain Names ..................................... 49

B. DNS Intermediaries ............................................................ 56

II. DNS INTERMEDIARY POWER OVER CONTENT ............................ 64

A. Cybersquatting & Restrictions Against Illegal Content ... 64

B. Restrictions against Legal Content .................................... 72

C. Examining DNS Censorship .............................................. 78

1. “Dumb Pipes” ................................................................. 79

2. Censorship Creep and Collateral Censorship ............. 81

3. Disproportionate Effects ............................................... 84

III. PROPERTY RIGHTS IN DOMAIN NAMES ....................................... 88

A. Domain Names as Contractual Rights .............................. 88

B. Domain Names as Property ................................................ 90

C. Shakeout and the Merger Requirement ............................. 91

1. Other Courts .................................................................. 91

2. Merger Requirement ..................................................... 93

D. Resolving the Debate ........................................................... 94

1. Property Theory ............................................................ 95

2. Federal Support............................................................. 96

3. Service Separability ...................................................... 97

E. Nature of the Property Interest ........................................... 99

1. Case Law ...................................................................... 100

2. Property Theory .......................................................... 102

3. No Better Claimant to Title ....................................... 107

4. A Thought Experiment ............................................... 112

IV. PROPERTIZATION AS A BULWARK AGAINST DNS CENSORSHIP 114

A. How Property Law Protects Registrants .......................... 115

1. Repossession ................................................................ 116

2. Execution ..................................................................... 116

3. Bailment ...................................................................... 117

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 45

4. Liquidated Damages ................................................... 118

5. Domain Name Seizure as Tortious Conversion ........ 119

B. Where Property Law Falls Short...................................... 122

1. Heterogeneous Treatment under State Law ............. 123

2. Registrars .................................................................... 124

3. Registry Operators ...................................................... 124

C. Filling the Gaps ................................................................ 127

1. Federal Law ................................................................. 127

2. Top-Down ICANN Policy ............................................ 130

3. Alternative DNS .......................................................... 130

CONCLUSION .................................................................................... 131

INTRODUCTION

In August 2017, GoDaddy, the world’s largest domain name

registrar and website hosting provider, served notice to

DAILYSTORMER.COM that the website had twenty-four hours to

move its domain name to another registrar before the domain would

be canceled.

1

Daily Stormer, GoDaddy alleged, had violated the

latter’s terms of service by hosting website content mocking the

death of Heather Heyer, a woman killed in the course of protesting

a white nationalist rally.

2

Within hours of moving to Google’s

domain management service, Google followed suit by first

suspending

3

and then canceling Daily Stormer’s domain name.

4

In October 2018, GoDaddy issued a similar eviction notice to

GAB.COM, the so-called “free speech Twitter,”

5

for hate speech

1. Daniel Van Boom & Claire Reilly, Neo-Nazi Site The Daily Stormer Down After

Losing Domain, CNET (Aug. 14, 2017, 11:19 PM), https://www.cnet.com/news/neo-nazi-

website-daily-stormer-to-lose-domain-name [https://perma.cc/DPW8-7VW9]; see also

Domain Name Registrar Stats, DOMAINSTATE, https://www.domainstate.com/registrar-

stats.html [https://perma.cc/Q3DN-VU92] (last visited Nov. 5, 2020) (for GoDaddy’s

share of global domain name and hosting market).

2. Bill Chappell, Neo-Nazi Site Daily Stormer Is Banned By Google After Attempted

Move From GoDaddy, NPR (Aug. 14, 2017, 8:30 AM),

https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/08/14/543360434/white-supremacist-

site-is-banned-by-go-daddy-after-virginia-rally [https://perma.cc/NZT9-EPST].

3. Michele Neylon, DailyStormer Offline as Google Pulls Domain Registration,

INTERNETNEWS (Aug. 15, 2017), https://www.internetnews.me/2017/08/15/dailystormer-

offline-google-pulls-domain-registration [https://perma.cc/HEY6-KMZB].

4. Jim Finkle, Neo-Nazi Group Moves to ‘Dark Web’ After Website Goes Down,

REUTERS (Aug. 15, 2017, 7:42 AM), https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-virginia-protests-

daily-stormer-idUKKCN1AV1I0 [https://perma.cc/4CWD-E6SJ].

5. Kassy Dillon, Introducing ‘Gab’: Free Speech Twitter Alternative, WASH.

EXAMINER (Aug. 21, 2016, 11:07 AM), https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/red-alert-

politics/introducing-gab-free-speech-twitter-alternative [https://perma.cc/N8UX-D9EG].

46 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

posted by users on the website.

6

When Gab proved unable to

transfer its domain name to another registrar within twenty-four

hours, GoDaddy suspended the domain, effectively taking the

website down until another registrar was found.

7

One month later,

DoMEn d.o.o., the company responsible for managing the .ME top-

level domain, suspended INCELS.ME, a domain name used by a

forum for “involuntary celibates,” after the website failed to remove

user content that promoted violence.

8

The domain name remained

offline for more than a year thereafter.

9

These actions were consistent with a broader trend in which

domain name system (DNS) intermediaries, such as registrars and

registry operators, have begun to take a more active role in policing

website content through their control over Internet domain

names.

10

This trend began with efforts by DNS intermediaries to

combat online piracy and quickly expanded to other categories of

illegal conduct, such as child pornography and “rogue” online

pharmacies.

11

However, the new form of content regulation that

brought down DAILYSTORMER.COM, GAB.COM, and

INCELS.ME differed from previous campaigns by DNS

intermediaries in one important respect: it concerned legal content.

In all three cases, the basis for suspension was community speech

found on the registrants’ websites that, although certainly

offensive, was fully protected under the First Amendment.

While some groups have cheered these developments and

urged DNS intermediaries to play a stronger role in combating hate

speech,

12

advocates of online freedom have argued that, unlike

Internet service providers or social media networks, DNS

intermediaries do not host or transmit any content and therefore

6. Catherine Shu, Far-right Social Network Gab Goes Offline After GoDaddy Tells

it to Find Another Domain Registrar, TECHCRUNCH (Oct. 28, 2018, 11:28 PM),

https://techcrunch.com/2018/10/28/far-right-social-network-gab-goes-offline-after-

godaddy-tells-it-to-find-another-domain-registrar [https://perma.cc/R462-HSYT].

7. Id.

8. The Suspension of Incels.me, .ME (Nov. 20, 2018), https://domain.me/the-

suspension-of-incels-me [https://perma.cc/4V2L-UALA]; Matt Binder, Incels.me, A Major

Hub for Hate Speech and Misogyny, Suspended by .ME registry, MASHABLE (Nov. 20,

2018), https://mashable.com/article/incels-me-domain-suspended-by-registry

[https://perma.cc/VT83-MJ85].

9. Id.

10. See Michael Kunzelman, Online Registrar Threatens to Drop Anti-Immigration

Website, ABC NEWS (June 22, 2020, 3:16 PM),

https://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/online-registrar-threatens-drop-anti-

immigration-website-71391728 [https://perma.cc/9ZJT-KQNA] (describing Web.com’s

threats to suspend VDARE.COM for its anti-immigration views).

11. See infra Part II.A.

12. See, e.g., FAQs, CHANGE THE TERMS, https://www.changetheterms.org/faqs

[https://perma.cc/VG2E-5VR4] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (promoting the work of a

coalition of civil rights groups to encourage technology companies to use their terms of

service to curb “hateful activity,” including, notably, companies that provide domain

name services).

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 47

should play no role in policing speech that is external to their

systems.

13

The latter fear that allowing private domain name

companies to effectively boot entities from the Internet based on the

expressive content of websites risks creating tools of censorship

that could be leveraged in the future to suppress other viewpoints

or causes.

14

Commentators have also noted with alarm the lack of

due process protections that often accompany domain name

takedowns, whether for legal or illegal conduct.

15

But even assuming we want domain name companies to

operate the DNS in a content-neutral manner—a goal I assume in

this article—it might seem that little can be done to ensure that

outcome. DNS intermediaries are private actors, and the Supreme

Court has long held that the First Amendment does not protect

speech from censorship by private actors, with limited exceptions

that have not been extended to cyberspace.

16

And although the

United States used to exercise oversight over the Internet

13. See, e.g., Jeremy Malcom, Cindy Cohn & Danny O’Brien, Fighting Neo-Nazis

and the Future of Free Expression, ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUND. (Aug. 17, 2017),

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2017/08/fighting-neo-nazis-future-free-expression

[https://perma.cc/5KKV-WZQM] (“Companies that manage domain names, including

GoDaddy and Google, should draw a hard line: they should not suspend or impair domain

names based on the expressive content of websites or services.”) [hereinafter Malcom et

al., Fighting Neo-Nazis].

14. Id. (“[W]e must also recognize that on the Internet, any tactic used now to silence

neo-Nazis will soon be used against others, including people whose opinions we agree

with.”); see also Michael C. Dorf, Free Speech Issues Raised by Internet Companies

Denying Service to Neo-Nazi Sites, VERDICT (Aug. 23, 2017),

https://verdict.justia.com/2017/08/23/free-speech-issues-raised-internet-companies-

denying-service-neo-nazi-sites [https://perma.cc/H8CW-QDH6] (posing hypotheticals of

other groups or causes that could be de-platformed by means of DNS takedown); Will

Oremus, GoDaddy Joins the Resistance, SLATE (Aug. 16, 2017, 2:10 PM),

https://slate.com/technology/2017/08/the-one-big-problem-with-godaddy-dropping-the-

daily-stormer.html [https://perma.cc/SPW8-5BFU] (“Cutting off domain hosting is a

potent weapon against the purveyors of objectionable content—and it could be double-

edged.”).

15. See, e.g., Jeremy Malcolm & Mitch Stoltz, How Threats Against Domain Names

Are Used to Censor Content, ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUND. (July 27, 2017),

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2017/07/how-threats-against-domain-names-used-censor-

content [https://perma.cc/9AA7-3G85] (noting the lack of due process protections for

registrants whose domain names are taken down for service violations) [hereinafter

Malcolm & Stoltz, Threats]; Annemarie Bridy, Notice and Takedown in the Domain

Name System: ICANN’s Ambivalent Drift into Online Content Regulation, 74 WASH. &

LEE L. REV. 1345, 1385 (2017) (“Lack of transparency and due process in such programs

will make them inherently vulnerable to inconsistency, mistake, and abuse and could

transform the DNS into a potent tool for suppressing disfavored speech.”) [hereinafter

Bridy, Notice and Takedown].

16. See Christopher S. Yoo, Free Speech and the Myth of the Internet as an

Unintermediated Experience, 78 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 697, 699, 702 (2010) (“Under

current law, the First Amendment only restricts the actions of state actors and does not

restrict the actions of private actors.”) and (“[F]ree speech considerations favor

preserving intermediaries’ editorial discretion unless the relevant technologies fall

within a narrow range of exceptions, all of which the Court has found to be inapplicable

to the Internet.”).

48 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN)—the non-

profit corporation that sets policy for the DNS—that power was

relinquished in 2016 when the United States permitted ICANN to

transition to a global multi-stakeholder governance model.

17

DNS

intermediaries thus have wide latitude, it would seem, to impose

content-based restrictions on domain name registrants through

their terms of service and to enforce those terms through the self-

help remedies of domain name suspension, cancellation, and

transfer.

In this article, I argue that one potential bulwark against

content regulation by DNS intermediaries—one that has been

largely overlooked—is registrants’ property rights in their domain

names. Although once the subject of debate between different lines

of cases, both federal and state courts in the United States have

largely settled on the proposition that domain names are a form of

personal property and that a registrant may state a claim for

conversion against an entity that unlawfully interferes with that

property.

18

Thus far, such conversion claims have been brought

almost exclusively in situations where one registrant manages to

appropriate another registrant’s valuable domain name in order to

commercialize the name for its own purposes.

19

In other words, the

goals of both plaintiff and defendant have been the same: to use the

domain name for a website. However, if we take the property nature

of domain names seriously, we see that similar conversion claims

could be made by domain name owners against DNS intermediaries

who suspend, cancel, or transfer domain names in the absence of

court orders or similar legal processes. Consulting the closest

available analogs in disparate areas of law such as repossession,

bailment, and liquidated damages, I argue that such property

rights may even suffice to override explicit contractual terms

granting DNS intermediaries the right to seize domain names for

breach of contract.

This article proceeds as follows. Part I presents a technical

overview of the DNS with a particular view to separating core DNS

services from non-core and value-added services that

intermediaries might provide. Part II analyzes various provisions

in DNS intermediary service contracts that purport to empower

DNS intermediaries to regulate content. It also describes ways,

both systematic and ad hoc, in which DNS intermediaries have

exercised that power. Part III traces the historical debate as to

17. See ICANN’s Historical Relationship with the U.S. Government, ICANN,

https://www.icann.org/en/history/icann-usg [https://perma.cc/MH7S-SYQG] (last visited

Oct. 18, 2020) (detailing the multi-year process by which the U.S. Department of

Commerce turned control of ICANN over to a system of global stakeholders).

18. See infra Parts IV.A–C.

19. See Kremen v. Cohen, 337 F.3d 1024, 1035 (9th Cir. 2003).

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 49

whether domain names should be classified as property versus

mere contractual rights. It explains how the property view of

domain names has become the consensus position and shows why

this view is correct. It further analyzes the previously ignored issue

of which party holds title to a registered domain name and

concludes that only the registrant could legitimately be regarded as

the owner. Finally, Part IV argues that a robust doctrine of domain

names as property can be used to cabin intermediaries’ private

regulatory power. It explains how common law claims of conversion

or trespass to chattels could be brought against DNS intermediaries

who interfere with domain names in response to legal, or perhaps

even illegal, web activity. But it notes the legal and practical

limitations of such common law remedies and, therefore, explores

additional potential options for strengthening property rights, such

as through federal legislation that would recognize domain names

as a new and distinct class of intellectual property.

I. TECHNICAL OVERVIEW OF THE DNS

Although many primers already exist that describe the

structure and operation of the DNS, the arguments presented in

this article turn on specific technical and historical nuances that

are either absent from introductory descriptions or otherwise

buried within advanced texts on the subject. Hence, in this Part, I

aim to survey the DNS in a way that covers some of the more

specialized details omitted by other summaries while remaining

accessible to a generalist audience. Section A explains how users

and computers use domain names in real time to locate content on

the Internet. Section B describes the roles played by various

intermediaries in that process.

A. IP Addresses and Domain Names

At the heart of nearly all modern Internet communication lies

the mighty Internet Protocol (IP) address, a unique, 32-bit

identifier represented as a string of up to twelve digits—for

example, 93.184.216.34—that indicates the logical location of a

device on the public Internet.

20

For a first computer (a client) to

communicate with a second computer (a host), the client must

append the host’s IP address to any message it sends, and the host,

20. This definition and the explanation that follows assume the use of IPv4

addresses which are still used by most Internet devices. Although a movement is under

way to convert all public Internet traffic to the more flexible and capacious IPv6

standard, that development is not germane to this article and has no bearing on its

arguments. See generally Andy Patrizio, IPv4 vs. IPv6: What’s the Difference? AVAST

(May 8, 2020), https://www.avast.com/c-ipv4-vs-ipv6-addresses [https://perma.cc/7JUY-

G9MW].

50 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

in turn, must append the IP address of the client in any response.

But twelve-digit strings are difficult for users to remember, and so

the domain name system (DNS) was devised to make it easier for

users to access resources on the Internet without having to

remember IP addresses.

21

Fundamentally, the concept behind the DNS is quite simple:

create a list (a registry) that maps alphanumeric hostnames to IP

addresses—e.g., “UCLA_server: 137.117.9.38”—then, when a user

wishes to access an Internet resource, such as a website, she need

only enter the hostname into her browser. The registry is consulted

to find the IP address of the host (here, a web server), and then the

user’s computer uses the IP address to request the resource (here,

a web page) from the host. As a result, the user no longer needs to

know the IP address of any website to access it. She need only know

the hostname, and the DNS and her computer will take care of the

rest.

Building upon this basic concept, the architects of the early

Internet designed the DNS with several important enhancements

including top-level domains, authoritative registries, and caching.

Starting with top-level domains, as the number of servers

connected to a network increased, so did the risk of naming

collisions, wherein two different entities seek to use the same

hostname.

22

One solution to this problem was to create separate

zones, also known as “domains,” for hostnames based on the type or

purpose of the host. Accordingly, in 1984, the Internet Engineering

Task Force (IETF) published RFC 920, which proposed the creation

of six “top-level domains” (TLDs), including COM (commercial),

EDU (education), GOV (government), and ORG (a catch-all for

other organizations).

23

The result was the modern “domain name”

syntax that remains in use today, in which a top-level domain (e.g.,

COM) follows a second-level domain (e.g., MICROSOFT) with the

two strings separated by a dot—hence, MICROSOFT.COM. This

design permits two different entities to use the same hostname in

different domains—e.g., FMC.COM (Ford Motor Company) vs.

FMC.EDU (Fine Mortuary College)—without any conflict.

Next, for a name-to-address mapping to be effective, it must be

globally consistent. It will not do for some clients to map

FACEBOOK.COM to one set of IP addresses while other clients

map it to a different set. Moreover, if Facebook elected to change an

21. Frederick M. Abbott, On the Duality of Internet Domain Names: Propertization

and Its Discontents, 3 N.Y.U. J. INTELL. PROP. & ENT. L. 1, 3 (2013) (“[T]he domain name

is the ‘human friendly’ way of solving the memory and data entry problem.”).

22. NAT’L RESEARCH COUNCIL, SIGNPOSTS IN CYBERSPACE: THE DOMAIN NAME

SYSTEM AND INTERNET NAVIGATION 41 (2005).

23. See J. Postel & J. Reynolds, Request for Comments 920: Domain Requirements,

INTERNET ENGINEERING TASK FORCE 7–8 (Oct. 1984), https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc920

[https://perma.cc/6VJS-4Q32].

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 51

IP address, some mechanism must exist to inform any clients using

the old IP address to switch over to the new address. Hence, at the

core of the modern DNS is the concept of authoritative registries.

For each top-level domain, a single entity known as a “registry

operator” maintains an authoritative zone file that contains

information for all domain names registered within the top-level

domain.

24

For example, Verisign, Inc., which operates the .COM

top-level domain, maintains the authoritative zone file for all .COM

domain names.

25

Any computer may therefore determine the IP

address for any .COM domain name by sending a DNS query to

Verisign’s nameservers.

But because it would strain a registry operator’s servers to

respond to a DNS query every time a computer uses a domain

name, the DNS makes extensive use of caching. When a

nameserver responds to a DNS query with authoritative IP address

information about a domain name, its response also includes a

“time-to-live” (TTL) value, which can range from seconds to days,

indicating how long the information should be regarded as valid.

Any computers receiving the response are expected to store (cache)

the information in memory and use it for all future communications

involving the domain name, rather than querying the registry

operator each time, until the TTL expires, at which time the DNS

information is deleted from cache.”

24. See GlobalSantaFe Corp. v. Globalsantafe.com, 250 F.Supp.2d 610, 618–19 (E.D.

Va. 2003); NAT’L RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 22 at 120–21; MARK E. JEFTOVIC,

MANAGING MISSION-CRITICAL DOMAINS AND DNS 32 (2018). Registry operators are

sometimes referred to simply as “registries.” To avoid any confusion with the registry

databases maintained by registry operators, this article uses the long form “registry

operators” throughout.

25. See Root Zone Database, INTERNET ASSIGNED NUMBERS AUTHORITY,

https://www.iana.org/domains/root/db [https://perma.cc/KUN5-H7UD] (last visited Oct.

18, 2020).

52 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

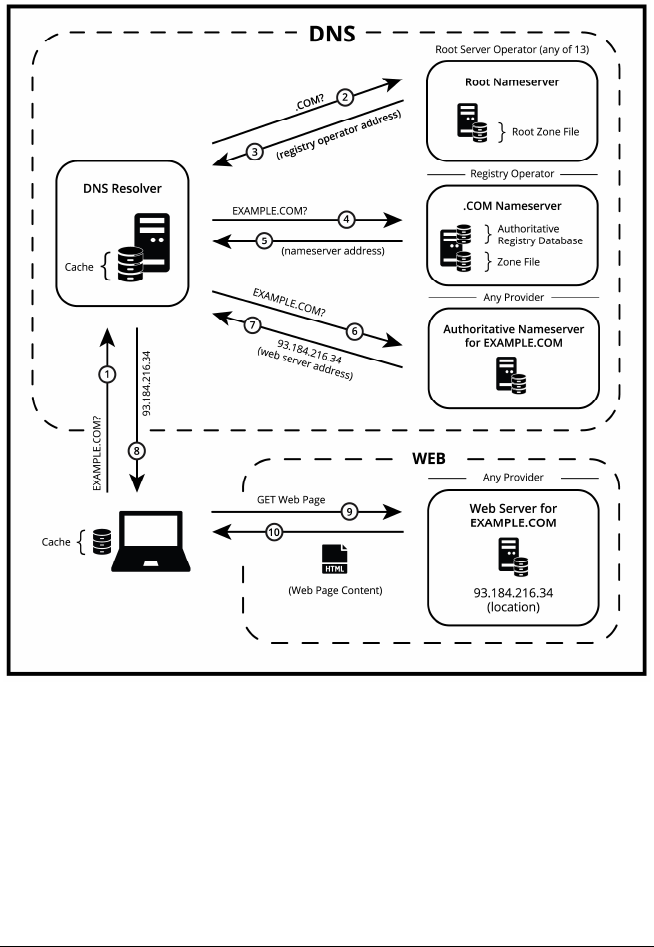

The following diagram illustrates these concepts in the context

of an actual DNS query.

26

Although all steps depicted in Fig. 1 are

relevant to how domain names are used to access web content, the

reader is directed to pay close attention to the description of Steps

4–5 and 9–10 which will prove central to certain arguments against

DNS censorship.

FIGURE 1

The process begins when a client needs to communicate with a

host but has only the host’s domain name. Although the client and

host may be any two computers on the Internet and the

communication may occur in the context of any type of Internet

activity, whether or not involving a human participant, for

purposes of this illustration, I use the familiar scenario in which an

26. The savvy DNS practitioner will observe that the process has been simplified

and that certain intermediate steps have been omitted for ease of discussion.

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 53

end user attempts to visit a website by typing a domain name—

here, EXAMPLE.COM—into his browser. The end user’s computer

first consults its local cache. Has the user visited EXAMPLE.COM

recently such that its IP address is already stored locally on the

computer? If not, the computer sends a DNS query to a DNS

Resolver (Step 1), which is typically provided by the user’s Internet

service provider but may be operated by any service provider or by

the user himself.

The DNS resolver then consults its own cache. Has the DNS

resolver received a DNS query for EXAMPLE.COM from another

user or computer recently such that its IP address is already cached

in memory? To illustrate the entire end-to-end flow, we will assume

that the cache in the DNS Resolver is empty

27

and that the full

DNS resolution process must play out. Without any information

about the requested name, the DNS Resolver looks first to the most

basic component of the domain name: its top-level domain (here,

.COM). To find a server that can provide authoritative information

about .COM names, the DNS Resolver sends its own query to a root

nameserver which is operated by an entity called a root server

operator (Step 2). The root server operator maintains an

authoritative “root zone file” that contains the name and IP address

of the registry operator for each top-level domain.

28

The root

nameserver responds to the query by sending back the IP address

for the .COM nameserver (Step 3).

Using the IP address returned by the root nameserver, the

DNS resolver sends a DNS query for EXAMPLE.COM to the .COM

nameserver (Step 4), which is operated by the .COM registry

operator. Just as a root server operator maintains an authoritative

root zone file containing information about all top-level domains in

the root (i.e., the Internet), the registry operator for a given top-

level domain maintains an authoritative zone file containing

information about all second-level domains (i.e., the “EXAMPLE”

in EXAMPLE.COM) in the top-level domain. Accordingly, in

response to the query from the DNS resolver, the .COM nameserver

checks the .COM zone file to see if a record exists for

EXAMPLE.COM. If so, it responds with the information in that

domain name record.

In theory, the DNS could have been designed so that the zone

file for a top-level domain stores the actual IP address for each

27. While the cache may be empty, a DNS resolver should nonetheless be pre-

programmed with the names and IP addresses of the thirteen root servers. Without this

a priori information, authoritative DNS resolution is not possible. DANIEL KARRENBERG,

THE INTERNET DOMAIN NAME SYSTEM EXPLAINED FOR NON-EXPERTS 4–5 (2017),

https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/The-Internet-Domain-

Name-System-Explained-for-Non-Experts-ENGLISH.pdf [https://perma.cc/76MQ-

3E9V].

28. NAT’L RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 22, at 96–97.

54 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

domain name in the top-level domain. For example, if the website

associated with EXAMPLE.COM is hosted at 93.184.216.34, the

.COM nameserver could just respond to DNS queries for

EXAMPLE.COM by returning that IP address. In practice,

however, rather than storing the actual IP address of the domain

name host, the zone file stores the IP address of a separate

computer called an authoritative nameserver. An authoritative

nameserver is a server that is ultimately responsible for providing

the IP address associated with a domain name. The domain name

owner can choose any available service provider to operate an

authoritative nameserver for his domain name or could even

operate the nameserver himself.

29

Thus, in this example, the .COM registry operator responds to

the query by returning the IP address of the authoritative

nameserver for EXAMPLE.COM (Step 5). Next, using the IP

address returned by the .COM registry operator, the DNS resolver

sends a DNS query to the authoritative nameserver for

EXAMPLE.COM (Step 6). At long last, the authoritative

nameserver responds with the actual IP address at which the

domain name is hosted (Step 7). At this point, the website address

is known. The DNS query, and the domain name associated with it,

can be said to have “resolved.” The DNS resolver updates its cache

and returns the IP address to the user’s computer (Step 8).

30

Finally, the user’s computer sends a request

31

for a web page to the

web server hosted at the IP address associated with the domain

name (Step 9), and the web server responds by sending the content

contained in the requested web page (Step 10). The user has, thus,

successfully accessed a website despite knowing only its domain

name mnemonic.

Two important observations can be gleaned from this

architecture. First, the process is inherently authoritative and

centralized.

32

A single, authoritative zone file exists for each top-

level domain, and a single entity—the registry operator—

29. The rationale for storing the IP address of an authoritative nameserver in the

zone file, rather than the IP address of the host, is that the domain name owner can

change the IP address of the host at any time by simply updating the authoritative

nameserver instead of requiring the registry operator to change the zone file. Otherwise,

in a sea of millions of domain names within a top-level domain with hosts constantly

shifting from one IP address to another, a registry operator would potentially need to

update the zone file for the top-level domain many times per second.

30. The user’s computer may also update its own cache to avoid the need to request

the IP address again until the time-to-live (specified in the DNS record returned by the

authoritative nameserver) expires.

31. In this case, a hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP) request.

32. Although the DNS is often rightly described as a decentralized system, it is

nonetheless centralized insofar as only one entity—the registry operator for the relevant

top-level domain—maintains the zone file for a given top-level domain and responds to

DNS queries for domain names within the zone file.

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 55

maintains that zone file and responds to queries for information

about any domain names within the top-level domain (Steps 4 and

5). If the registry operator fails to resolve queries for a given domain

name for any reason, Internet traffic that relies on the domain

name will function only for as long as the IP address of the domain

name host remains in cache somewhere in the DNS query chain

(typically, less than 24 hours).

33

Thereafter, any network

communications that rely on the domain name will fail. If the

domain name is associated with a website, the website will be

effectively inaccessible. Although the website will continue to be

reachable through its IP address, users who do not know that IP

address (the vast majority of users) will not be able to access the

website.

34

As explained infra,

35

it is this central control over the

DNS resolution process that provides registry operators with

unique control over the accessibility of website content and thus

makes DNS censorship possible.

Second, no content ever flows through the DNS itself, whether

website, email, video, chat, or other content.

36

The DNS exists only

to answer a simple question—what IP address is associated with a

given domain name? Once the requesting computer receives the

answer to that question, it communicates directly with the host

(using the IP address) through an Internet service provider and not

through any DNS servers. The servers involved in resolving a DNS

query (Steps 1-8) have no visibility into what the requesting

computer does with the returned IP address (Steps 9 and 10)—

much less the content provided by the host located at the address.

In this manner, the DNS has been analogized to a phonebook.

37

It

is used to look up numbers associated with the names of persons or

33. See Jeff Petters, What is DNS TTL + Best Practices, VARONIS: INSIDE OUT

SECURITY BLOG https://www.varonis.com/blog/dns-ttl/ [https://perma.cc/92L5-329R] (last

updated July 14, 2020) (calculating the average TTL value of the top 500 sites at 6,468

seconds or just under two hours).

34. See GlobalSantaFe Corp. v. Globalsantafe.com, 250 F. Supp. 2d 610, 620 n.31

(E.D. Va. 2003) (“[S]ince use of domain names is so ubiquitous, few if any users will know

the relevant IP address.”).

35. See infra Part II.A.

36. See Malcom et al., Fighting Neo-Nazis, supra note 13 (“Domain name companies

also have little claim to be publishers, or speakers in their own right, with respect to the

contents of websites. Like the suppliers of ink or electrical power to a pamphleteer, the

companies that sponsor domain name registrations have no direct connection to Internet

content. Domain name registrars have even less connection to speech than a conduit

provider such as an ISP, as the contents of a website or service never touch the registrar’s

systems.”).

37. See, e.g., XUEBIAO YUCHI, GUANGGANG GENG, ZHIWEI YAN & XIAODONG LEE,

CHINA INTERNET NETWORK INFORMATION CENTER, TOWARDS TACKLING PRIVACY

DISCLOSURE ISSUES IN DOMAIN NAME SERVICE 813 (describing the DNS as “the global

Internet’s phonebook”); Becky Hogge, The Great Phonebook in the Sky, NEW STATESMAN

(Feb. 7, 2008) https://www.newstatesman.com/scitech/2008/02/web-users-beards-

sandals-dns [https://perma.cc/8PF7-W8RV] (“Think of it as a great big telephone

directory in the sky.”).

56 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

organizations but plays no role in the activities performed by those

listed persons or organizations. As further described infra,

38

the

fact that web content is wholly external to the DNS provides one of

the strongest policy arguments against DNS censorship.

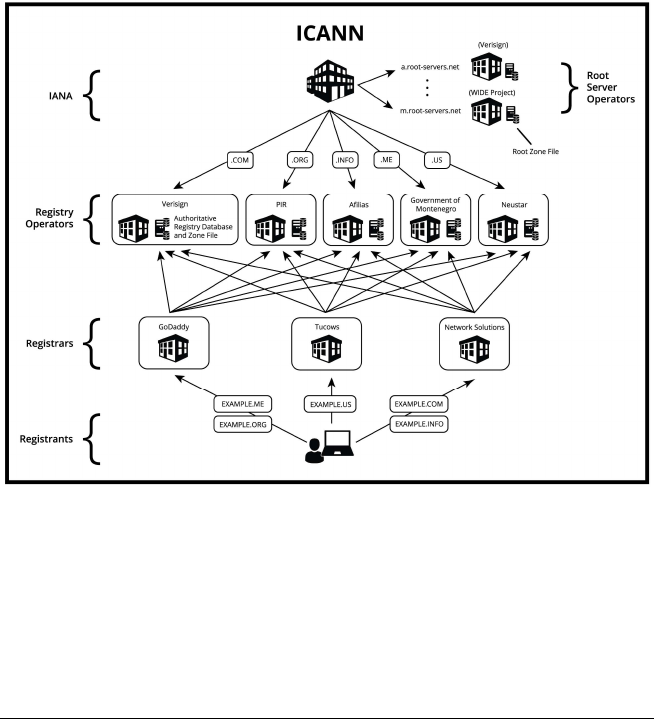

B. DNS Intermediaries

Entities that necessarily participate in the operation or

management of the DNS (for purposes of this article, “DNS

intermediaries”) generally fall into one or more of the following

categories: Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), root

server operators, registry operators, and registrars. The following

diagram depicts the relationship between the various DNS

intermediaries.

FIGURE 2

As depicted, each top-level domain is managed by a single

registry operator, be it a for-profit or non-profit corporation, a state-

controlled entity, or a government agency.

39

Although only five top-

level domains are depicted in Fig. 2, and only seven top-level

domains existed when the DNS was first implemented in 1985,

38. See infra Part II.B.

39. See NAT’L RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 22, at 129.

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 57

website operators may now choose from among 1,587 top-level

domains when registering a domain name.

40

The vast majority of

top-level domains (1,242 as of this article) are classified as generic

top-level domains (gTLDs)

41

meaning that any person or entity may

theoretically register a domain name within the TLD for any

purpose. Examples of gTLDs include the .COM, .ORG, and .NET

legacy TLDs as well as newer strings, such as .BOOK, .FUN, and

.XYZ. Set against these permissive gTLDs are generic-restricted

and certain sponsored top-level domains which limit registration to

certain classes of organizations or individuals.

42

Examples include

.BIZ (reserved for business entities), .EDU (accredited post-

secondary institutions), .JOBS (human resources managers), and

.XXX (adult entertainment). In some cases, a registry operator may

limit registration within a branded top-level domain (e.g., .BMW)

to itself and its affiliates—a “closed TLD.”

43

The remaining top-level domains

44

(315 as of this article) are

classified as country code top-level domains (ccTLDs),

predominantly two-character strings that map to a distinct country,

sovereign state, or dependent territory.

45

Examples include .US

(United States), .CN (China), and .NP (Nepal).

46

Country code top-

level domains are typically delegated to the government of the

country or territory to which they refer or to a private entity within

the country or territory,

47

although technical operations may be

outsourced to another entity, whether domestic or foreign.

48

40. See Root Zone Database, supra note 25 (listing each operational top-level

domain).

41. Id.

42. See NAT’L RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 22, at 114 (comparing the different

categories of generic top-level domains, including sponsored-restrictive, sponsored-

unrestrictive, unsponsored-restrictive, and unsponsored-unrestrictive).

43. See Paul Sawers, Google Domains Moves to a ‘.Google’ domain, VENTUREBEAT

(Mar. 30, 2016, 4:23 AM), https://venturebeat.com/2016/03/30/google-domains-dot-

google/ [https://perma.cc/6LTJ-UCGA].

44. In this explanation, I have excluded the remaining infrastructure and test

categories, which consist of fifteen top-level domains used only for technical and test

purposes and not in conjunction with any meaningful websites. See NAT’L RESEARCH

COUNCIL, supra note 22, at 114–20.

45. Id. at 113; JEFTOVIC, supra note 24, at 33–34.

46. Country Domains: A Comprehensive ccTLD List, IONOS,

https://www.ionos.com/digitalguide/domains/domain-extensions/cctlds-a-list-of-every-

country-domain/ [https://perma.cc/9VE7-Z8W6] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020).

47. NAT’L RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 22, at 10; Common Questions on

Delegating and Transferring Country-Code Top-Level Domains (ccTLDs), INTERNET

ASSIGNED NUMBERS AUTHORITY https://www.iana.org/help/cctld-delegation-answers

[https://perma.cc/93Q5-M9Q5] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (“For each ccTLD, at a

minimum both the manager and the administrative contact must be resident in the

country to which the domain is designated. This means they are accountable to the local

community and subject to local law.”).

48. For example, Verisign, a U.S. company, currently operates the .CC (Cocos

Island) and .TV (Tuvalu) ccTLDs on behalf of the local delegated managers. See Get

58 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

Country code top-level domain managers may set their own

policies concerning who may register domain names within their

top-level domains.

49

In some cases, a country will impose strict

registration criteria (e.g., .JP domain names are limited to

individuals and corporations located in Japan).

50

In other cases, a

country will allow any organization or individual to register within

its ccTLD, resulting in an additional class of de facto generic top-

level domains that may be popular because of their similarity to

English words or acronyms—e.g., .ME (Montenegro), .TV

(Tuvalu)—or because they can be used as “domain hacks” to spell

other words—e.g., INSTAGR.AM (Armenia), YOUTU.BE

(Belgium).

51

Although an entity may manage more than one top-level

domain, each top-level domain is delegated to only a single registry

operator.

52

As described supra, by vesting a single entity with the

responsibility of maintaining the authoritative zone file for a top-

level domain, the risk of naming collisions is effectively

eliminated.

53

The registry operator not only maintains the zone file

for its top-level domain but also operates the nameserver for the

top-level domain, responding to DNS queries for domain names

registered therein (Steps 4 and 5 in Fig. 1).

In addition to the zone file, the registry operator maintains an

authoritative registry database for the top-level domain. The

registry database lists authoritative information about each

Creative With A .cc Domain Name, VERISIGN, https://www.verisign.com/en_US/domain-

names/cc-domain-names/index.xhtml [https://perma.cc/8P8N-YLCK] (last visited Oct.

18, 2020); A .tv Domain Name Is Where the World Turns for Entertainment, VERISIGN,

https://www.verisign.com/

en_US/domain-names/tv-domain-names/index.xhtml [https://perma.cc/4KB9-TW98]

(last visited Oct. 18, 2020).

49. See About ccTLD Compliance, ICANN,

https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/cctld-2012-02-25-en [https://perma.cc/M38H-

4CE4] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (“The ccTLD policies regarding registration,

accreditation of registrars and Whois are managed according to the relevant oversight

and governance mechanisms within the country, with no role for ICANN’s Compliance

department in these areas.”).

50. About .jp domains, GODADDY, https://www.godaddy.com/help/about-jp-

domains-20219 [https://perma.cc/Q5HY-726G] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020); see also About

ccTLDs (Country-Code Domain Names), GODADDY

https://www.godaddy.com/help/about-cctlds-country-code-domain-names-6243

[https://perma.cc/HK7K-GTJN] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (providing specific

requirements and considerations for various ccTLDs).

51. See NAT’L RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 22, at 116–17 (noting that the

distinction between generic top-level domains and country code top-level domains has

significantly eroded).

52. Id. at 129 (“There is always one, and only one, registry for a given TLD, but, as

noted above, an organization can be the registry operator for more than one TLD.”). For

example, Binky Moon, LLC d/b/a “Donuts” manages nearly 200 different top-level

domains, including .COMPANY, .GIFTS, and .TOYS. See also Root Zone Database, supra

note 25.

53. See supra Part I.A.

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 59

domain name that has been registered within the top-level domain

including, typically, the name and contact information of the person

or business who registered the domain name, the registration

creation and expiration date, and the domain status.

54

Whereas the

zone file maintained by the registry operator functions like a

phonebook, listing addresses associated with names. The registry

database can best be analogized to a land registry maintained by a

county title office or similar administrator. Because only one entity

can be listed as the holder of a domain name, the registry database,

which is publicly accessible through a WHOIS service, operated by

registrars and registry operators, serves to put the world on notice

of which parties claim exclusive rights to which domain names.

55

Registering a domain name, therefore, is fundamentally a matter

of recording a person’s or organization’s interest in the domain

name within the authoritative registry database for the associated

top-level domain. As we’ll see,

56

the distinction between recordation

in the authoritative registry database and the answering of DNS

queries from the zone file will prove important when it comes to

separating the property status of domain names from certain

domain-related services provided by DNS intermediaries.

Although registry operators maintain the authoritative

registry databases for the top-level domains they manage, they

typically do not offer domain name registration services directly to

the public, at least for generic top-level domains.

57

Instead, when a

person wishes to register a domain name, he engages the services

of a domain name registrar, in most cases, through the registrar’s

self-service online registration system. For example, and as

depicted in Fig. 2, a customer who wishes to register the domain

name EXAMPLE.INFO might visit the website of a registrar, such

54. Registry Agreement: Appendix C, ICANN, §§ C2.1, C5, (June 6, 2003)

https://www.icann.org/resources/unthemed-pages/registry-agmt-appc-redlined-2003-06-

06-en [https://perma.cc/6Q8Q-E5CP] (“[T]he registry database [is] the authoritative

source of domain names and their associated hosts (name servers).”); GlobalSantaFe

Corp., v. Globalsantafe.com, 250 F. Supp. 2d 610, 619 (E.D. Va. 2003) (“The registry . . .

maintain[s] and operat[es] the unified Registry Database, which contains all domain

names registered by all registrants and registrars in a given top level domain . . . .”).

55. See About WHOIS, ICANN https://whois.icann.org/en/about-whois

[https://perma.cc/XCU4-A5GG] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020). Although the .COM and .NET

legacy gTLDs operate in a “thin registry” model in which information about the registrar,

rather than the registrant, is stored in the registry database, information about the

registrant is nonetheless accessible through the WHOIS service, which queries both the

registry operator’s and the registrar’s databases to identify the end registrant. See What

Are Thick and Thin Entries?, ICANN, https://whois.icann.org/en/what-are-thick-and-

thin-entries [https://perma.cc/CJE8-NPQG] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020). In any event, an

effort is under way to convert .COM and .NET to “thick registries.” Thick WHOIS,

ICANN (May 7, 2019), https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/thick-whois-2016-06-27-

en [https://perma.cc/F3P2-QJXE].

56. See infra Part III.D.3.

57. See NAT’L RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 22, at 135–37 (chronicling the

development of separate registry and registrar functions and entities).

60 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

as Network Solutions, Inc. The registrar then queries the

authoritative registry database maintained by the registry operator

responsible for the .INFO top-level domain (currently, Afilias Ltd.)

to determine whether the domain name is available. If so, the

customer pays the registrar-prescribed fee (the “registration fee”),

58

the registrar transmits the customer’s information to the registry

operator, and the registry operator creates a record in the registry

database associating the domain name with the customer

information so provided. At this point, the customer becomes the

sole holder of the domain name and is deemed the “registrant.” In

addition, if the registrant wishes to make the domain name

operational, he provides the registrar with the name and address of

authoritative nameservers for his domain name, which the

registrar forwards to the registry operator and the registry operator

records in the zone file.

Registrars typically contract with multiple registry operators

in order to be able to offer domain names across multiple top-level

domains. Registry operators are likewise required to allow any

accredited registrar to sell domain names within their top-level

domains.

59

As a result, a customer who desires to register a domain

name may choose from among thousands of different registrars.

60

Moreover, after registering a domain name through one registrar,

a registrant may later transfer his registration to another

registrar.

61

Domain names may be registered in one-year increments, up

to a maximum registration term of ten years.

62

At any time during

the registration term, a registrant may renew his registration by

paying the prescribed renewal fee for a renewal term of one to ten

years, provided that the total remaining registration term does not

exceed ten years. In this manner, a registrant can maintain

exclusive rights to his domain name indefinitely as long as he

58. As of this article, registration fees generally range from $2 to $20. Maxym

Martineau, How much does a domain name cost?, GODADDY (July, 8, 2019),

https://www.godaddy.com/garage/how-much-domain-name-cost/ [https://perma.cc/FR8J-

Z8P8].

59. See NAT’L RESEARCH COUNCIL, supra note 22, at 136 (“Under the terms of their

agreements with ICANN, gTLD registries are required to permit registrars to provide

Internet domain name registration services within their top-level domains.”).

60. See generally ICANN, DESCRIPTIONS AND CONTACT INFORMATION FOR ICANN-

ACCREDITED REGISTRARS, https://www.icann.org/registrar-reports/accredited-list.html

[https://perma.cc/3N6P-AQQA] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020).

61. See Transfer Policy, ICANN (June 1, 2016),

https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/transfer-policy-2016-06-01-en

[https://perma.cc/X336-8GHH] (providing registrants with the general right to transfer

domain names between registrars).

62. FAQs, ICANN https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/faqs-2014-01-21-en

[https://perma.cc/7RJY-D4UZ] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (“Each registrar has the

flexibility to offer initial and renewal [registrations] in one-year increments, provided

that the maximum remaining unexpired term shall not exceed ten years.”).

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 61

continues to renew the domain and pay the required renewal fees

before his current registration term expires. If a registrant fails to

renew his domain name before the registration term expires, a

series of grace periods apply during which he may still renew the

name subject to additional fees.

63

Once all grace periods have been

exhausted, the registration is deleted, the domain name reverts to

unregistered status, and any customer may register the name on a

first-come basis.

64

Importantly, upon expiration, control of the domain name

reverts back to the registry operator and not to the registrar whom

the registrant used to register the name.

65

Accordingly, just as

when the domain name was originally registered, a new registrant

may register it through any accredited registrar.

66

The original

registrar can lay no greater claim to the domain name than any

other registrar. If the registrar wishes to possess the now-expired

domain name for its own purposes, it must register the domain

name just like any other customer. And, despite knowing when an

un-renewed domain name will expire, even the original registrar

may not be the favorite to win the registration race. “Drop-

catchers,” a special class of professional domain name investors

(“domainers”), employ sophisticated, automated systems to monitor

high-value domain names that are scheduled for expiration and

attempt to register them before any other entity.

67

As a result,

valuable domain names are often snatched up by drop-catchers

within seconds of their expiration.

68

As will be shown,

69

limited

registration periods and control over expired domain names will

prove relevant to the issue of which party may claim title to

registered domain names.

Atop this organizational scheme sits the IANA. By itself, IANA

is not an entity but a function (or set of functions), and the entity

63. JEFTOVIC, supra note 24, at 22–26.

64. Id. at 25–26.

65. See id. (explaining that final expiration of a domain name registration will result

in deletion of the registration record from the authoritative registry database, which

record would include any authoritative association between the domain name and the

sponsoring registrar).

66. See AGP Limits Policy and Draft Implementation Plan, ICANN,

https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/agp-draft-2008-10-20-en [https://perma.cc/UZ9Q-

MHZD] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (“Once a domain name is deleted by the registry at

this stage, it is immediately available for registration by any registrant through any

registrar.”).

67. See generally NAJMEH MIRAMIRKHANI, TIMOTHY BARRON, MICHAEL FERDMAN &

NICK NIKIFORAKIS, PANNING FOR GOLD.COM: UNDERSTANDING THE DYNAMICS OF

DOMAIN DROPCATCHING, 2018 IW3C2 (INTERNATIONAL WORLD WIDE WEB CONFERENCE

COMMITTEE, 2018).

68. See JEFTOVIC, supra note 24, at 25 (“If the [expired] domain has any marginal

value . . ., then the ‘drop-catchers’ will now converge and the domain will be reregistered

within a few milliseconds.”).

69. See infra Part III.E.3.

62 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

who performs the IANA function is responsible for coordinating the

delegation of top-level domains and the allocation of IP addresses.

70

Since 2000, ICANN, a non-profit corporation headquartered in

California, has performed the IANA function.

71

But prior to 2000,

the function was performed by universities and, in its earliest

incarnation, by a single individual, John Postel.

72

In performing the

IANA function, ICANN is responsible for delegating each top-level

domain to a registry operator, which it does pursuant to registry

agreements typically lasting ten years.

73

Absent breach, a registry

agreement may automatically renew for an additional ten-year

period.

74

However, such a presumptive right to renewal was not

always guaranteed to registry operators. Early registry

agreements, such as ICANN’s delegation of .COM to VeriSign and

.ORG to Network Solutions, provided no presumptive right to

renewal. And ICANN was free to re-delegate such top-level domains

to other parties upon expiration of the registry agreements.

75

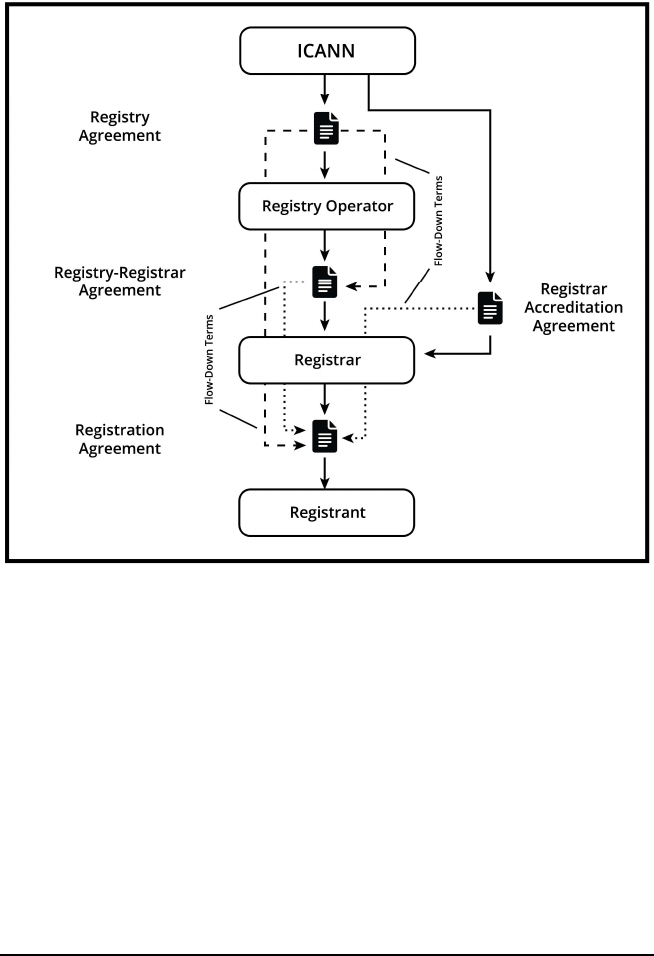

In addition to setting policy for the DNS through a global

stakeholder process, the IANA function vests ICANN with

responsibility for allocating IP address blocks to network operators

around the world.

76

ICANN also oversees the Root Server System,

a set of thirteen different root zone servers (lettered ‘a’ through ‘m’),

each of which hosts a copy of the root zone file and responds to DNS

queries for the IP addresses of top-level domain nameservers (Steps

2 and 3 of Fig. 1).

77

Notably, among these four categories of DNS intermediaries,

only registry operators and root server operators necessarily

70. See About Us, INTERNET ASSIGNED NUMBERS AUTHORITY,

https://www.iana.org/about [https://perma.cc/SF57-YZY2] (last visited Oct. 18, 2019)

(describing the IANA functions).

71. JOEL SNYDER, KONSTANTINOS KOMAITIS & ANDREI ROBACHEVSKY, THE HISTORY

OF IANA: AN EXTENDED TIMELINE WITH CITATIONS AND COMMENTARY, INTERNET

SOCIETY 5 (Jan. 2017), https://www.internetsociety.org/wp-

content/uploads/2016/05/IANA_Timeline_20170117.pdf [https://perma.cc/EM4E-UB36].

72. Id. at 2–5.

73. Base Registry Agreement, ICANN, § 4.1

https://newgtlds.icann.org/sites/default/files/agreements/agreement-approved-09jan14-

en.htm [https://perma.cc/9T4W-4W8V] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) [hereinafter Base

Registry Agreement, ICANN].

74. Id. at § 4.2.

75. See ICANN-NSI Registry Agreement, ICANN, § 23 (Sept. 28, 1999),

https://archive.icann.org/en/nsi/nsi-registry-agreement.htm [https://perma.cc/B42W-

FCTK] (providing no presumptive right to renewal after eight years); See also .org

Registry Agreement, ICANN, § 5.1 (May 25, 2001),

https://www.icann.org/resources/unthemed-pages/registry-agmt-org-2001-05-25-en

[https://perma.cc/Z5BA-27EP].

76. See Number Resources, INTERNET ASSIGNED NUMBERS AUTHORITY,

https://www.iana.org/numbers [https://perma.cc/3A3C-ANWV] (last visited Oct. 18,

2020).

77. See Root Servers, INTERNET ASSIGNED NUMBERS AUTHORITY,

https://www.iana.org/domains/root/servers [https://perma.cc/8XQC-F2GK] (last visited

Oct. 18, 2020).

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 63

participate in the resolution of domain names. As depicted in Fig.

1, when a query is made to resolve a domain name, in the absence

of any temporarily cached information, the query is ultimately

routed to a root server operator, then to the registry operator, and

then to an authoritative nameserver for the domain name. Because

it is impossible, under the current configuration of the DNS, for an

un-cached DNS query to resolve if these functions are not

performed, I refer to them as “core DNS services.”

By contrast, at no point is it necessary for the registrar or

ICANN to participate in the resolution of any domain name.

Instead, the registrar’s role is largely limited to registering and

renewing domain names on the registrant’s behalf, sending

reminders when the domain name is approaching expiration (if

applicable), and allowing the registrant to update aspects of the

registration, such as contact information, nameserver delegation,

and security parameters.

78

Registrars perform most or all of these

functions through the registry operator’s automated system.

79

In

any event, none of these functions must be performed on a

continual, real-time basis for a domain name to remain operational.

Because registrars play no part in resolving DNS queries for

domain names, I refer to the administrative services they provide

as “non-core DNS services.”

To be sure, registrars frequently offer value-added services

when customers register domain names, such as website hosting,

email, or WHOIS privacy.

80

Indeed, such value-added services may

provide the bulk of a registrar’s net income, given the low profit

margins involved in simply marking up domain name registration

and renewal fees. And frequently, one such value-added service

that a registrar offers when a customer registers a domain name is

to allow the registrant to use the registrar’s authoritative

nameservers to resolve DNS queries for the domain name (Steps 6

and 7 in Fig. 1).

81

While authoritative name resolution is a core

DNS service, a registrant is free to choose any available provider to

operate authoritative nameservers for his domain and may even

perform the function himself. Thus, after registering a domain

78. JEFTOVIC, supra note 24, at 37.

79. GlobalSantaFe Corp. v. Globalsantafe.com, 250 F. Supp. 2d 610, 619–20 (E.D.

Va. 2003).

80. Domain Name Industry, ICANN,

https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/domain-name-industry-2017-06-20-en

[https://perma.cc/BW56-DAPR] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (“Many registrars also offer

other services such as web hosting, privacy/proxy, website builder, etc.”).

81. See How Do I Find The DNS Provider Of My Domain?, INTERMEDIA,

https://kb.intermedia.net/article/1347 [https://perma.cc/7ASV-3FPT] (last visited Oct.

18, 2020) (explaining that DNS hosting for a domain name is commonly provided by the

domain name registrar).

64 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

name, the services of the sponsoring registrar are not strictly

necessary for the name to remain operational.

Likewise, as the performer of the IANA function, ICANN’s role

is to set technical policy for the DNS, not to operate it.

82

Although

ICANN delegates responsibility for managing top-level domains to

registry operators, ICANN itself neither manages any top-level

domain nor operates any top-level domain nameserver. And

although ICANN operates one of the thirteen root zone servers, it

does so only as one of thirteen mirrors and, thus, is not essential to

the resolution of any DNS query. This distinction between core and

non-core DNS services will become important when it comes to

analyzing whether a given DNS intermediary should be able to

suspend, cancel, or transfer a domain name in the course of

terminating its relationship with a registrant.

II. DNS INTERMEDIARY POWER OVER CONTENT

DNS intermediaries lack direct control over Internet content.

At any time, a user may visit a website by simply typing the IP

address of a provider’s web server into her browser and

downloading the content provided by that server (Steps 9 and 10 of

Fig. 1). These steps are wholly external to the DNS, and so

registrars, registry operators, and even ICANN are powerless to

interfere. But because IP addresses are not only difficult to

remember but also constantly changing, DNS intermediaries can

exert de facto control over website content through their control

over the registration and resolution of domain names. In this part,

I trace the history of that control, as intermediaries first tailored

their agreements to prevent the DNS from becoming a tool of

trademark infringement, then to disrupt criminality, and finally to

police offensive, but legal, content.

A. Cybersquatting and Restrictions Against Illegal Content

In the early days of the DNS, domain names came with few, if

any, strings attached. Even as late as 1994, one could register a

domain name by simply emailing a request to Network Solutions, a

private corporation under contract with the National Science

Foundation (NSF) to manage several legacy top-level domains,

including .COM and .ORG.

83

No registration fee was required and

82. See Bridy, Notice and Takedown, supra note 15, at 1361 (describing ICANN’s

“narrow technical mandate”).

83. See Kremen v. Cohen, 337 F.3d 1024, 1026 (9th Cir. 2003) (describing the

process by which Sex.com was registered in 1994). See also NAT’L RESEARCH COUNCIL,

supra note 22, at 75–78 (explaining the contractual framework under which Network

Solutions managed domain name registrations on behalf of NSF).

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 65

no contract governed the registration.

84

By the end of 1995,

however, Network Solutions was receiving more than 20,000

registration requests per month—taxing its limited, NSF-funded

resources and resulting in a five-week delay to register any name.

85

As a result, on September 14, 1995, the NSF authorized Network

Solutions to begin charging a $50 fee to register new domain names

and to retain such registration fees to offset operational costs.

86

Formal terms and conditions soon followed in the form of

registration agreements that customers were required to accept in

order to register domain names.

Early registration agreements were relatively simple,

requiring the registrant to do little more than pay the required

registration fee, provide accurate contact information, and submit

to the registrar’s dispute resolution policy.

87

Dispute policies

empowered registrars to resolve disputes between registrants and

trademark holders over registered domain names

88

and reflected

the fact that trademark infringement was the predominant legal

concern in the DNS at the time. That concern stemmed from the

fact that initially, nothing stopped an individual from registering

almost any available string as a domain name, even if the string

consisted of a trademarked word or phrase in which the registrant

possessed no rights. Coupled with the absence of registration fees

before 1995, this lax registration environment gave rise to the

practice of deliberately registering a company’s name or trademark

in hopes of selling the domain name at a high price once the less

tech-savvy company belatedly realized the importance of

establishing a presence in cyberspace. Famous early examples

include disputes over McDonalds.com, MTV.COM, and Peta.org.

89

This problem, colloquially termed “cybersquatting,” was

originally left to registrars to resolve under the terms of their

84. See Kremen, 337 F.3d at 1026–28; Caroline Bricteux, Regulating Online Content

through the Internet Architecture: The Case of ICANN’s New gTLDs, 7 J. INTELL. PROP.

INFO. TECH. ELECTRONIC & COMM. L. 229, 232 (2016) (“At that time, registration of a

SLD was subsidized by the NSF and free of charge for the end user.”) [hereinafter

Bricteux, ICANN’s New gTLDs].

85. The Internet Grows Up, NSF (Sept. 14, 1995),

http://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=100806 [https://perma.cc/DF78-

5WR4].

86. Id.; Michael Brian Pope et al., The Domain Name System: Past, Present, and

Future, 30 COMM. ASS’N FOR INFO. SYS. 329, 332 (2012).

87. See, e.g., NSI Solutions Service Agreement Version Number 2.0, NETWORK

SOLUTIONS (Dec. 2, 1998), http://web.archive.org/web/19981203102059/http://network

solutions.com/agreement_print.html [https://perma.cc/WT7X-DZMU].

88. See, e.g., Network Solutions’ Domain Name Dispute Policy, NETWORK

SOLUTIONS (Feb. 25, 1998),

https://web.archive.org/web/19981202103009/http://www.networksolutions.com/dispute

-rev03.html [https://perma.cc/G3SY-2QBU].

89. Matt Novak, 5 Domain Name Battles of the Early Web, GIZMODO (Nov. 21, 2014,

1:50 PM), https://paleofuture.gizmodo.com/5-domain-name-battles-of-the-early-web-

1660616980 [https://perma.cc/88XZ-B7YM].

66 COLO. TECH. L.J. [Vol. 19.1

registration agreements. But by 1999, after significant pressure

from trademark owners, Congress enacted the Anticybersquatting

Consumer Protection Act (ACPA) to provide a uniform federal

framework for resolving cybersquatting disputes.

90

Under the

ACPA, a person may be liable in a federal civil action by a

trademark owner if that person registers, traffics in, or uses a

domain name that is identical or confusingly similar to the

trademark with bad faith intent to profit from the trademark.

91

If

a court finds for the trademark owner in an ACPA action, the court

may order the forfeiture or cancellation of the domain name or

transfer the domain name to the trademark owner.

92

Moreover, to

deal with the problem of cybersquatters located abroad, the ACPA

provides for in rem jurisdiction over the disputed domain name by

deeming its situs to be in the judicial district in which the domain

name registrar, registry operator, or other relevant DNS

intermediary is located.

93

Likewise, shortly after ICANN assumed the mantle of the

IANA, ICANN followed suit with its own procedure for dealing with

trademark disputes—the Uniform Domain Name Dispute

Resolution Policy (UDRP).

94

Like the ACPA, the UDRP provides a

mechanism for trademark holders to challenge the bad faith

registration and use of domain names that implicate registered

trademarks.

95

Unlike the ACPA, however, which requires the

trademark holder to file suit in federal court, the UDRP establishes

a lightweight, alternative dispute resolution framework that

provides for fast and inexpensive adjudication of cybersquatting

claims. Complainants may select from ICANN-accredited

arbitrators, such as the World Intellectual Property Organization

(WIPO), the National Arbitration Forum (NAF), or, previously,

certain for-profit companies.

96

If a complainant prevails, the only

90. See Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2000, Pub. L. No. 106–113, 113 Stat. 1501

(1999) (codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1125(d)(1)(A)(i)-(ii)).

91. 15 U.S.C. § 1125(d)(1)(A) (2018).

92. Id. at § 1125(d)(1)(C).

93. Id. at § 1125(d)(2)(C); see, e.g., GlobalSantaFe Corp. v. Globalsantafe.com, 250

F. Supp. 2d 610, 610 (E.D. Va. 2003) (permitting a trademark holder to take down an

infringing domain name under the ACPA registered in South Korea, where the

registrant could not be served with process and the Korean registrar had been enjoined

by a Korean court from canceling the domain name).

94. See Timeline for the Formulation and Implementation of the Uniform Domain-

Name Dispute-Resolution Policy, ICANN,

https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/schedule-2012-02-25-en [https://perma.cc/VZ3X-

5FBY] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020).

95. See Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy, ICANN,

https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/help/dndr/udrp-en [https://perma.cc/56KB-

NYPH] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020).

96. See List of Approved Dispute Resolution Service Providers, ICANN,

https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/providers-6d-2012-02-25-en

[https://perma.cc/6N8L-X9EY] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020).

2021] MASTERS OF THEIR OWN DOMAINS 67

available remedies are cancelation or transfer of the subject domain

name.

97

However, a losing registrant may stay either remedy by

challenging the decision in a court of competent jurisdiction within

ten days of the ruling.

98

Although both the ACPA and the UDRP provide a forum for IP

infringement claims to be made against domain name registrants,

such infringement claims are limited to trademark disputes.

Moreover, a trademark claim against a domain name registrant can

be stated under the ACPA or UDRP only to the extent it alleges

that the domain name itself infringes the complainant’s

trademark.

99

Neither framework provides a cause of action against

a registrant based on the content of any website associated with the

domain. Thus, actions may not be brought under the ACPA or the

UDRP against the operator of a website selling counterfeit

merchandise, such as fake Gucci bags or Rolex watches, if the

trademark owners’ claims go to the content or operation of the

website rather than the domain name used to host the website.

Likewise, movie and music rights holders could not look to the

ACPA or UDRP to take down a domain name associated with a

website hosting pirated movies and music if the dispute concerns

only copyright infringement.

Over time, registrars added restrictions to their agreements

concerning how registrants may use domain names in the form of

“acceptable use policies” that went beyond cybersquatting.

Registrars introduced prohibitions on malicious cyber activity

(spamming, phishing, and distributing malware),

100

IP piracy

(copyrighted movie, music, and software sharing),

101

and other

types of illegal activity (child pornography, online gambling, and

money laundering).

102

While registrars might be commended for

seeking to curb illegal activity, such restrictions marked a

fundamental expansion of registrar authority into new territory:

97. Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy, ICANN, § 4(i) (Oct. 24, 1999),

https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/policy-2012-02-25-en [https://perma.cc/NNM4-

FS6Q].

98. Id. at § 4(k).

99. See Bridy, Notice and Takedown, supra note 15, at 1356 (“Trademark cases that

do not involve cybersquatting cannot be adjudicated via the UDRP . . . .”); Adam

Silberlight, Domain Name Disputes Under the ACPA in the New Millennium: When is

Bad Faith Intent to Profit Really Bad Faith and Has Anything Changed with the ACPA’s

Inception?, 13 FORDHAM INTELL. PROP. MEDIA & ENT. L.J. 269, 277 (2002) (“Although it

is based on traditional trademark principles, the ACPA is narrowly tailored to deal with

problems arising from domain name disputes.”).

100. See, e.g., Registration Agreement, ENOM, § 4(d)(ii),

https://www.enom.com/terms/agreement.aspx [https://perma.cc/22NC-33WW] (last

visited Oct. 18, 2020).

101. See, e.g., MyDomain’s Acceptable Use Policy (AUP), MYDOMAIN, § 1(a)(x),