www.afnic.fr | [email protected]

Twitter: @AFNIC | Facebook: afnic.fr

The Global

Domain Name

Market in 2021

Afnic Studies

June 2022

2

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

CONTENTS

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4

2. Executive summary ............................................................................................... 6

3. Global trends ............................................................................................................. 10

3.1. A return to normality? ...................................................................................................... 10

3.2. Persistently contrasting performances ................................................................ 11

3.3. nTLDs: surface tumult and baseline development ...................................... 12

3.4. Strengthening of .COM positions in 2021 as in 2020 ...................................... 13

4. Legacy TLDs in 2021 ................................................................................................ 15

4.1. The .COM domain versus Other Legacy TLDs: persistently

contrasting situations ..................................................................................................... 16

4.2. Legacy TLD creations during the post-COVID phase .................................. 16

4.3. Retention rates up sometimes significantly .................................................... 18

4.4. Implications in terms of naming strategies .................................................... 20

5. ccTLDs (country-code Top-Level Domains) ...................................... 22

5.1. ccTLD creations during the post-COVID phase ............................................. 22

5.2. The regional dynamics of ccTLDs ........................................................................... 23

5.3. Weight of quasi-TLDs and Penny ccTLDs ............................................................ 27

6. nTLDs .............................................................................................................................. 30

6.1. Global change in the stock of “new TLDs” .......................................................... 30

6.2. Definition of “new TLD” “segments” ......................................................................... 31

6.3. Performance of “new TLD” “segments” ................................................................ 33

6.4. Distribution of new TLDs in volumes of domain name

registrations .......................................................................................................................... 35

6.5. Change in retention rates per segment ............................................................. 39

6.6. The “Penny nTLD” phenomenon ............................................................................... 40

6.6.1. Retention Rate ....................................................................................................................... 41

6.6.2. Creation Rate ........................................................................................................................ 43

6.6.3. Identification of Penny nTLDs in 2021 ..................................................................... 43

6.7. Reflections on the business models of the nTLDs ......................................... 47

6.7.1. Unequal business models ............................................................................................ 48

6.7.2. The consequences in terms of marketing strategies ............................... 50

6.7.3. Exclusive TLDs vs. mass TLDs ...................................................................................... 50

6.7.4. Bad pricing never pays ................................................................................................... 51

6.7.5. Rights holders and domainers, two false friends .......................................... 51

6.7.6. Convincing investors ....................................................................................................... 51

6.7.7. Success or failure is linked not to volume but to the pertinence of

the strategy with respect to market conditions. .......................................... 52

6.8. “Leaders” still fragile ......................................................................................................... 52

3

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

6.9. Market share of the main back-end registry operators.......................... 55

7. The distribution of domain names in the world at year-end

2021 ............................................................................................................................. 58

7.1. Overview .................................................................................................................................. 58

7.2. Weight of segments in Africa .................................................................................... 59

7.3. Weight of segments in Latin America .................................................................. 59

7.4. Weight of segments in Asia-Pacific ....................................................................... 61

7.5. Weight of segments in Europe .................................................................................. 62

7.6. Weight of segments in North America ................................................................ 63

7.7. Summary tables ................................................................................................................. 64

7.8. Topology of ICANN registrars ..................................................................................... 65

7.9. Lessons learned ...................................................................................................................73

8. Highlights of 2021 and early 2022 ............................................................... 75

8.1. A TLD market that is still active ................................................................................. 75

8.1.1. Changes in registries ...................................................................................................... 75

8.1.2. Back-end operators ......................................................................................................... 76

8.2. Mergers and acquisitions: continuous consolidation, accompanied

by financiers .......................................................................................................................... 77

8.3. New services ......................................................................................................................... 78

8.3.1. Data, Security and Monitoring .................................................................................. 78

8.3.2. Innovations brought to market or in preparation ....................................... 79

8.3.3. Infrastructures ..................................................................................................................... 79

9. Conclusions and outlooks .............................................................................. 80

4

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

1. Introduction

The publication of ICANN statistics as at 31/12/2021 allows a quantified assessment of 2021, a

period marked by the post-COVID-19 situation.

The data on which this study is based come from ICANN reports (Transactions - registries),

from information provided by registries in certain frameworks such as the Council of

European National Top-Level Domain Registries (CENTR) or the Asia-Pacific Top-Level

Domain Association (APTLD) or via their websites, and research conducted by Afnic. In some

cases, we have also relied on specialised sites such as https://ntldstats.com.

Our figures may vary slightly from those reported by other sources, in particular due to the

lack of precise data for certain country code Top-Level Domains (ccTLDs).

A supplement to the annual review of the market for domain names in

France

This study supplements our Annual review of the French domain name market published at

the beginning of each year. It helps put into perspective the specific trends of the French

market by comparing local data with global data.

By way of reminder:

growth of the French market as a whole was 3.6% in 2021 compared with 6.2% in 2020 (for

the .FR TLD the respective figures were 5.8% and 6.2%);

the market shares of the various segments in France were, at the end of 2021, 39% for .FR,

45% for .COM, 11% for “Other Legacy” TLDs, 3% for French-owned foreign ccTLDs and 2% for

“new TLDs”.

We refer the reader to this document for more information on the French market. It can be

downloaded free of charge from the Afnic website:

In French:

https://www.afnic.fr/wp-media/uploads/2022/03/Le-.FR-en-2021.pdf

In English:

https://www.afnic.fr/wp-media/uploads/2022/03/The-.FR-in-2021.pdf

5

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

Definitions

APTLD: Asia Pacific Top-Level Domain Association.

CENTR: Council of European National Top-Level Domain Registries

ICANN: Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers.

TLD (Top-Level Domain): a domain at the highest level in the hierarchical Domain Name

System of the Internet after the root domain. .FR and .ORG are top-level domains.

ccTLD (country-code Top-Level Domain): top-level domain corresponding to a territory or

country. The ccTLD for France is .FR, but there are other French ccTLDs such as .RE (Réunion),

.PM (Saint Pierre and Miquelon), etc.

gTLD (generic Top-Level Domain): a generic TLD, not attached to a particular country or

territory. .COM, .NET and .ORG are gTLDs.

Legacy gTLD: a generic TLD created before 2014. These are “legacy” TLDs, such as .COM, .NET,

.ORG or more recently (2001-2004) .INFO, .BIZ, .MOBI, etc.

nTLD (new Top-Level Domain): generic TLD created after 2014. nTLDs are divided into several

sub-segments such as geoTLDs (regions, cities, etc.), community TLDs (community-based),

.brand (TLDs corresponding to major brands) or generic nTLDs (common dictionary terms).

Penny TLD: TLD that is free or sold at a very low price and/or with a very high creation rate

combined with a very low renewal rate.

Annualised creation rate: total number of create operations over the last 12 months/stock

end of period

Annualised retention rate: (Stock end of period – creations over the last 12 months) / Stock

start of period (12 months earlier)

6

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

2. Executive summary

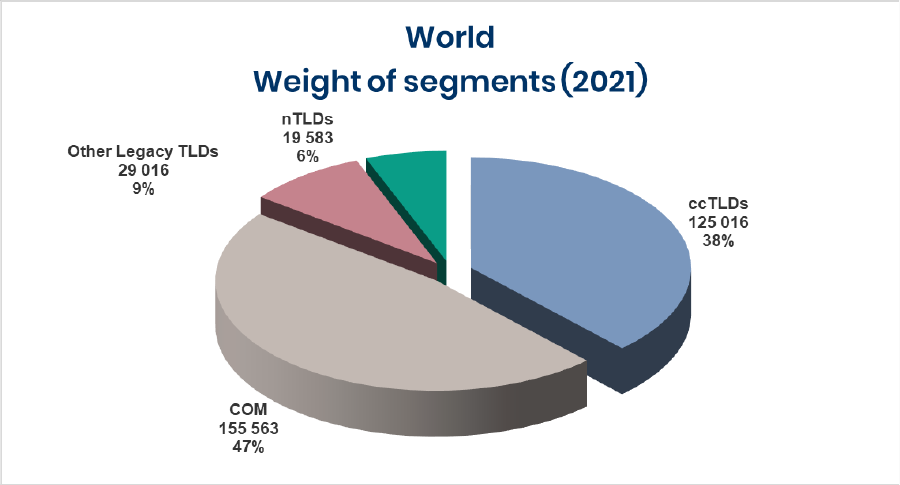

At the end of 2021, the global domain name market represented some 352 million

domain names, including:

• 164 million .COM names;

• 32 million “Other Legacy TLD” names (.NET, .ORG, .BIZ, .INFO, etc.);

• 29 million “new TLD” names created from 2014 onwards;

• 125 million names under ccTLDs (so-called “geographic” domains).

2021 saw the domain name market grow by 0.9%, compared with 1.3% in 2020 and 4.7% in 2019.

This performance is misleading however, as it was due to a very small number of TLDs

posting very significant changes.

nTLDs taken as a whole lost 9% of their stock, against a 1% fall in 2020 and 19% growth in 2019.

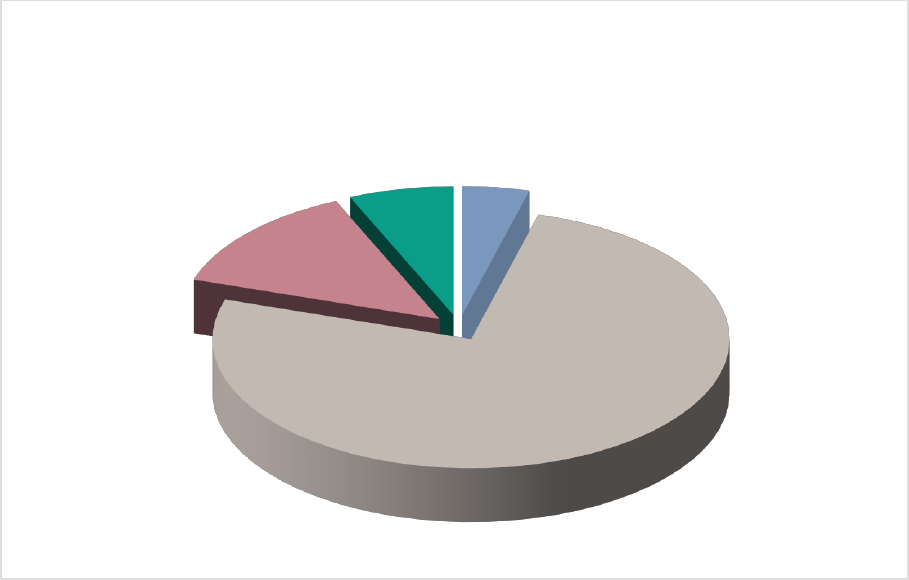

Their market share dropped to 8% and remains marginal compared with .COM domains (47%,

up by 3 pp) and ccTLDs (36%, down by 1 pp). The Other Legacy segment stood at 9% (-1 pp).

Overall, if we exclude two TLDs still experiencing a sharp decline (.CN and .TW), the general

trend was relatively positive for ccTLDs, despite a gradual return to pre-health crisis

momentum. Create operations in 2021 exceeded 2020 levels but remained below 2019 levels.

The .COM domain reaped greater benefits from the situation in 2021 than in 2020, but its net

balance fell 40% in the second half of the year compared to the first half. It is thus on a trend

similar to that of ccTLDs, perhaps strengthened by the price increase on 1 September 2021.

Other Legacy TLDs continued on a downward trend (-0.7%) but seem to be stabilising, with

relatively contrasting situations. .BIZ (+3%) and .ORG (+2%) experienced slight growth while

.INFO (-8%) while .MOBI (-15%) declined.

The regional dynamics of ccTLDs continue to be clearly defined. Latin America and the

Caribbean recorded the highest growth rate (+18%) and thus continued to “catch up” to

Africa (+15%). North America posted 6% growth and Europe 3%. Lastly, Asia-Pacific,

7

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

constrained by the .CN and .TW domains, lost stocks of 14%. In two years (2020 - 2021), Asia-

Pacific has lost 8 points of market share in the ccTLD segment in favour of Europe (+4.5%),

Latin America and the Caribbean (+2.5), North America (+0.5) and Africa (+0.5).

ccTLDs continue to thrive best in Europe: out of 31 ccTLDs with over a million names, 18 are in

Europe, 7 in Asia-Pacific, 3 in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2 in North America, and 1 in

Africa.

Among the nTLD segments, Generic nTLDs fell 12% in stock and 8% in create operations (end

of the .ICU purge and other “Penny nTLDs) and Community TLDs 21% (-24% create operations).

Geographic TLDs were up 12% in stock and 41% in create operations, .BRANDs 7% (-23% create

operations) and “open” .BRANDs 5% (+67% create operations). The regular deletion process of

.BRAND TLDs and/or their conversion to generic domains has continued: 4 in 2019, 6 in 2020, 2

in 2021.

Retention rates are particularly high among .BRANDs (91%), relatively good for Geographic

TLDs (75%) and Community TLDs (74%), moderate for open .BRANDs (50%) and relatively low

for Generic TLDs (38%).

62% of new TLDs other than .BRAND had fewer than 10,000 names in portfolio, while 2% had

more than 500,000. For many of them (other than the .BRAND domains), these low volumes

constitute a serious impediment to breaking even and financing their development.

“Penny nTLDs” represent 25 TLDs and 16 million domain names (compared with 21 TLDs and

15 million names in 2020), i.e. 2% of nTLDs and 55% of the overall nTLD stock. However, the

composition of this very specific category is far from constant, with only 3 domains

considered “Penny TLDs” since 2019 (.ONLINE, .PRESS and .STORE).

The market of back-end registry operators acting on their own account or on behalf of third

parties is dominated by a few players, the three biggest of which are Ethos Capital

(Afilias+Donuts), CentralNic and GoDaddy with 35%, 17% and 8% of nTLDs managed

respectively for name volumes representing 19%, 44% and 9% of all the names registered as

nTLDs.

The study of the distribution of domain names in the various ICANN regions (by holders’

countries) shows that ccTLDs are still leaders in every region except North America, which is

dominated by the .COM domain. .COM gained ground overall in 2021 but with varied success

8

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

depending on the region. North America remains its focus region and the region in which it

is the undisputed leader.

Other Legacy TLDs and nTLDs are still very much in the minority, even in North America where

their market shares are most significant.

These data underline how difficult it is for new entrants to make their mark in the face of

cultural prisms that in one case prize notions of territory and proximity, and in the other case

(North America) favour a global approach and are wary of any reductive specific feature

induced by the TLD chosen.

The other major determinant of the market is location, the most powerful registrars being

located in North America (50% of registrars managing more than 1 million domain names,

but above all the world leader GoDaddy which manages 71 million alone). Their counterparts

in other regions are smaller, and sell ccTLDs just as well as, if not better than, gTLDs and nTLDs

in order to respond to local demand and to the competition to which it leads. The distribution

of Legacy TLDs and nTLDs by countries of groups of registrars shows North America leading

by a long way, with Europe lagging badly in terms of distribution by holders’ countries.

An analysis of the strategies of ICANN registrars demonstrates that most are positioned on

Legacy TLDs and nTLDs (64%), that 30% only sell Legacy TLDs and 6% only sell nTLDs.

The dynamics of ICANN registrars consolidated by region shows that North America and

Europe are more mature markets than Latin America and the Caribbean and Asia-Pacific,

which are more dynamic but also more volatile.

The concentration process continued in 2021 both horizontally and vertically. The major

players are also looking to position themselves on markets related to domain names, while

players that have developed outside of this market are successfully making their mark

(Google and Wix are among the top 10 global registrars, for example).

The still distant deadline for the 2nd ICANN round is causing uncertainty in the market and

adding impetus to the process of concentration insofar as players can solely envisage

buyouts of existing TLD to grow quickly instead of investing in the creation of new markets.

The development of commercial nTLDs continues to be a source of concern, as most have

not reached a size that allows them to exceed their break-even point. Their financial

9

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

situation and the difficulties in accessing the market caused by registrars unwilling to take

risks for new entrants also contribute to this concentration. This leads to sales of nTLDs to big

players able to obtain economies of scale and have their own registrars to reach target

audiences. Nevertheless, these players’ registrar networks seem to work in the same way as

those of their competitors, that is to say as “wholesalers” without targeting specific user

groups that could be directly interested in the TLDs held in the portfolio.

For these reasons combined, and as already commented in previous years, the registry-

registrar system will no doubt have to change in the future, by increasingly favouring the

emergence of specialised or proximity resellers who will market nTLDs to the relevant niche.

As regards the registries, services linked to data (including monitoring and security), the

improvement of DNS infrastructures and cybersecurity have remained the main avenues of

development and diversification alongside new services aimed at boosting sales

(suggesting attractive names, etc.). We are not, however, seeing fundamentally innovative

offerings emerge resulting from R&D initiatives, except for systems to detect potential abuse

of domain names and processes to identify holders using digital identity certificates which

are already used by some European ccTLDs. Yet despite the interest of this progress when it

comes to increasing the reliability of WHOIS bases, they are not strictly speaking commercial

offers.

The IoT (Internet of Things), on the subject of which an Afnic engineer recently published an

article

1

, could prove to be an important growth driver for registries in the medium term.

1

BALAKRICHENAN Sandoche. Evolving From an Internet Registry to IoT Registry, CircleID, 13/04/2022.

https://circleid.com/posts/20220413-evolving-from-an-internet-registry-to-iot-registry

10

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

3. Global trends

The domain name market (excluding Penny TLDs) represented approximately 352 million

names worldwide at end 2021, up by 0.9% from 2020 (349 million). Although the growth trend

shows a constant slowdown (+4.7M in 2019, +1.3% in 2020, +0.9% in 2021), an analysis of monthly

variations reveals that in reality, 2021 was the “trough” year and that the market was once

again on an upward trend at the end of year.

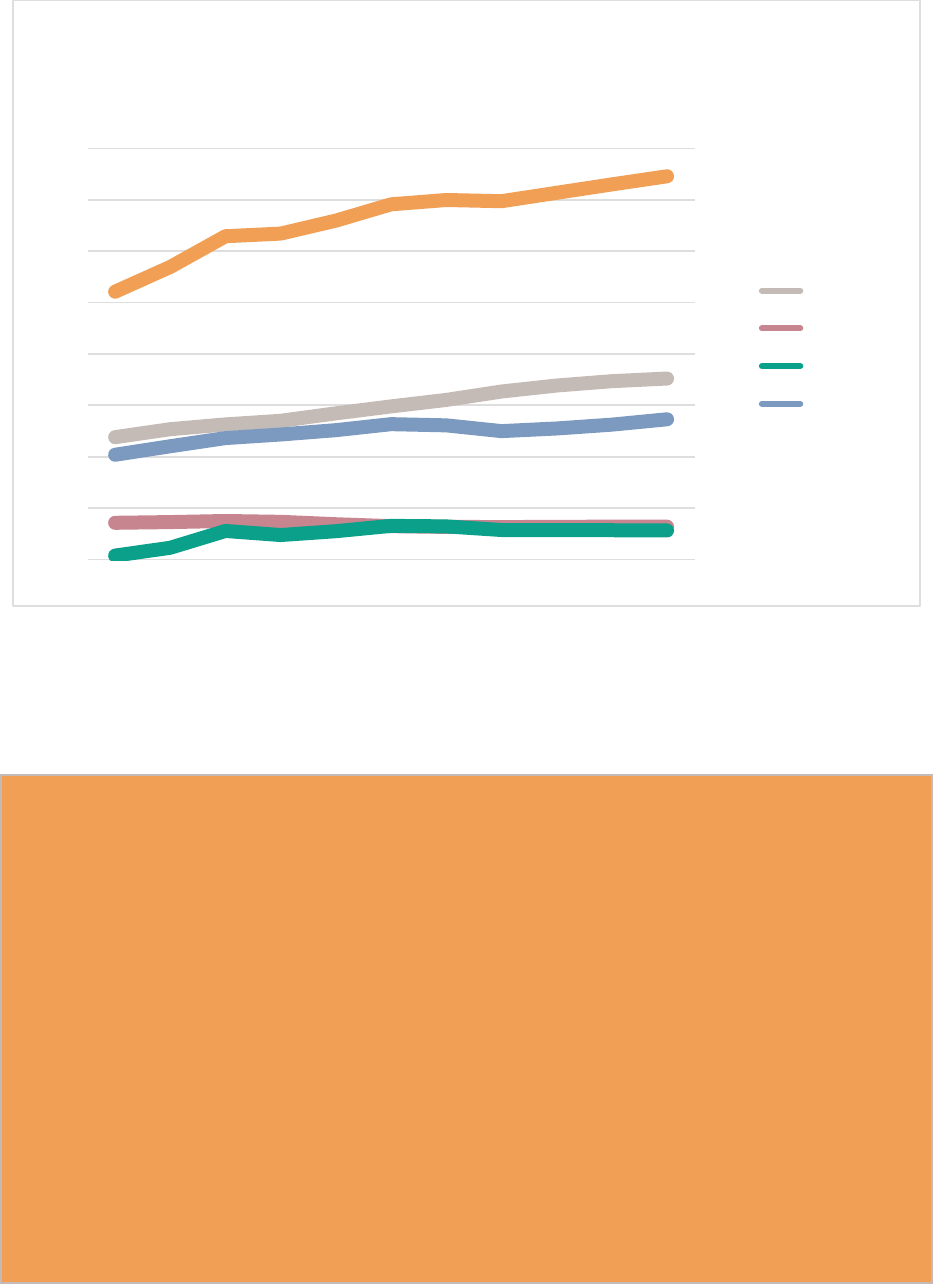

3.1. A return to normality?

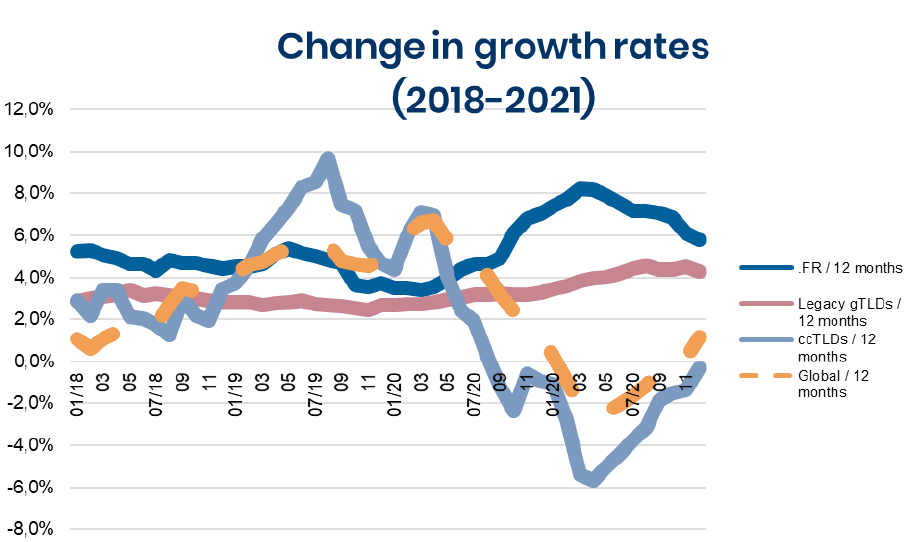

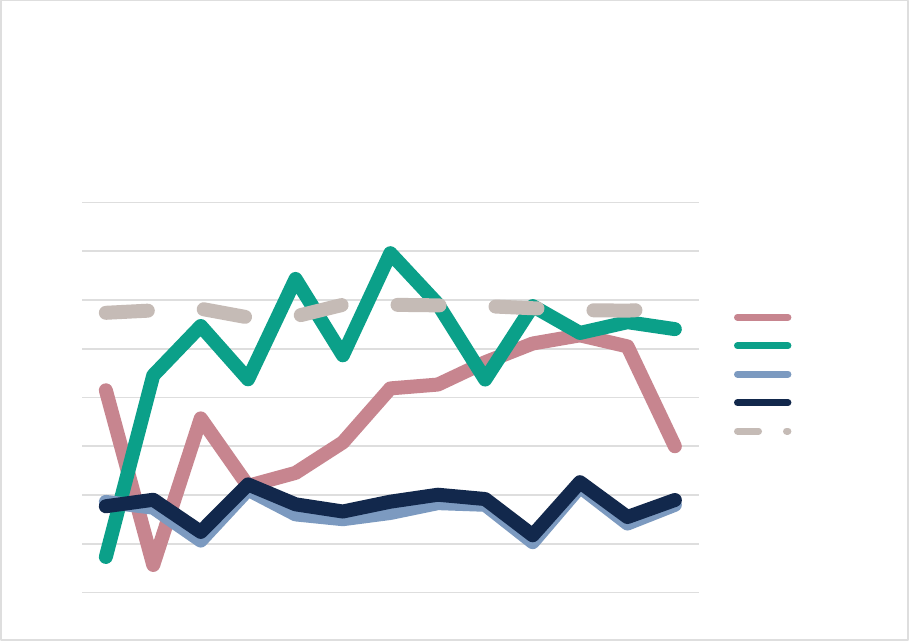

The following figure shows that despite strong contrasts in their developments in 2020 and

2021, the different segments were all headed towards a return to their pre-COVID growth

rates at the end of 2021.

Conditioned by that of .COM, the growth of Legacy TLDs continued to increase up until

Q3 2021 but seemed to slow down in Q4.

ccTLDs, meanwhile, lost stock between February and September 2021, but initiated a

spectacular recovery in Q4 which boosted the overall market performance.

.FR has followed an almost inverse trend (which reflects that of CENTR ccTLDS as a whole)

with steady growth up until Q1 2021 followed by a deceleration over the rest of the year.

11

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

In this report, we will explain the causes of these developments which may sometimes be

misleading, covering numerous distinct phenomena.

The new TLDs are not included in this figure because their large variations would overwrite

the other curves. These represented +15% in 2018 and +20% in 2019 but -1% in 2020 and -9% in

2021. These negative performances can be largely attributed to the after-effects of the

“purge” of the .ICU domain begun in 2021; they do not reflect the real dynamics of this market

segment.

3.2. Persistently contrasting performances

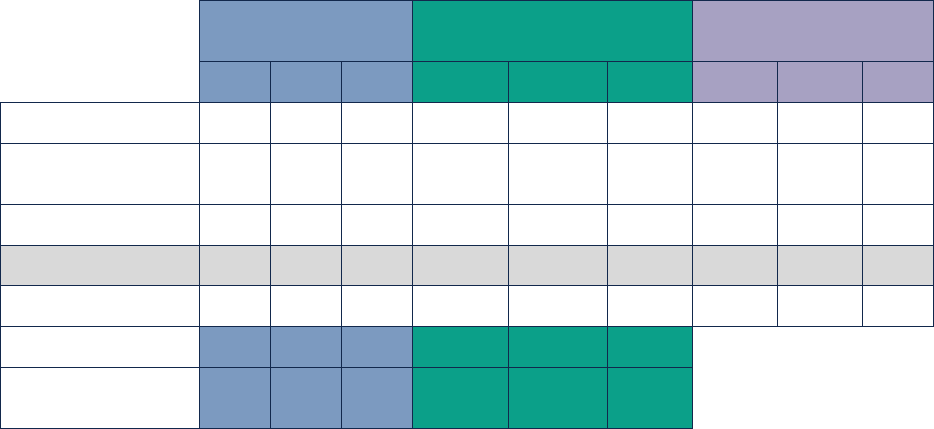

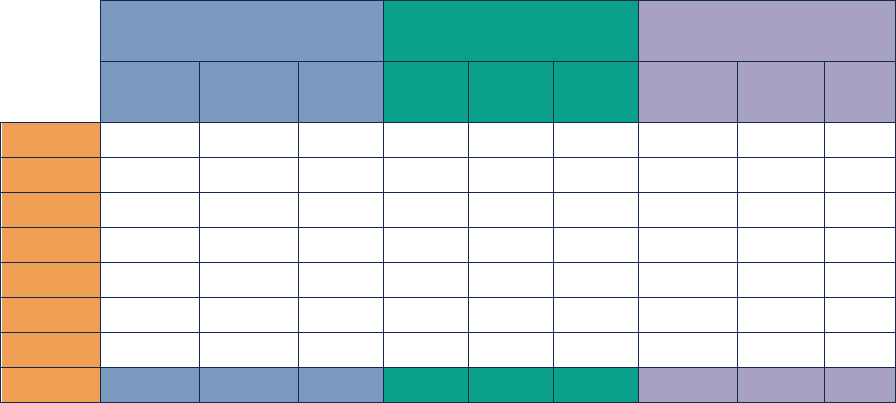

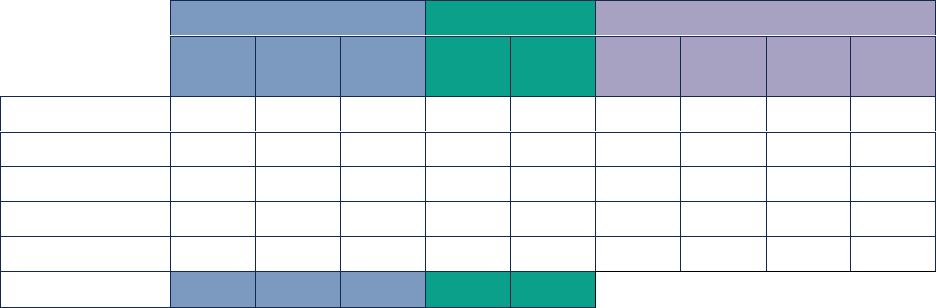

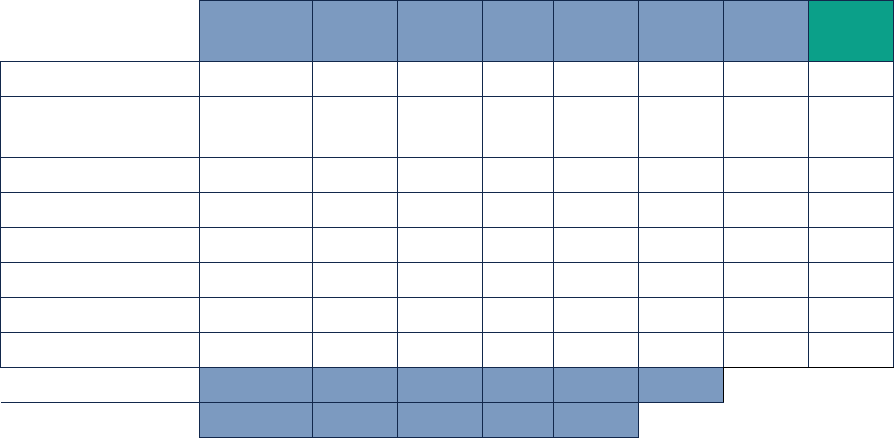

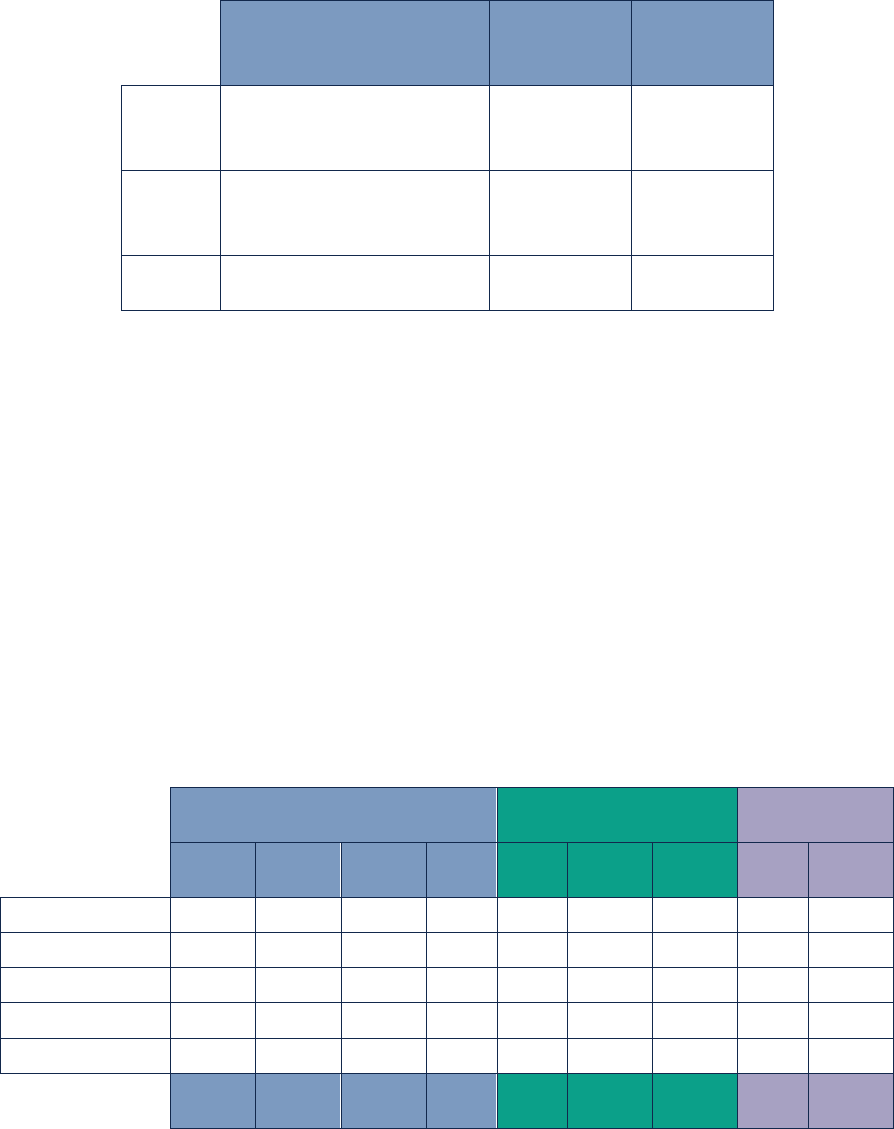

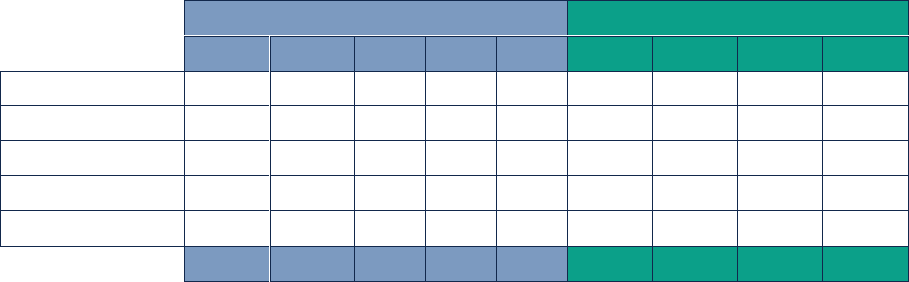

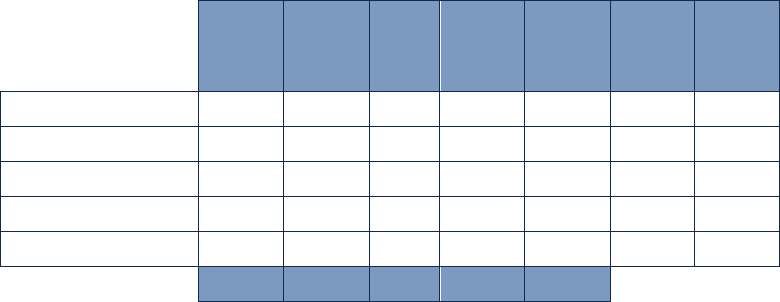

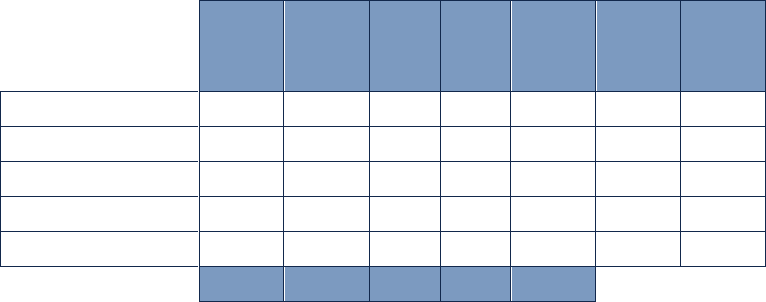

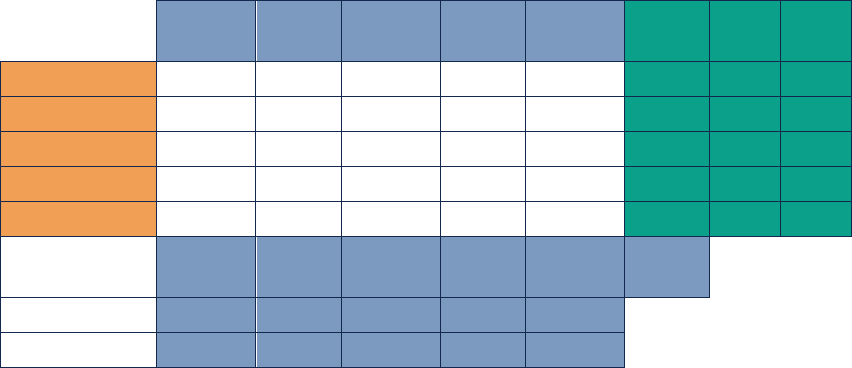

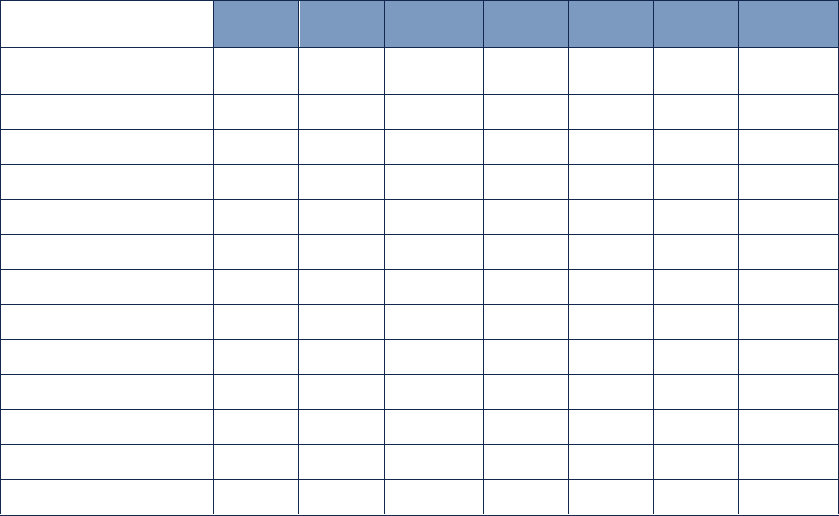

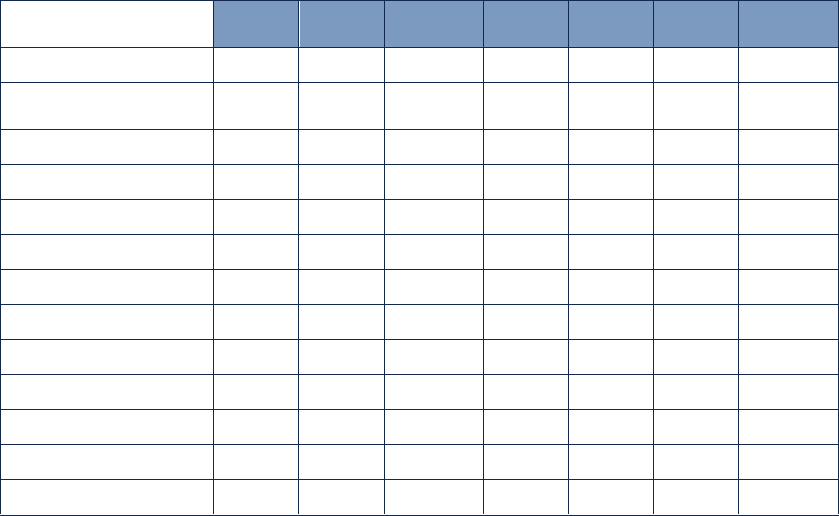

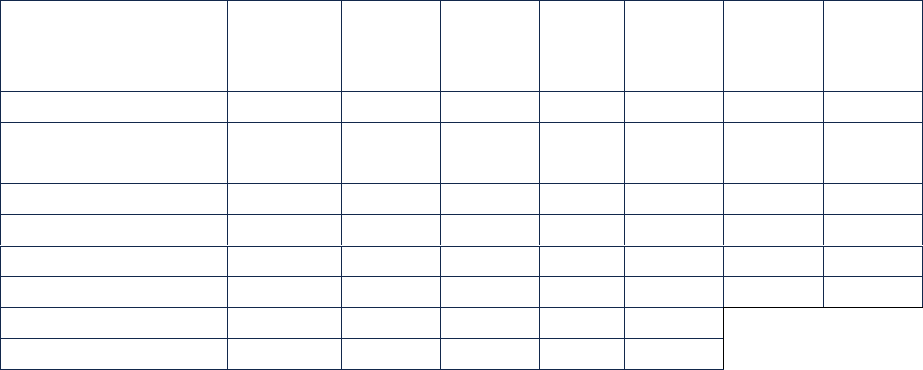

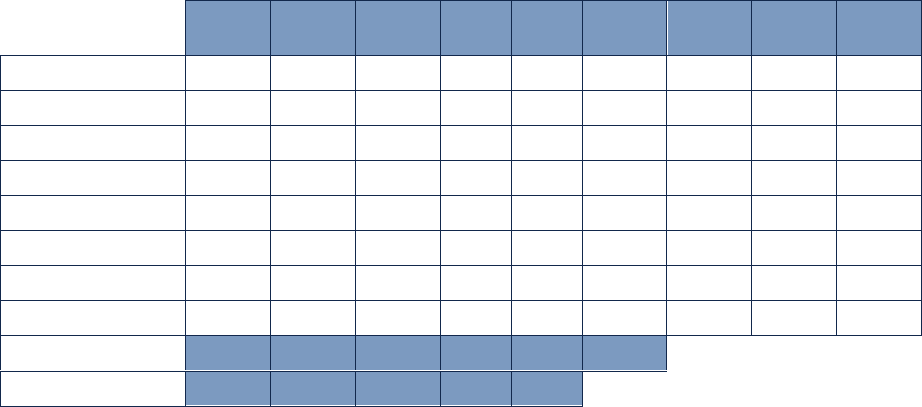

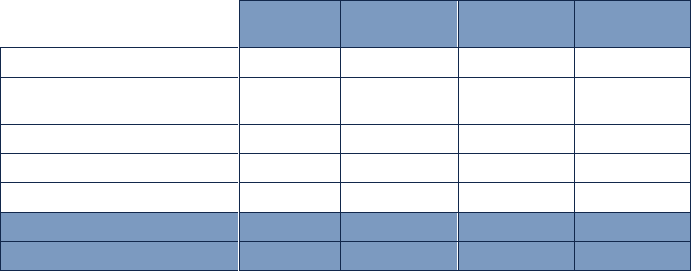

The table below shows the main indicators for each market segment between 2019 and 2021.

Stock

(m DNs)

Variations (%)

Market share (%)

2019

2020

2021

2019

2020

2021

2019

2020

2021

.COM

149

155

164

4.8%

4.4%

5.8%

43%

44%

47%

Other Legacy

TLDs *

32

32

32

-6.0%

-1.8%

-0.7%

10%

10%

9%

nTLDs

33

32

29

19.2%

-1.0%

-9.4%

9%

9%

8%

Total gTLDs **

214

219

227

4.9%

2.6%

3.7%

62%

63%

64%

ccTLDs ***

132

130

125

4.7%

-0.9%

-3.8%

38%

37%

36%

TOTAL

346

349

352

4.7%

1.3%

0.9%

Penny ccTLDs

****

49

41

27

54.9%

-15%

-34.1%

Performance indicators for the major segments (2019 – 2021)

m DNs: Year-end data expressed in millions of domain names.

* Other Legacy TLDs: generic TLDs created before 2012, such as .AERO, .ASIA, .BIZ, .NET, .ORG, .INFO, .MOBI, etc.

** Total gTLDs: measures all the domain names managed under a contract with ICANN. This includes the new TLDs,

some of which are not, strictly speaking, “generic”.

*** ccTLDs or "country code Top-Level Domains", i.e. domains corresponding to territories, such as .FR for France. The

data presented do not include “Penny TLDs” i.e. ccTLDs retailed at very low prices, if not free of charge. These ccTLDs

are subject to very large upward and downward movements that do not reflect actual market developments and

distort aggregate data.

**** Penny ccTLDs: estimated volume of names filed in these “low-cost” or free domains.

With 164 million names (+8 million in 2021 compared to 6 million in 2020), the .COM domain

remains the leader and continues to increase its market share (+3 pp).

12

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

The “Other Legacy” TLDs continued to lose stock in 2021, but less markedly than since 2018.

The trend towards stabilisation is continuing.

New TLDs posted a stock decline (-9%) despite being in a “recovery” phase since summer

2021.

Country TLDs (ccTLDs) ended the year in the red overall (-4%) although they experienced

regrowth since Q2 2021. This below-average performance is in reality determined by a small

number of ccTLDs.

This contrasting behaviour has impacted market share with the rise of .COM (+3 pp) to the

detriment of Other Legacy TLDs (-1 point), nTLDs (-1 pp) and ccTLDs (-1 pp).

We will be looking in more detail at how each segment experienced 2021, which marked the

transition towards a “post-COVID” world where the achievements of the acceleration of the

digital transition still made themselves felt.

3.3. nTLDs: surface tumult and baseline

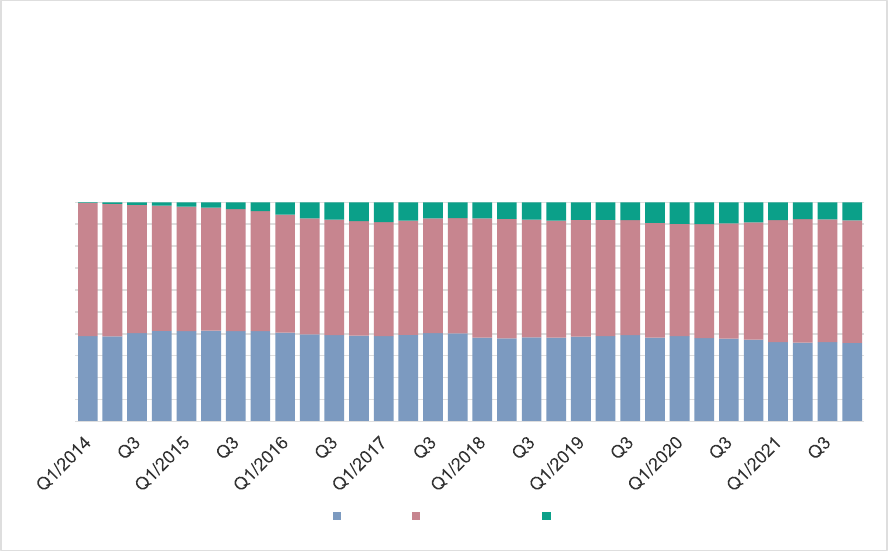

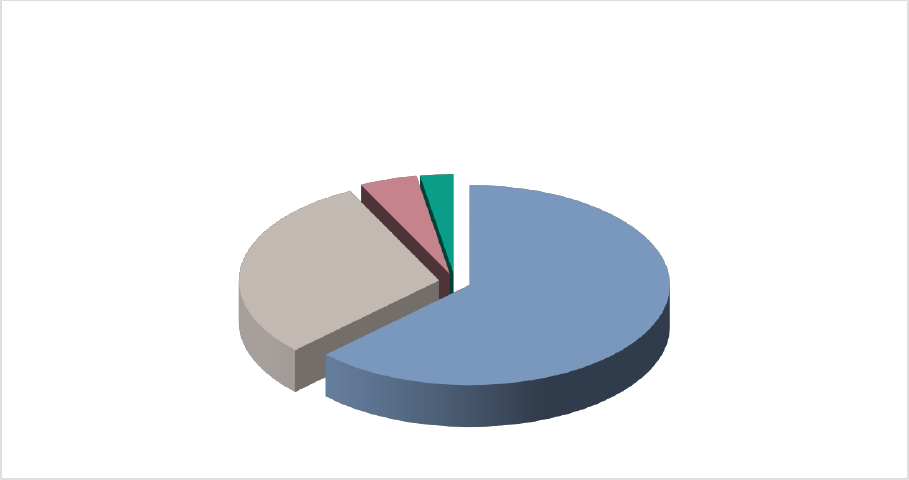

development

The chart below shows a quarterly view of the change in market share of the various

segments since the introduction of the first nTLDs in January 2014.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Change in market share

per type of TLD

(2014-2021)

ccTLDs Legacy gTLDs nTLDs

13

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

Note the sustained growth of nTLDs up to Q1 2017, followed by a period of decline in Q2 and

Q3 2017 and stabilisation up to Q3 2019. At the end of 2019 there was a new uptick due to the

.ICU domain, but not enough to pass the 10% market share mark. A decline can be observed

in Q3 and Q4 2020. The situation subsequently remained stable overall in 2021.

Trends in nTLDs are often reflected in those in ccTLDs, with gTLDs remaining stable or

increasing their share only marginally. This finding confirmed in 2014 – 2020 was not

confirmed in 2021 with a fall in nTLDs and ccTLDs combined with the strong growth of .COM

which more than offset the decline in Other Legacy TLDs.

This pattern may be specific to 2021 but does not negate the observation made in previous

editions of the Observatory. The 20/80 rule (and even the 5/95 rule) still applies: a small

number of TLDs account for the bulk of the net balance (positive or negative), thus masking

the performances of the other TLDs.

3.4. Strengthening of .COM positions in 2021 as

in 2020

The same data expressed as net balances highlight the weight of the different segments in

the overall performance of the market in 2021.

As in 2020, we see that in a context in which the 3 other segments (Other Legacy TLDs, ccTLDs

and nTLDs) were losing stock, the .COM domain, which was growing, acted as a driver for the

market.

The data in absolute values allow us to establish orders of magnitude. Thus the net balance

of the .COM domain alone in 2021 (8 million names) represents twice that of the market as a

whole.

Net balances

(millions of DNs)

Weight in the total

2019

2020

2021

2019

2020

2021

.COM

6.8

6.5

8.2

43%

148%

202%

Other Legacy TLDs

-2.1

-0.6

-0.2

-13%

-14%

-5%

nTLDs

5.3

-0.3

-3.5

33%

-7%

-87%

Total gTLDs

10.0

5.6

4.4

63%

127%

110%

ccTLDs (excluding “Penny”)

5.9

-1.2

-0.4

37%

-27%

-10%

TOTAL

15.9

4.4

4.0

-

-

-

Net balances of the major segments (2019 – 2021)

14

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

These data give us some idea of the relative positions and dynamics of the major market

segments - Legacy TLDs, ccTLDs and nTLDs - but they do not explain them. Now let us take a

closer look at each of these three segments to try to better understand the phenomena at

work in 2021.

15

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

4. Legacy TLDs in 2021

There are now 18 “Legacy TLDs”, or “traditional” domains created before 2012: AERO, ASIA, BIZ,

CAT, COM, COOP, INFO, JOBS, MOBI, MUSEUM, NAME, NET, ORG, POST, PRO, TEL, TRAVEL and XXX.

The stocks of these Legacy TLDs vary enormously, from the handful of names in the .POST

domain to the 164 million of the .COM domain.

In order to present relevant summary tables and indicators, we shall distinguish only the six

biggest in volume terms, aggregating the other 12 under “Others”.

In 2021, the global Legacy stock grew by 4.8% while create operations appreciated by 5.4%.

The retention rate improved slightly to 79% compared with 78% in 2020.

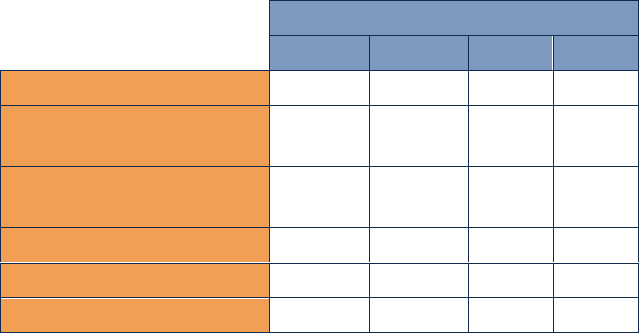

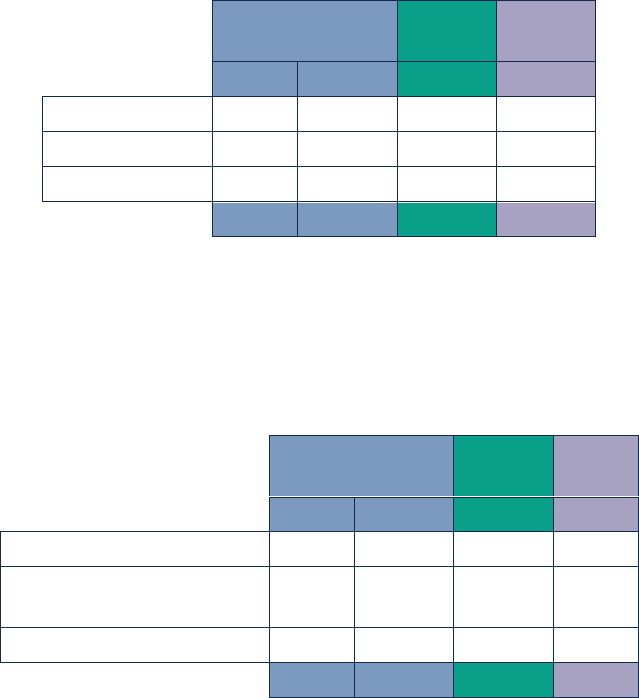

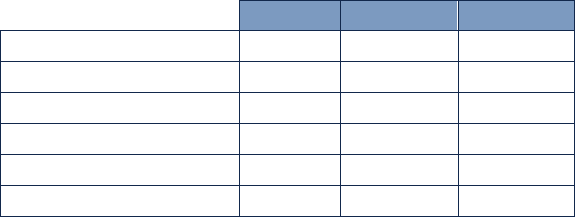

Nevertheless, the table shows the extent to which the situations vary.

Stocks (thousands)

Create operations

(thousands)

“R” (thousands) (*)

2020

2021

Var. %

2020

2021

Var. %

2021

%

2021

%

2020

.BIZ

1,441

1,487

3.2%

232

296

27.6%

1191

83%

74%

.COM

155,320

163,501

5.3%

39,421

41,880

6.2%

121,621

78%

78%

.INFO

4,455

4,094

-8.1%

1,036

802

-22.6%

3,292

74%

69%

.MOBI

380

324

-14.7%

41

30

-26.8%

294

77%

78%

.NET

13,704

13,702

0.0%

2,561

2,660

3.9%

11,042

81%

81%

.ORG

10,788

11,023

2.2%

2,013

1,867

-7.3%

9,156

85%

84%

Others

983

912

-7.2%

217

197

-9.2%

715

73%

68%

TOTAL

186,088

195,044

4.8%

45,305

47,732

5.4%

147,312

79%

78%

Performance of the major Legacies (2020 – 2021)

(*) “R” refers to the number of domain names retained in 2021. This figure is obtained by a fairly simple equation: R =

Stock at 31/12/2021 – Create operations 2021.

This is because the stock of a TLD at the end of 2021 is mathematically constituted by the names of the stock as at

31/12/2020 retained in the portfolio to which have been added the domain name creations of 2021. It is therefore

possible to deduce a “retention rate” based on these data from the various registries at ICANN [% R] for the names

that were in stock at the end of 2020.

R rate 2021 = R / Stock 2020

This retention rate should not be confused with the Renewal Rate, which only concerns the names that were up for

renewal during the year in question. Names filed for several years are “retained” but not “renewed”.

16

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

4.1. The .COM domain versus Other Legacy

TLDs: persistently contrasting situations

The data presented above show that the situations of the main Legacy TLDs differ

profoundly.

.COM dominates in terms of volume (it accounts for 84% of all Legacy TLDs) and growth,

which outstrips that of Other Legacy TLDs thanks to rising create operations with a stable

retention rate.

Of the Other Legacy TLDs, .BIZ (+3.2%) and .ORG (+2.2%) are expanding, .NET has reached a

balance, and the others are losing stock: -14.7% for .MOBI, -8.1% for .INFO and -7.2% overall for

the others.

.BIZ seems to be getting back on its feet after a purge with a retention rate of 83% following

a poor year in 2020. .ORG had a high rate slightly up which offset the fall in its create

operations (-7.3%).

Generally speaking, retention rates are rising, but the Legacy TLDs most penalised in terms

of stocks are those that have seen their create operations plummet: -26.8% for .MOBI, -22.6%

for .INFO and -9.2% for the others.

It is as if users were less and less interested in these domains which were presented, at the

time of their creation in 2001, as alternatives to the near “saturation” of the .COM domain.

4.2. Legacy TLD creations during the post-

COVID phase

As already mentioned above, .COM saw its create operations increase by 6% in 2021 following

a 4% increase in 2020. The acceleration of the digital transformation was felt more acutely

for this TLD with a 6-month lag compared to ccTLDs.

In the 2020 Observatory, we attributed this phenomenon to the decline in create operations

carried out in 2020 by the major domainers which offset the create operations that resulted

from the lockdowns.

In 2021, the same causes worked in reverse at an interval generating a boom in the domain:

return of domaining and slowdown in post-COVID creations in a context of a 7% price rise as

of 1 September 2021.

This formative data could result in a serious drop in growth of the .COM TLD in 2022, forcing

domainers to rid their portfolios of “loss-making” names under the new price conditions.

17

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

The “new circumstances” can be seen in the last quarter of 2021 with an equivalent net

balance at just 60% of what it was in Q1 and Q2 (Q3 being impacted by the summer months),

but in line with the performance of the second half of 2020.

.COM

2021

In millions

Q1

Q2

Q3

Q4

Stock end of period

157.8

160.4

162.0

163.5

Quarterly create

operations

10.7

11.0

10.1

10.0

Quarterly delete

operations

-8.2

-8.5

-8.6

-8.5

Quarterly net balance

2.5

2.6

1.5

1.5

Q4 Retention Rate

77.8%

77.8%

78.2%

78.3%

Q4 Creation Rate

25.8%

26.2%

25.8%

25.6%

Quarterly indicators for .COM activity in 2021

The first half of 2021 saw a “fever pitch” in create operations that did not extend to the second

half of the year. The price effect, however, remains highly restrained: there has been no

collapse in create operations nor a flurry of delete operations. At most, growth has slowed

but not halted. The Creation Rate fell slightly but the Retention Rate increased. The state of

uncertainty remains. The first months of 2022 should give us a more accurate idea of the

impact of the price rise.

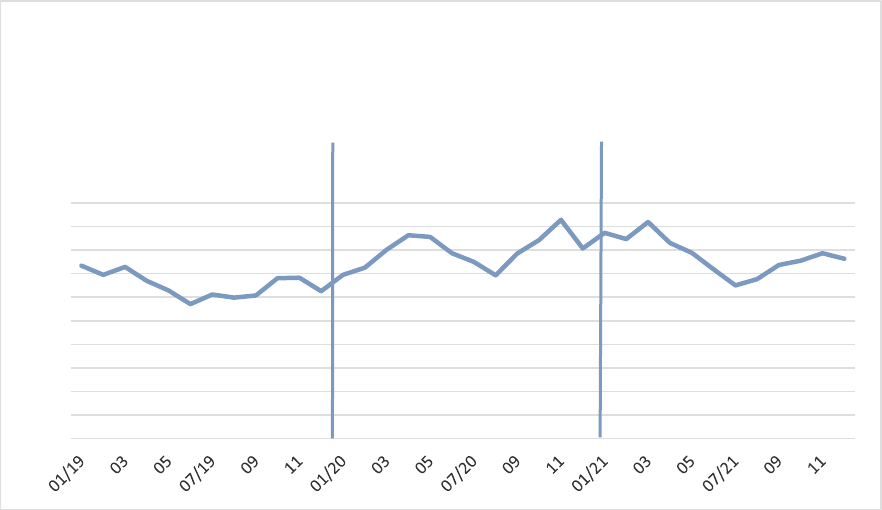

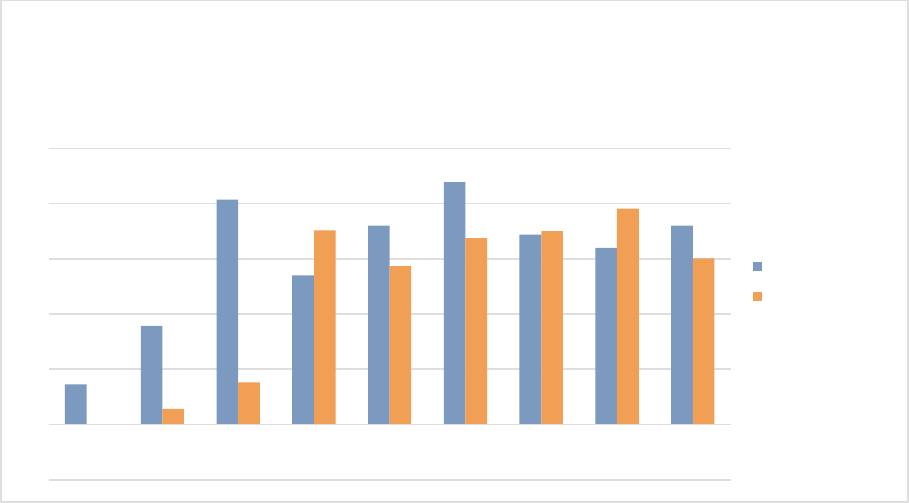

The graph below compares the create operations of the .COM domain with those of Other

Legacy TLDs and ccTLDs on a monthly basis.

18

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

The fever pitch was seen again in the first half of 2021, with the general downward trend over

the year despite the average level remaining above that of 2020. Creations returned to their

usual level in the second half of the year in the 3 – 3.5 million name range per month.

For Other Legacy TLDs, creations remained at the 500,000 per month level, dropping slightly

below as of Q2 2021.

nTLDs, however, saw their create operations surge sharply in the second half of 2021, even

exceeding the 1.5 million per month mark.

4.3. Retention rates up sometimes significantly

The retention rate is a key indicator for a TLD. On the one hand, it reflects the “loyalty” of the

domain name holders, providing clear information on the durability of the TLD. On the other

hand, the financial solidity of a registry depends essentially on the invoicing of renewal fees.

For a reasonably well-established registry, these annual fees generally account for more

than 75% of its total revenues. The growth dynamic comes from create operations, but the

basis of the registry activity is formed by renewals.

There are close links between the quality of create operations for a given year and the

retention rate for the following years. A “highly successful” free campaign can lead to mass

0

500

1 000

1 500

2 000

2 500

3 000

3 500

4 000

4 500

01/19

03

05

07/19

09

11

01/20

03

05

07/20

09

11

01/21

03

05

07/21

09

11

Monthly create in gTLDs (2019-2021)

COM

Legacy TLDs

other tant .COM

nTLDs

19

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

delete operations one year later. These rates must also be considered over time,

endeavouring to smooth out the variations linked to one-off events.

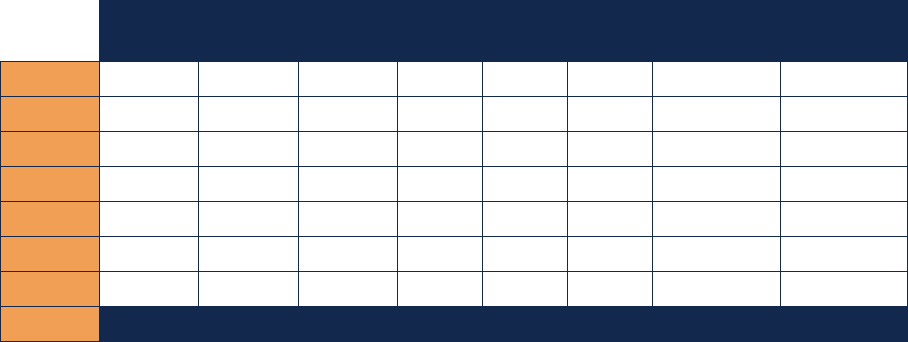

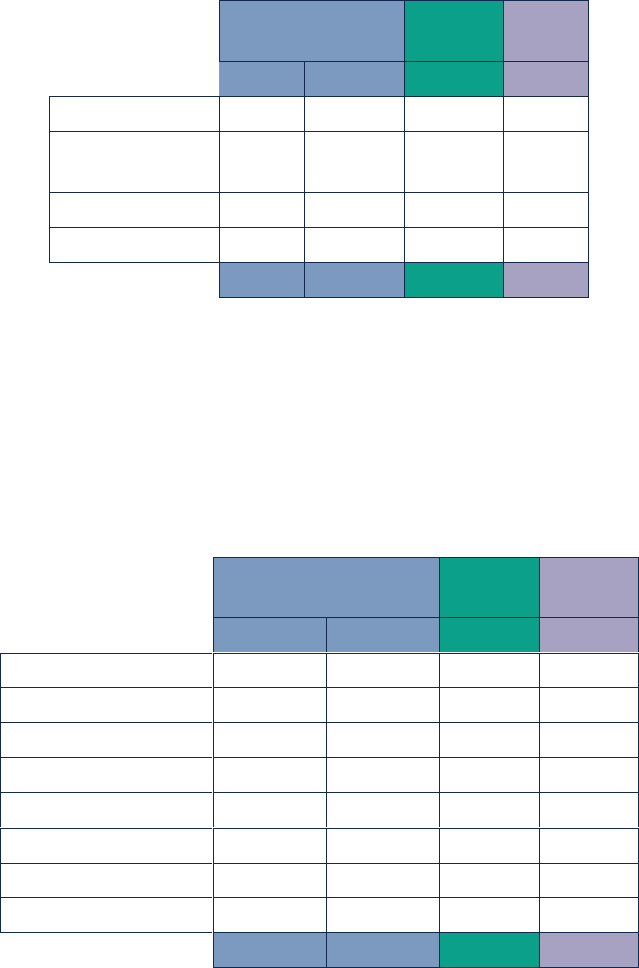

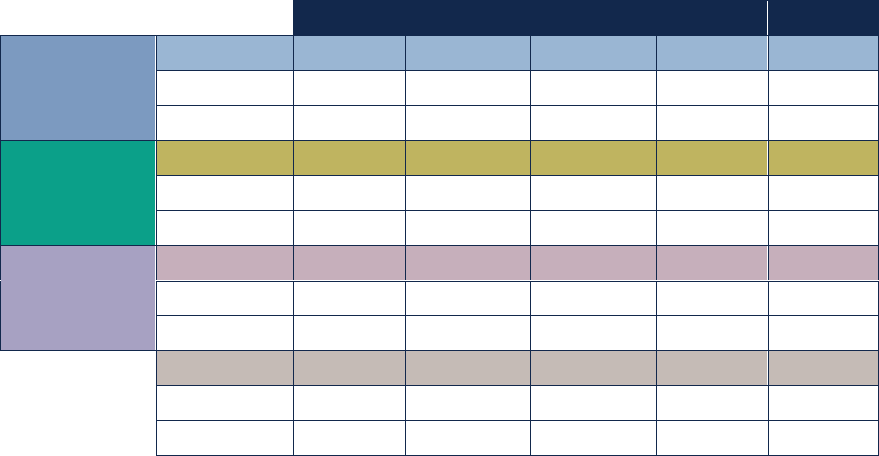

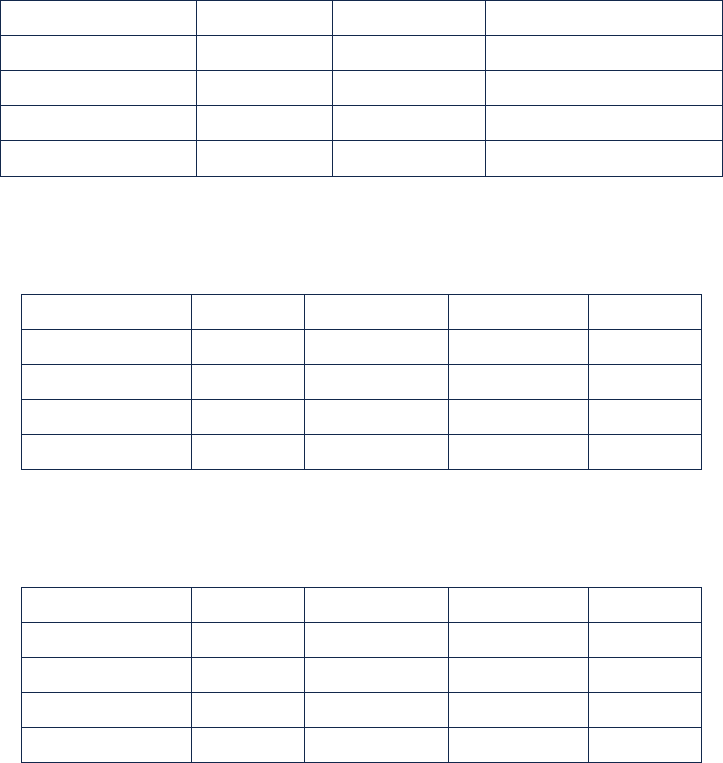

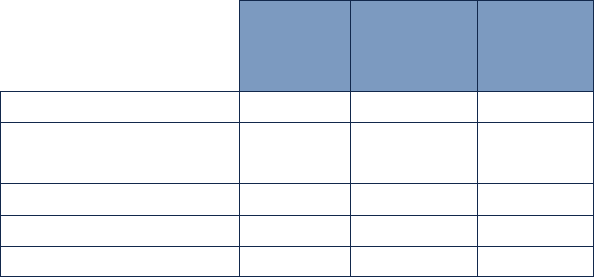

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Var. 20/21

(in pts)

Avg.

2016-2021

.BIZ

76.2%

66.4%

66.9%

58.4%

74.0%

82.7%

+8.7

70.8%

.COM

78.2%

77.4%

78.9%

78.1%

77.9%

78.3%

+0.4

78.1%

.INFO

76.6%

66.9%

57.8%

63.9%

69.2%

73.9%

+4.7

68.1%

.MOBI

76.6%

70.8%

78.2%

79.1%

77.8%

77.4%

-0.4

76.7%

.NET

79.6%

73.9%

77.1%

79.0%

81.1%

80.6%

-0.5

78.6%

.ORG

82.2%

79.6%

80.4%

81.9%

83.9%

84.9%

+1

82.2%

Others

82.5%

64.8%

73.6%

72.0%

68.4%

72.7%

+4.3

72.3%

TOTAL

78.5%

76.6%

77.8%

77.7%

78.2%

79.2%

+1

78.0%

Change in Retention Rates for Legacy gTLDs (2015 – 2021)

The above table shows the profiles of the strategies adopted by the registries.

If we concentrate on the 6 major Legacy TLDs between 2016 and 2021, we can see that .INFO

(68%) and .BIZ (71%) are the two domains with the lowest retention rates. These domains were

the subject of aggressive promotional campaigns that ended the following years with

equally massive deletions resulting in a discernible deterioration in the Retention Rate.

Inversely in 2020, such expansive promotional campaigns were not possible and 2021

Retention Rates improved appreciably.

.ORG is the most stable TLD over the period with an 82% Retention Rate and close to 85% in

2021.

These data are fundamental for the registries: a low retention rate creates the obligation to

offset deletions with creations so as not to lose stock. Overly aggressive low-cost strategies

lead to vicious cycles in which the registry finds itself forced to boost its creations to

maintain its stock, thus causing the quality of the stock to deteriorate even further by

encouraging speculative registrations that are not followed by lasting use. The sometimes

spectacular collapse in stocks that can be seen in some nTLDs corresponds to situations

where the registry has not been able to maintain the “kite flying” system it had tried to put in

place.

Conversely, a TLD with an exceptionally high retention rate but that does not encourage

creations becomes the archetypal cash cow, living on its stock as long as the names are not

abandoned by their owners. This situation, although a caricature, could await certain Legacy

TLDs in the future.

20

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

4.4. Implications in terms of naming strategies

We have already noted that the improvement in retention rates of certain TLDs could be

linked to the end of the “purges”, that is to say that the names remaining in the portfolio are

intended to be kept in increasing proportions.

There are four main reasons for keeping a domain name:

1. (a) because it is used and therefore important for its holder;

2. (b) because the holder wants to keep the name even if they are not using it at present

(ongoing project, conviction that the name will gain value, etc.);

3. (c) because it corresponds to a brand that the holder wants to protect (defensive

domain registration)

4. (d) because the holders are lacklustre in the management of their domain names

and renew the names without questioning the merits of the operation.

Of these reasons, (a) and (b) are the strongest as they are related to uses or to a perception

of value. (c) and (d) are the weakest and very sensitive to price changes and to the

appearance of new TLDs that may need to be registered. This leads to disposals in a context

where budgets are not infinitely expandable. The sums spent on defensive registrations in

Legacy TLDs are allocated to other defensive registrations in the nTLDs, and the holders who

have managed their portfolios in a poorly optimised manner are forced to adopt

optimisation strategies. It seems indeed necessary, to reduce costs, to limit creations in

relatively unattractive and/or low-risk domains since they are less and less well known to

users.

It is more than likely that the Legacy TLDs (except .COM) suffer from these disposal strategies

that dry up their create operations and force them either to practice aggressive

promotional campaigns to temporarily maintain their stocks, or to assume a certain decline

while looking for ways to retain their current holders.

The good health of the .COM domain in terms of create operations (+6% in 2018, +7% in 2019,

+4% in 2020, +6 in 2021) is likely due to a refocusing of users in 2020 and 2021 on the TLDs they

know best. New entrants forced to register names to develop their online presence are

effectively less mature than their predecessors and are even less knowledgeable of domain

names. They choose what they know, that is to say primarily their national ccTLDs (except

for Americans) and .COM.

These different phenomena (the refocusing of create operations, the disposals of retained

names, a relative loss of interest in defensive registrations and speculative operations)

largely explain the decline of the "Other Legacy TLDs", the difficulties of many nTLDs in finding

their market, and the relative good health of .COM and the main ccTLDs. The slowdown in

domaining and the acceleration of the digital transition, which have contrary effects on

creations, are two new factors that have been grafted on to the pre-2020 context.

21

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

The end of the “crisis” in 2021 led to a return to pre-COVID levels in the second half of the year,

without any gain in terms of the acceleration of the digital transition. We shall now examine

whether the same is true of ccTLDs.

22

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

5. ccTLDs (country-code Top-Level Domains)

Taken as a whole, ccTLDs lost 3.8% in stock in 2021 compared to -0.9% in 2020. But the overall

figure does not reflect the reality experienced by most ccTLD registries in 2021, which was

that of sustained activity although less intense than in 2020.

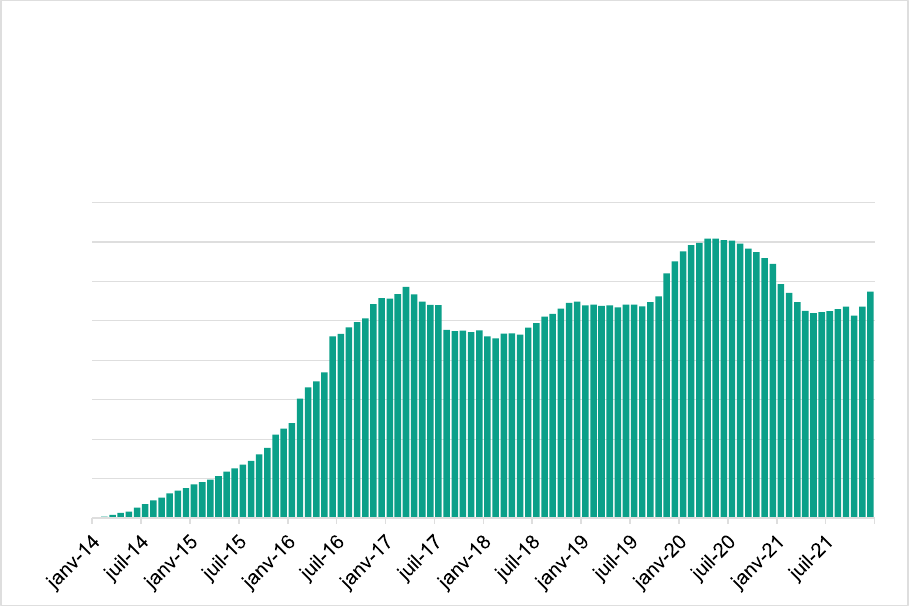

5.1. ccTLD creations during the post-COVID

phase

ccTLD creations generally slowed in 2021 compared to 2020 while remaining above 2019

levels. This no doubt reflects the impact of the acceleration of the digital transition brought

about by the lockdowns.

Uncertainty remains as to whether this trend will last: will create operations remain at this

level in 2022 or will they gradually return to 2019 levels?

A study conducted by CENTR of a sample of the biggest ccTLDs indeed shows that create

operations increased from a range of 80,000 to 1 million names a month to one of 600,000 to

800,000 names, as prior to COVID.

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1 000

Monthly create

Main CENTR ccTLDs incl. .FR excl. .UK

(2019-2021)

23

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

If we look more closely at the data, we can see that the “stall” began in Q2 2021 compared to

2020 performances. The situation stabilised and improved in the second half of the year, but

the state of uncertainty remains.

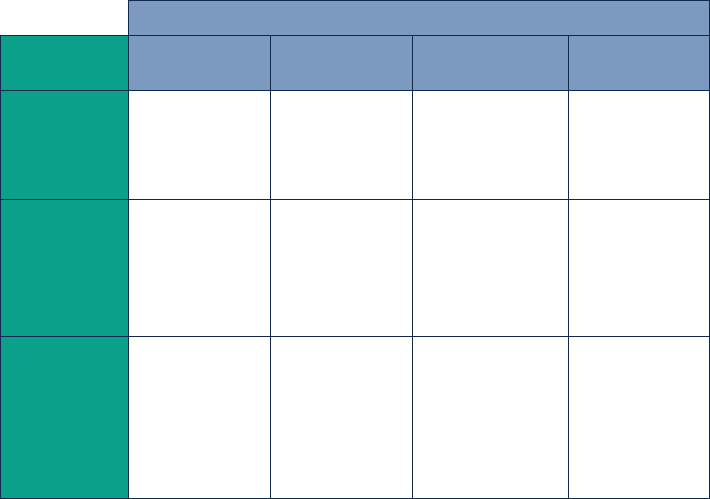

5.2. The regional dynamics of ccTLDs

The regional dynamics of ccTLDs were even more contrasted in 2021 than in 2020, mirroring

the economic situations of the different world regions.

Asia-Pacific continued its downward spiral with an overall loss of 14% in stock, i.e. around

5 million domain names. At the other end of the spectrum, Latin America and the Caribbean

(+18%) and Africa (+15%) stepped up their growth, as did North America (+6%). Europe returned

to positive growth (after the purge of .UK in 2020) though this remains comparatively modest

(+3%).

These developments have impacts on market share: although previously representing one-

third of names registered in ccTLDs in 2019, Asia-Pacific now represents just one-quarter;

Europe accounts for close to 60%, while Latin America and the Caribbean represent 10%.

Data excl.

Stock (millions)

Variations (%)

Market share (%)

“Penny”

ccTLDs

2019

2020

2021

2020

2021

2019

2020

2021

21/20

North America

4.6

4.7

5.0

1.7%

6.3%

3.5%

3.8%

4.0%

0.2

Latin America

8.6

9.7

11.5

13.5%

18.3%

6.5%

7.7%

9.2%

1.5

Africa

2.2

2.4

2.8

11.3%

15.2%

1.7%

1.9%

2.2%

0.3

Asia-Pacific

43.7

35.7

30.9

-5.4%

-13.6%

33.1%

28.5%

24.7%

-3.8

Europe

73.0

72.7

74.7

-0.5%

2.8%

55.3%

58.1%

59.8%

1.7

TOTAL

131.6

125.2

124.8

-0.9%

-0.3%

ccTLD performances by ICANN region (2020 – 2021)

24

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

Detail by region

We will now highlight the most pertinent variations for each region (generally over 100,000

names) and explain the reasons for the variations noted above, while at the same time

showing the extent to which the market continues to depend on a small number of TLDs.

North

America

Stock (millions)

Var.

(%)

Var.

(M)

2020

2021

2021

2021

.CA

3.0

3.2

6.8%

+0.2

.US

1.7

1.8

5.6%

+0.1

Others

0

0

4.3%

-

TOTAL

4.7

5.0

6.3%

+0.3

The leading ccTLD in North America is the .CA domain (Canada) with 3.2 million names. This

TLD continued to benefit from the acceleration of the digital transition in Canada, while the

.US domain returned to growth. These two TLD are the region’s drivers.

Africa

Stock (millions)

Var.

(%)

Var.

(M)

2020

2021

2021

2021

.ZA (South Africa)

1.2

1.3

7.9%

0.1

.IO (British Indian Ocean

Terr.)

0.6

0.8

34.3%

0.2

Others

0.6

0.7

11.9%

0.1

TOTAL

2.4

2.8

15.2%

0.4

The uncontested leader in the African region is the .ZA (South Africa) domain, with strong

growth of 8%. It is followed by the .IO (British Indian Ocean Territory) which grew by 34% in 2021.

The .IO domain, however, forms part of the “quasi-ccTLDs”, in other words it is sold as a

generic TLD, the more so as there are no longer any inhabitants in the territory concerned.

All the other African ccTLDs have relatively low volumes but considerable growth (+12%).

25

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

Latin America

Stock (millions)

Var.

(%)

Var.

(M)

& Caribbean

2020

2021

2021

2021

.BR (Brazil)

3.8

4.8

26.1%

1.0

.CO

(Colombia)

2.9

3.2

11.2%

0.3

.MX (Mexico)

1.4

1.3

-5.0%

-0.1

Others

1.6

2.1

32.0%

0.5

TOTAL

9.7

11.5

18.3%

1.8

The three leading ccTLDs in the Latin America and Caribbean region are .BR (Brazil) (+26%),

.CO (Colombia) (+11%) and .MX (Mexico) (-5%). However, the .CO domain is also a “quasi-gTLD”

since it is sold as an alternative to the .COM domain (and so far has not obtained the success

hoped for compared with the 164 million .COM names). In 2021, it was Brazil that most

contributed to the region’s net positive variation.

Asia-Pacific

Stock (millions)

Var.

(%)

Var.

(M)

2020

2021

2021

2021

.CN (China)

19.0

13.8

-27.1%

-5.1

.AU (Australia)

3.2

3.4

5.0%

0.2

.IN (India)

2.4

2.6

10.0%

0.2

.JP (Japan)

1.6

1.7

3.9%

0.1

.IR (Iran)

1.4

1.5

8.2%

0.1

.KR (South Korea)

1.1

1.1

1.3%

0.0

.TW (Taiwan)

1.5

1.0

-30.4%

-0.5

Others

5.7

5.8

2.3%

0.1

TOTAL

35.7

30.9

-13.6%

-4.8

The biggest ccTLD in Asia-Pacific is the .CN domain (China), variations in which, positive or

negative depending on the year, turbocharge or drag on the performances of the region as

a whole. .CN lost 1.7 million names in 2020, but according to our estimates, this loss stands at

over 5 million in 2021 (-27%). This below-average performance overwrites the aggregate net

balance for the region which, without the .CN domain, would be slightly positive. The other

ccTLD to have seen stocks fall dramatically is the .TW domain (Taiwan) with -500,000 names

(-30%). The other major ccTLDs in the region are on an upward trend, with the .IN domain

(India) even posting +10%.

26

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

Europe

Stock (millions)

Var.

(%)

Var.

(M)

TLD > 2M DNs

2020

2021

2021

2021

.DE (Germany)

16.7

17.2

2.8%

0.5

.UK (United

Kingdom)

10.9

11.1

2.1%

0.2

.NL

(Netherlands)

6.1

6.2

2.0%

0.1

.RU (Russia)

5.0

5.0

1.1%

0.0

.FR (France)

3.7

3.9

5.8%

0.2

.EU (European

Union)

3.7

3.7

0.9%

0.0

.IT (Italy)

3.4

3.5

2.2%

0.1

.PL (Poland)

2.5

2.6

2.2%

0.1

.CH

(Switzerland)

2.4

2.5

4.1%

0.1

Others

18.5

19.2

3.7%

0.7

TOTAL

72.7

74.7

2.8%

2.0

Europe is the region with the biggest number of large-volume ccTLDs. Its two leaders are .DE

(Germany) and .UK (United Kingdom), both of which have over 10 million domain names. Of

the ccTLDs with over 2 million names, .FR posted the strongest growth in 2021 (+6%); none of

the ccTLDs concerned recorded a net balance loss in 2021. The highest losses were posted

by .Рф (Russian Federation) (-37,000 names), .SU (Soviet Union) (-40,000 names) and .SE

(Sweden) (-89,000 names).

With the exception of .FR and .CH which have broken away from the pack, .RU (+1.1%) and .EU

which is struggling at +0.9% (due to the Brexit effect), most of the ccTLDs in our table are

relatively close to the regional average.

Breakdown of ccTLDs by volume bracket

The following table shows the distribution by volume bracket of ccTLD domain names in the

various parts of the world. We have taken account of all ccTLDs except “pennies” (see

hereunder) and IDNs, breaking them down into the same brackets as the nTLDs (see this

section) in order to facilitate comparison.

ccTLDs in IDN (internationalised domain name) format, that is to say in non-ASCII characters,

generally have confidential or zero volumes, with the notable exception of the .РФ domain

(Russian Federation in Cyrillic script) which has more than 700,000. It is the only IDN ccTLD

that we have included in our table.

27

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

Volumes

AF

LAC

AP

EU

NA

Total

2021

%

2021

%

2020

1 million or more

1

3

7

18

2

31

13%

12%

500,001 to 1

million

1

2

3

6

-

12

5%

5%

100,001 to 500,000

2

2

12

12

-

28

11%

12%

50,001 to 100,000

2

1

6

4

-

13

5%

6%

25,001 to 50,000

3

4

7

4

-

18

7%

5%

10,001 to 25,000

9

7

7

5

-

28

11%

11%

5,001 to 10,000

10

8

6

2

2

28

11%

12%

5,000 or fewer

28

22

28

7

1

86

35%

36%

TOTAL

56

49

76

58

5

244

%

23%

20%

31%

24%

2%

Breakdown of ccTLDs by volume range (2021)

This table clearly shows the inequality among regions, with Europe accounting for 50% of

ccTLDs with more than a million names (18 out of 31) and only 8% of those with fewer than

5,000 names (7 out of 86).

Although the “millionaire” category gained 1 point in “weight”, the others remain relatively

stable. The median stands at around 10,000 names, with the two least favoured categories

(less than 10,000 names) weighing 46% in 2021 compared to 48% in 2020. The three most

favoured categories (more than 100,000 names) represented 29% of ccTLDs in 2021, as in

2020.

We will come back to the distribution of domain names in the world later in the study with

some explanatory elements.

5.3. Weight of quasi-TLDs and Penny ccTLDs

To avoid bias due to their high volatility, we have excluded from our global tracking the

penny ccTLDs made specific by the aggressive marketing strategies of their registries. But

this does not detract from the interest of following this sample over time in view of its rather

atypical profile. The Penny ccTLDs identified are .CC (Cocos Islands), .CF (Central African

Republic), .GA (Gabon), .GQ (Equatorial Guinea), .ML (Mali), .PW (Palau), and .TK (Tokelau). No

others emerged in 2021.

The quasi-gTLDs remain included in the global tracking since their business models are more

traditional and do not resort to low-cost strategies. Their originality consists in using country

28

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

codes for generic purposes. In this study we consider the following domains as quasi-gTLDs:

.TV (Tuvalu - “Television”), .ME (Montenegro - “Me / Myself”), .CO (Colombia– “Commercial”),

.NU (Niue Island– “New” in Swedish), .IO (British Indian Ocean Territory), and .LA (Laos - “Los

Angeles”). We have added .VC (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines - “Venture Capitalist”).

If we make a distinction between the three ccTLD segments based on the marketing

strategies of their registries, the “true ccTLDs”, the “quasi-gTLDs” and the “Penny ccTLDs”, we

obtain the data collected in the table below.

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

ccTLDs

Stock

117.3

121.7

127.5

124.9

124.9

Variation

3.5

4.4

5.8

-2.6

-

Var. (%)

3%

4%

5%

-2%

-

Quasi-gTLDs

Stock

4.6

4.5

4.6

5.4

6.1

Variation

0.1

-0.1

0.1

0.8

0.7

Var. (%)

1%

-1%

3%

17%

13%

Penny

ccTLDs

Stock

24.9

31.3

48.6

41.2

27.4

Variation

2.0

6.4

17.3

-7.4

-13.8

Var. (%)

9%

26%

55%

-15%

-33%

TOTAL

Stock

146.7

157.5

180.6

171.5

158.4

Variation

5.6

10.8

23.1

-9.2

-13.1

Var. (%)

4%

7%

15%

-5%

-8%

Performance of the different categories of ccTLDs (2017 – 2021)

While “classic” ccTLDs have remained globally stable in 2021 (with the individual variations

covered above), quasi-gTLDs grew by 13% and Penny ccTLDs fell by 33% (mainly due to the .TK

purge).

Penny ccTLDs are found only in Africa and Asia-Pacific, as shown in the table below. The

figures indicate that in 2021, unlike 2020, African Penny ccTLDs recorded a fine performance

(+37% overall) in stark contrast to that of Asia-Pacific (-74% overall). These developments

reverse the weights of the two regions in terms of Penny ccTLDs.

29

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

Data

Stock (millions)

Variations (%)

Proportions (%)

Penny ccTLDs

2019

2020

2021

2020

2021

2019

2020

2021

21/20

Africa

19.6

15.0

20.6

-23%

37%

40%

36%

75%

+49

Asia-Pacific

29.0

26.2

6.8

-10%

-74%

60%

64%

25%

-49

TOTAL

48.6

41.2

27.4

-15%

-33%

-

-

-

-

Performance of Penny ccTLDs (2020 – 2021)

According to some sources, some of these registries do not delete names even if they are

unused and not renewed, which distorts the figures and provides yet another reason to

separate them from the other ccTLDs. This phenomenon is found also with nTLDs, which

complicates any analysis made of ongoing trends. As such, the spectacular purge of the .TK

domain in all likelihood affected names that could have been deleted in previous years. This

is a far-reaching adjustment that does not reflect the reality of the current dynamic of the

TLD.

30

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

6. nTLDs

It should be recalled that in many cases the only thing new TLDs have in common is the fact

that they are “new”… post-2012. This is not enough to classify them, since this characteristic

is disappearing as time goes by (and will disappear definitively at the time of the next ICANN

round).

All too often, observers refer to the success or failure of new TLDs without taking time to group

them into segments that make sense and allow for a more nuanced approach, criteria for

assessing performances being quite different from one segment to another.

That is why, having presented the overall trends in nTLDs, we will study each of

these segments in detail in order to gain a better understanding of their dynamics.

6.1. Global change in the stock of “new TLDs”

The historic peak in nTLDs reached in March 2017 at around 30 million names, following a

period of uninterrupted growth since January 2014, was exceeded in November 2019.

This upward movement was interrupted in 2020 following a high of 35 million names in

April/May. The decline accelerated from October with the start of the purge of the .ICU

domain. At the end of 2020, the number of nTLDs was essentially unchanged from the

beginning of the year. It also corresponded to the long-term trend that started in 2014/2015

and was resumed in October 2019 after the dislocations that followed the waves of mass

filings in 2016 and early 2017.

2021 was marked by a continued decline in the first half of the year, with a stabilisation over

the summer and a rebound in growth as of the autumn.

31

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

It is important to consider the long-term trend for this segment rendered volatile by

periodical waves of create operations followed the next year by large-scale delete waves:

.XYZ in 2015/2016 and .ICU in 2019/2020.

The graph above shows that after the “launch” period (2014 – early 2017), the stock of nTLDs

stabilised on the whole in the 23 million – 30 million range. The crossing of the 30 million

threshold in 2022 is therefore a positive sign for the development of nTLDS, if it is not due to a

new one-off wave of create operations.

An analytical grid taking account of the models and specific features of the nTLDs is

therefore essential in order to understand what is going on.

6.2. Definition of “new TLD” “segments”

We have created different segments corresponding to the most frequent approaches in

specialist circles. Since these TLDs are still relatively young, the uses made of them may lead

to revisions of this segmentation, which is still very much geared to the nature of the TLDs

and their conditions of eligibility:

0

5 000

10 000

15 000

20 000

25 000

30 000

35 000

40 000

Change in the number of names in

nTLDs

(2014 - 2021)

32

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

Community: domain name filings reserved to members of a community, use being

community-centric.

Geographic: nTLDs of a geographical character designating a city or region.

Generic: nTLDs consisting of generic terms.

Brands: TLDs corresponding in general to flagship brands, registered by private entities

for internal use or extended to their customers and partners.

“Open” brands: TLDs corresponding to brands, registered by businesses owning these

brands and open to holders other than the business, its subsidiaries or partners. These

TLDs are few in number (two after revision of the list in 2021: .CPA and .OVH) but the

volumes registered make this a fully fledged segment, comparable with that of generic

TLDs.

Our nTLD segmentation attempts to reflect the purpose of TLDs rather than their ICANN

status, since these are difficult to classify and have sometimes been adopted for tactical

reasons (such as to obtain the privileges granted to Community nTLDs). There is currently no

“official” nTLD nomenclature, so our segmentation is subject to change based on information

made public by the registries or ICANN.

An additional complicating factor is the degree of restriction required by each registry.

Access to a .BRAND domain can be relatively “open” (if the only condition to be met is, for

example, being a client of the delegatee) while the registration of a Generic TLD may also be

subject to conditions. https://ntldstats.com, which proposes a nomenclature, relies on a

framework that ranges from “Unrestricted” through “Semi-restricted” and “Brand” to

“Restricted”. However, while this approach may explain the volumes (or their absence) by

reference to eligibility conditions, it tells us nothing about the purpose and the marketing

positioning of nTLDs.

The .Brands converted in 2019 – 2021.

Moreover, since 2019, some nTLDS that were originally .BRANDs were altered in nature to

become generic TLDs. Below is the list of those we have had to reclassify, subject to

modifications if new information comes to our attention:

33

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

nTLDs

Previous

segment

New

segment

2019

.BOND, .COMPARE,

.MONSTER, .SELECT

.BRAND

Generic

2020

.BEAUTY, .CYOU, .HAIR,

.MAKEUP, .QUEST, .SKIN

.BRAND

Generic

2021

.BOX, .SBS

.BRAND

Generic

nTLDs that changed nature (2019 – 2021)

Certain players have developed a speciality in buying .BRAND domains unused since

creation from major groups. The “lines” dividing the segments therefore continue to shift,

proving that this market is alive and well.

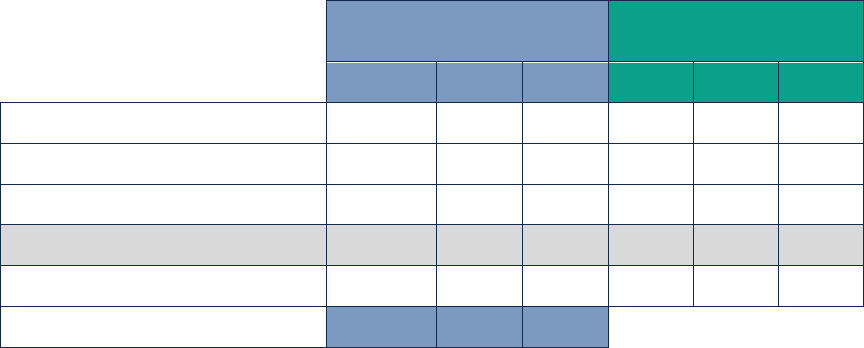

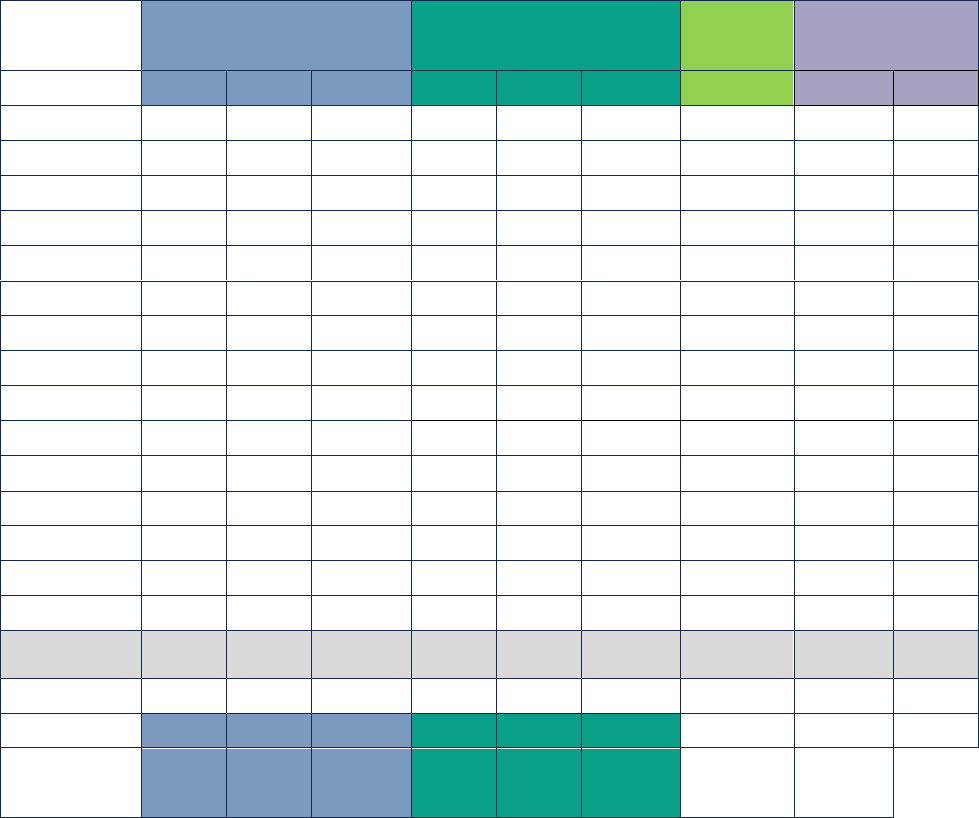

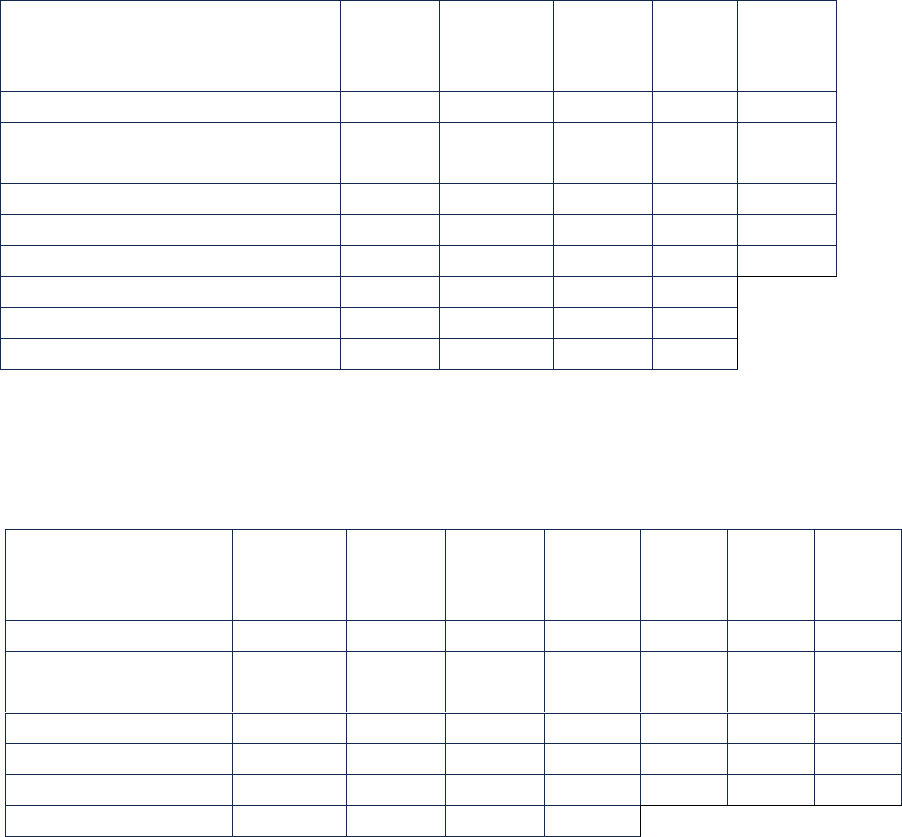

6.3. Performance of “new TLD” “segments”

The differences in dynamics observed for each of our segments show that the typology used

is relevant today. But this remains changeable. Undoubtedly nTLD families will continue to

refine in the future, requiring periodic revisions of the classification of these top-level

domains in order to keep as close as possible to market realities.

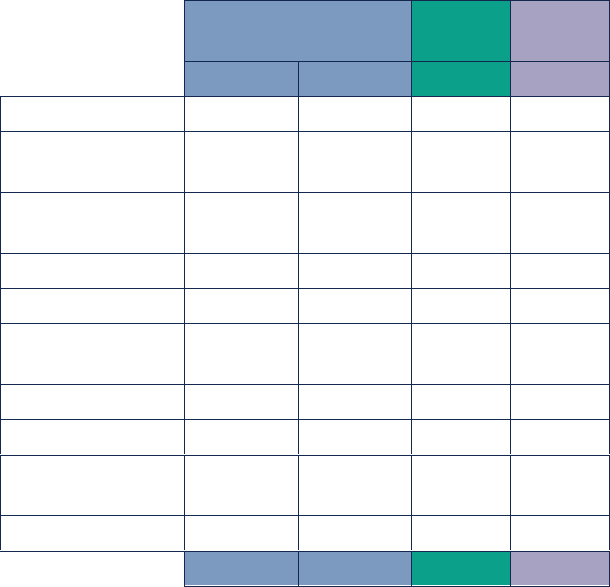

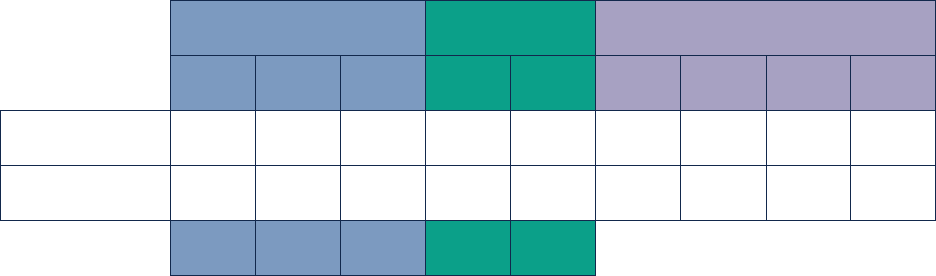

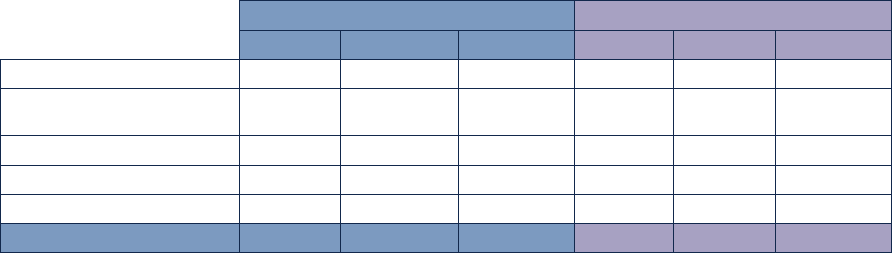

Stocks (thousands)

Create operations

(thousands)

Retention

2020

2021

Var.

abs

Var.

2020

2021

Var.

R.

2021

% R.

2021

Generic

31,197

27,568

-3,629

-12%

16,931

15,629

-8%

11,939

38%

Geographic

859

961

102

12%

233

329

41%

632

74%

Open brands

68

71

3

5%

23

38

67%

34

50%

Community

57

45

-12

-21%

3

2

-24%

42

75%

Brands

32

34

2

7%

7

5

-23%

29

91%

TOTAL

32,212

28,679

-3,533

-11%

17,196

16,004

-7%

12,67

5

39%

Performance of nTLD segments (2020 – 2021)

34

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

Generic TLDs lost 3,629,000 names in stock, which represents a 12% decline and explains the

negative variation of nTLDs since the three other segments are trending upwards. Generic

TLDs also experienced an 8% fall in create operations in 2021 (3.6 million names). Their

retention rate remained relatively low overall at 38%, but they are the most “dynamic” nTLDs

with a creation rate of 57% (15,629 / 27,568). Below we will examine the individual performance

of some of the generic TLD leaders.

Geographic TLDs gained 12% stock with a flurry of create operations (+41%) and a

“comfortable” retention rate of 74%. Their creation rate stood at 34% in 2021, which represents

a strong performance for this segment.

Open .BRANDs grew by 5% with a high number of creations (+67%, creation rate of 54%) and

an average retention rate (50%).

Community TLDs saw stocks fall 21% and creations 24%. Their 4% creation rate is a sign that

they are experiencing a serious problem with their sales dynamic that cannot be offset by a

75% retention rate.

Lastly, .BRANDs posted 7% stock growth and a 23% fall in creations. This phenomenon is

explained by a very high retention rate (91%) which offsets a relatively modest creation rate

(15%).

Change in the number of TLDs in each segment

The table below shows the change in the number of domains in each of the segments over

the last five years.

Number in

Variations (net balance)

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2018

2019

2020

2021

Community

12

12

12

12

12

-

-

-

-

Geographic

63

63

62

62

62

-

-1

-

-

Generic

506

511

517

524

526

+5

+6

+7

+2

Brands

633

622

594

573

555

-11

-28

-21

-18

Open brands

1

1

2

2

2

-

+1

-

-

TOTAL

1,215

1,209

1,187

1,173

1,157

-6

-22

-14

-16

Change in the number of nTLDs per segment (2017 – 2021)

After 2014-2016, which saw the creation and activation of most of the nTLDs (+465, +352 and

+313), 2017 and 2018 were marked by the first delete operations, which generally affected

.BRAND domains abandoned by their owners. This phenomenon continued in 2020, with the

loss of 21 .BRAND domains, 6 of which were converted to generic TLDs, and in 2021 with the

loss of 18 .BRAND domains, 2 of which were converted to generic TLDs.

35

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

The deletion of .BRAND domains follows a rationale specific to their registries reorientations

in the digital strategies of the groups concerned, changes of flagship brands making the

.BRAND domains concerned obsolete, or simply defensive create operations from the outset,

which their registries are unwilling to continue to pay for since they are at a loss as to what

use to make of them. The notion of “commercial failure” is not relevant to this “private”

segment.

The trend in conversions from .BRAND to generic TLDs is likely to continue, for two reasons:

on the one hand, the proportion of .BRAND names still not used is fairly large, which offers

prospects of acquisition/reconversion for a certain number, while others will be simply

abandoned;

and on the other hand, a significant percentage of generic TLDs have stocks of insufficient

volume to ensure the economic viability of their registries, which spurs the latter to

practice external growth strategies by buying the nTLDs available for sale.

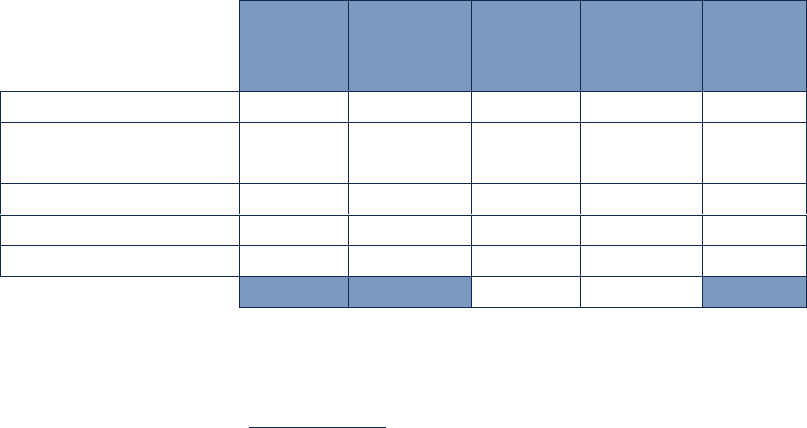

6.4. Distribution of new TLDs in volumes of

domain name registrations

The distribution in volume of domain name registrations does not reflect the number of TLDs

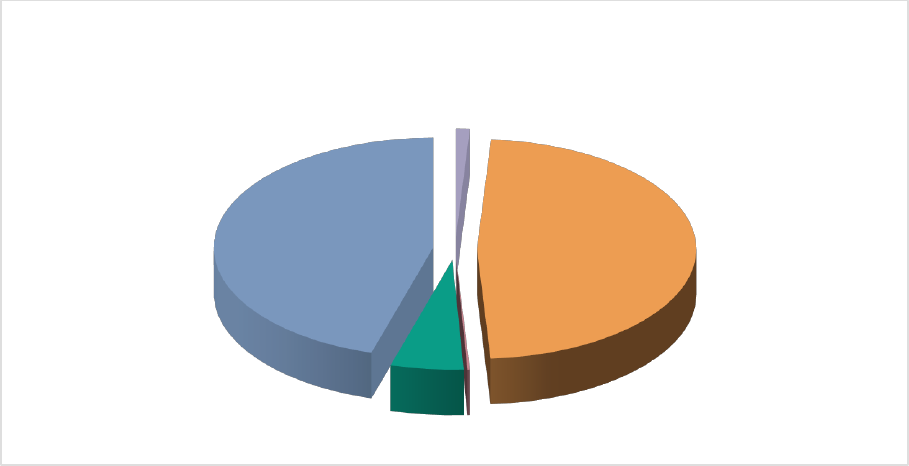

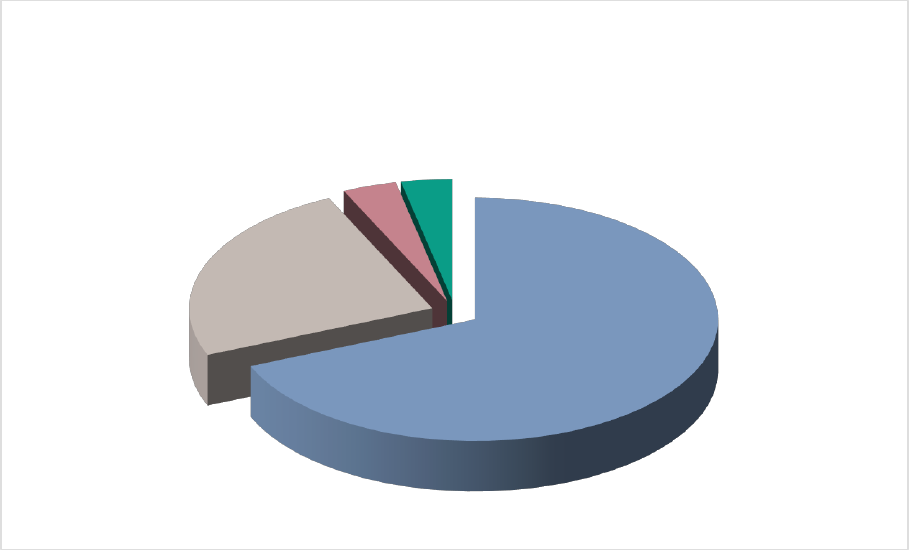

in each segment, as shown in the two figures below. With 526 TLDs (46% of the total) generic

TLDs represent 96% of domain name registrations; .BRAND domains meanwhile represent

only a marginal percentage of names registered with 555 TLDs (48% of the total).

Community TLDs

12

1%

.Brand

555

48%

.Brand open

2

0%

Geographic

62

5%

Generic

526

46%

Distribution of nTLDs by type (2021)

36

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

These two diagrams sufficiently illustrate the variety of business models and strategies of

each segment. .BRAND names generally respond to internal needs, while the Community

and Geographic nTLDs target customers meeting membership or location criteria. Finally,

generic TLDs can develop global ambitions as well as focusing on niche markets (or both at

once), depending on the potential represented by their terms. “Open” .BRAND names, for their

part, present characteristics in terms of volumes very similar to those of the generics, even

though they have eligibility conditions attached to them which sets them apart from generic

names.

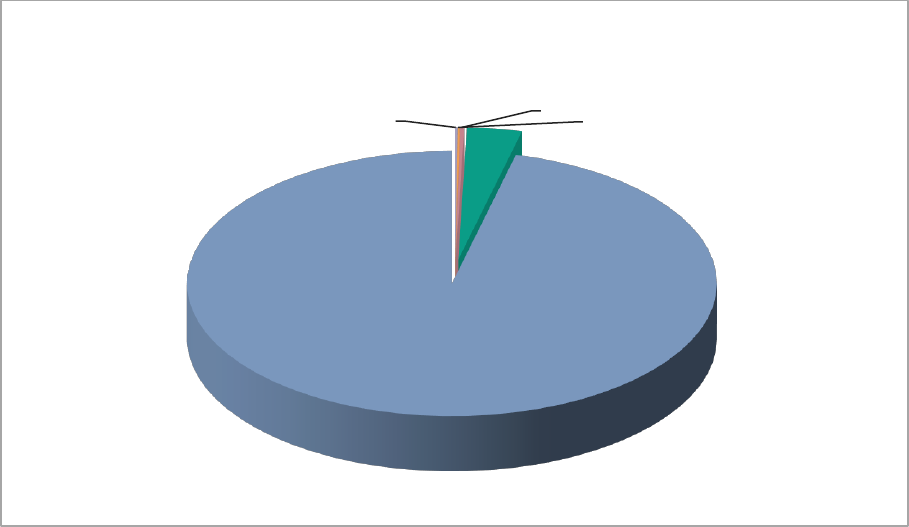

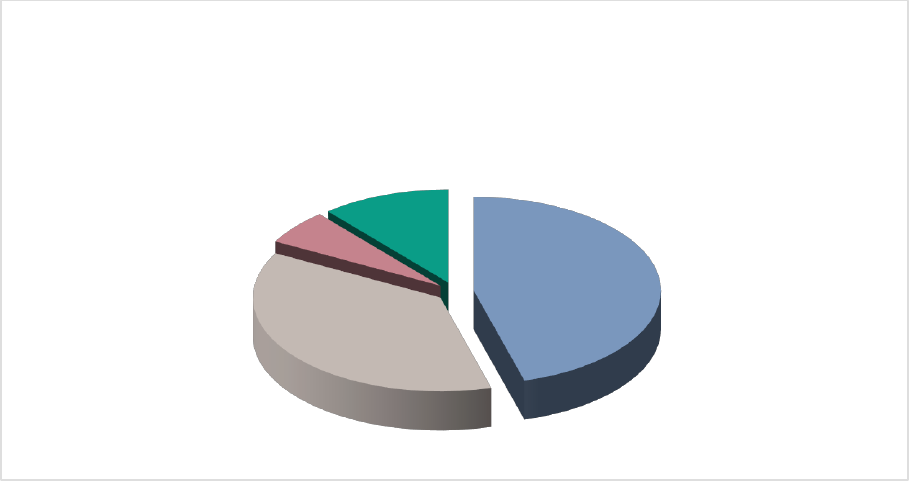

Breakdown of nTLDs by volume range

The graph below shows the breakdown of nTLDs by volume range. We can see that the

“Fewer than 5,000 names” bracket represents over 70% of the total, while the “More than

500,000” bracket represents only 1%, these proportions not having varied appreciably since

2014.

Community TLDs

44 777

.Brand

33 871

0%

.Brand open

71 247

0%

Geographic

961 018

4%

Generic

27 568 039

96%

Distribution of nTLDs by volume (2021)

37

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

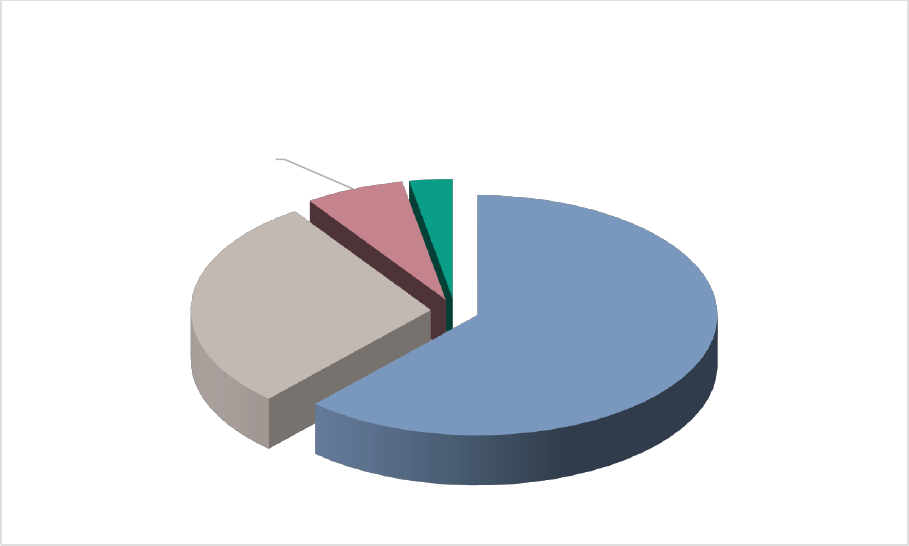

If we take into account ICANN’s fees ($25,000 minimum fixed cost) and the various costs

related to the management of a TLD (staff, back-end operator, promotion, etc.) and we

deduct a minimum average budget of $100,000 a year, it can be seen that the break-even

point for a TLD marketing its domain names at around $20 is 5,000 names (10,000 for a $10

fee close to that of .COM). It is therefore essential to analyse the distribution of nTLDs by type

and by volume bracket in order to evaluate the health of this segment.

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Breakdown of nTLDs by volume range

(2014-2021)

+ de 1 M 500,001 to 1 M 100,001 to 500,000 50,001 to 100,000

38

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

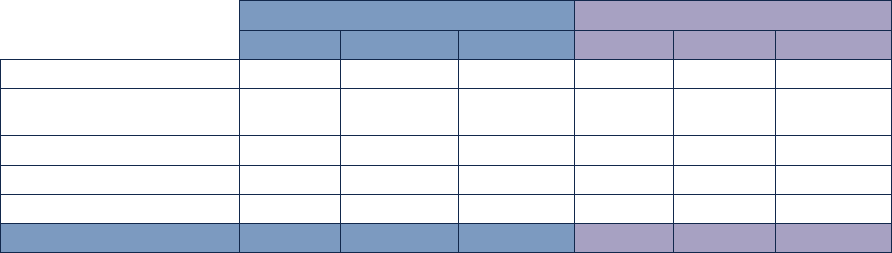

Volumes

COMM

GEO

GEN

OBR

BR

Total

%

2020

1 million or more

-

-

7

-

-

7

1%

1%

500,001 to 1 million

-

-

7

-

-

7

1%

0%

100,001 to 500,000

-

1

22

-

-

23

2%

2%

50,001 to 100,000

-

1

19

1

-

21

2%

2%

25,001 to 50,000

1

5

52

-

-

58

5%

4%

10,001 to 25,000

-

16

98

-

-

114

10%

10%

5,001 to 10,000

-

14

81

1

2

98

8%

8%

5,000 or fewer

11

25

240

-

553

829

72%

74%

TOTAL

12

62

526

2

555

1,157

% <10,000 names

92%

63%

61%

0%

100%

80%

% - Recap 2020

92%

60%

64%

0%

100%

82%

Breakdown of nTLDs by type and by volume range at 31 December 2021

Excluding .BRAND names which obey very different forms of logic and objectives, we obtain

276 TLDs of less than 5,000 names (or 46% of TLDs excluding .BRAND compared with 50% in

2018) and 372 TLDs with less than 10,000 names (62% of TLDs excluding .BRAND, compared with

66% in 2018).

The situation has therefore improved over time, but if we take 5,000 names as the “survival

threshold”, around 60% of nTLDs excluding .BRAND remain financially fragile. This is what lies

behind the move towards concentration, particularly marked in late 2020 and early 2021 with

the successive acquisitions of Afilias by Donuts and of Donuts by Ethos Capital.

On the one hand there are the smaller registries which are finding it difficult to make ends

meet, and on the other hand, holders of large portfolios of nTLDs which can make use of

economies of scale to significantly bring down operating costs. One of the keys to success

in this highly fragmented segment seems to be either holding several large nTLDs, or holding

a large number of small ones.

The pressure on costs (ICANN and others) will continue to intensify as time goes by. Registries

are placed in a particularly uncomfortable situation because they cannot develop their TLDs

without the requisite means, but these expenses may strangle them quite quickly in case of

failure of promotional campaigns.

Some have engaged in recent years in low-cost strategies that translate into exceptional

volumes for such “young” top-level domains. But “selling” a million domain names for

one cent each really only generates $10,000, which is one-tenth of the annual budget we

took as a working hypothesis, or the equivalent of 1,000 names sold for $10 each.

39

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

High volumes can therefore be indicators of success, but also the reflection of particularly

“kite-flying” strategies based on the assumption that holders attracted by very low prices at

the time of creation will agree to renew their names at more “normal” prices in the following

years. The case of .ICU, with its 3% renewal rate in 2021, is an almost exaggerated illustration

of this phenomenon.

These elements should encourage ICANN to rethink its pricing policy with regard to registries

of new TLDs, especially with regard to a second round. For most nTLDs excluding .BRAND

domains, its fixed fees of $25,000 constitute too heavy a burden, which prevents them from

developing and sometimes even causes them to suffocate by thus forming a barrier to entry

which benefits incumbents.

6.5. Change in retention rates per segment

Retention rates are a key element for analysing the success of a TLD and its chances of

lasting, the more so as a growing number of nTLDs rely on this parameter more than on their

create operations to ensure their survival.

Unsurprisingly, we see that the Generic TLDs have the lowest rate, with a deterioration in 2021

(38% compared to 43% in 2020 and 39% in 2019). But this rate remains a moving average.

The rate for open .BRANDs significantly declined in 2021 (from over 70% to 50%).

Geographic TLDs saw their retention rate stabilise in 2021 at close to 75%.

.BRANDs (not represented on the graph due to anomalies in the ICANN data for 2020) posted

a retention rate of 91% in 2021.

40

Afnic -The Global Domain Name Market in 2021

(The .COM rate is added as a comparison.)

The various nTLD segments therefore present strongly contrasting dynamics. In contrast