Treas.

HJ

4651

.A2

P94

1991

c. 2

General Explanations

of

the

President's Budget Proposals

Affecting Receipts

Department of the

Treasury

February

1991

\

z>

^

CONTENTS

Pag

Capital Gains Tax Rate Reduction for Individuals *

Family Savings Accounts 11

Penalty-Free IRA Withdrawals for First-Time Home Buyers 15

Permanent Research and Experimentation Tax Credit 17

Research and Experimentation Expense Allocation Rules 19

Enterprise Zone Tax Incentives 23

Solar and Geothermal Energy Credits 25

Targeted Jobs Tax Credit 27

Deduction for Special Needs Adoptions 29

Low-Income Housing Tax Credit 31

Health Insurance Deduction for the Self-Employed 33

Extend Tax Deadlines for Desert Shield/Storm Participants 35

Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) for State and Local Employees 37

Motor Fuels Excise Tax 39

Increase in IRS FY 1992 Enforcement Funding 41

Miscellaneous Proposals Affecting Receipts 43

^m 5030

CAPITAL GAINS TAX RATE REDUCTION FOR INDIVIDUALS

The Budget again includes a reduction of the capital gains tax rate for individuals on

long-term investments. The Budget provides for

a

10, 20,

or 30

percent exclusion for long-

term capital gains

on

assets held

by

individual taxpayers

for

one,

two or

three years,

respectively. The three-year holding period requirement will be phased in over three years.

In his State of the Union Address on January 29, 1991 the President asked Congressional

leaders

to

cooperate with the Administration

in a

study

led by

Federal Reserve Chairman

Alan Greenspan to sort out technical differences over the distributional and economic impacts

of a capital gains reduction.

A reduction in capital gains taxes should benefit all Americans by providing incentives

for saving and investment that would result in higher national output and more

jobs.

Current Law

Under current law, the full amount of capital gains income is generally taxable but the

rate

on

such gains

is

capped

at 28

percent. Capital gains

are

generally subject

to 15

percent

or 28

percent statutory

tax

rates. When capital gains taxes interact with other

provisions

in the

income

tax

code, however,

the

actual

tax

cost

of an

asset sale

can be

significantly higher. Interacting provisions include

the

requirement that itemized

deductions

for

medical

and

miscellaneous expenses exceed

a

percentage

of

adjusted gross

income,

the

phase-outs with increasing income

of IRA

deductions, passive activity loss

limitations,

and the phase-out of personal exemptions and the three percent floor

on

itemized

deductions enacted in 1990.

While the Tax Reform Act of 1986 eliminated the capital gains exclusion of prior law, it

did not eliminate the legal distinction between capital gains and ordinary income,

or

between

short-term

and

long-term capital gains. These distinctions currently serve

to

identify those

transactions eligible

for the 28

percent maximum rate

and

subject

to the

limitations

on

deduction

of

capital losses. Capital assets effectively include

all

property except

inventories

or

other items held for sale

in

the ordinary course of business and certain other

listed assets. Examples

of

capital assets include corporate stock,

a

home,

a

farm

or

business,

real estate,

and

antiques. Gains

or

losses from the sale

or

exchange

of

capital

assets held for one year or longer are classified as long-term capital gains or losses.

Individuals with capital losses exceeding capital gains may generally deduct up to $3,000

of such losses against ordinary income.

A net

capital loss

in

excess

of the

deduction

limitation

may be

carried forward. Special rules allow individuals

to

treat losses

of up to

$50,000 ($100,000

on a

joint return) with respect

to

stock

in

certain small business

corporations as ordinary losses.

-1-

-2-

Depreciation recapture rules recharacterize a portion of capital gains on depreciable

property as ordinary income. These rules vary for different types of depreciable property.

For personal property, all previously allowed depreciation not in excess of the realized

capital gain is generally recaptured as ordinary income. For real property using

straight-line depreciation, there is no depreciation recapture if the asset is held at least

one year. For real property acquired before 1987, generally only the excess of the

depreciation claimed in excess of straight-line depreciation is recaptured as ordinary

income. There are also recapture rules applicable to the disposition of depletable property

and to certain other assets.

Capital gains and losses are generally taken into account when "realized" upon the sale,

exchange, or other disposition of the asset. Certain dispositions of capital assets, such as

transfers by gift, are not generally realization events for income tax purposes. In general,

in the case of gifts the donor does not realize gain or loss, and the donor's basis in the

property carries over to the donee. In certain cases, such as the gift of a bond with

accrued market discount or of property that is subject to indebtedness in excess of the

donor's basis, the donor may recognize ordinary income upon making a gift. The capital gain

in a charitable contribution of appreciated property (other than tangible personal property

donated in 1991) is included as a preference item in calculating the alternative minimum tax.

Gain or loss is not realized on a transfer at death, and the beneficiary's basis in the

inherited asset is generally the fair market value of the asset at (or near) the date of

death.

Reasons for Change

Restoring a capital gains tax rate differential is important to restore economic growth

and competitive strength by promoting savings, entrepreneurial activity, and risky investment

in new products, processes, and industries. At the same time, investors should be encouraged

to extend their horizons and search for investments with longer-term growth potential. The

future competitiveness of this country requires a sustained flow of capital to innovative,

technologically advanced activities that may generate minimal short-term earnings but promise

strong future profitability. A preferential tax rate limited to longer-term commitments of

capital will encourage business investment patterns that favor innovation and long-term

growth over short-term profitability. The resulting increase in national output will benefit

all Americans by providing jobs and raising living standards. In addition to the improve-

ments in productivity and economic growth, a lower rate on long-term capital gains will also

improve the fairness of the individual income tax by providing a rough adjustment for the

taxation of inflationary gains that do not represent any increase in real income.

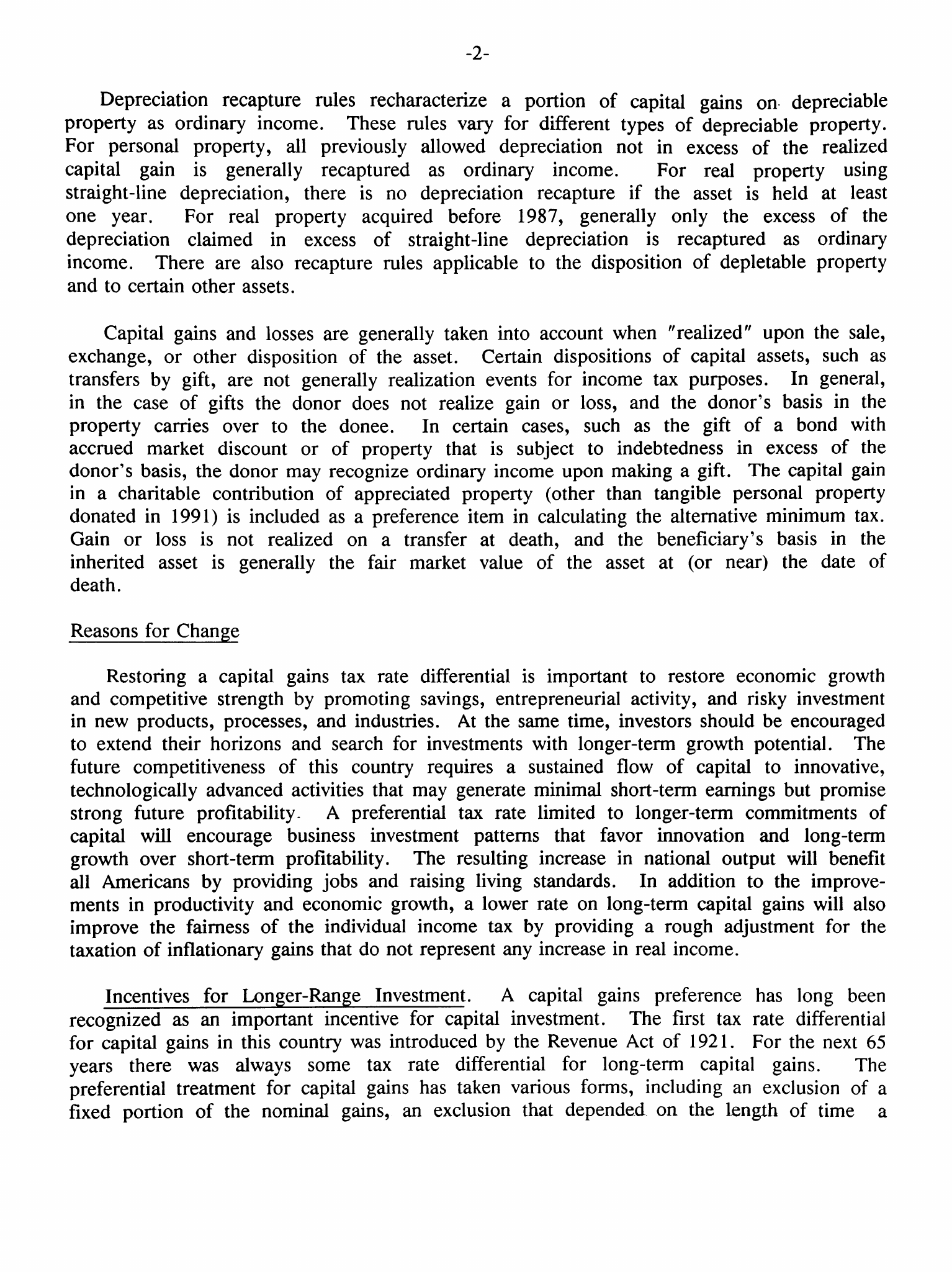

Incentives for Longer-Range Investment. A capital gains preference has long been

recognized as an important incentive for capital investment. The first tax rate differential

for capital gains in this country was introduced by the Revenue Act of 1921. For the next 65

years there was always some tax rate differential for long-term capital gains. The

preferential treatment for capital gains has taken various forms, including an exclusion of a

fixed portion of the nominal gains, an exclusion that depended on the length of time a

-3-

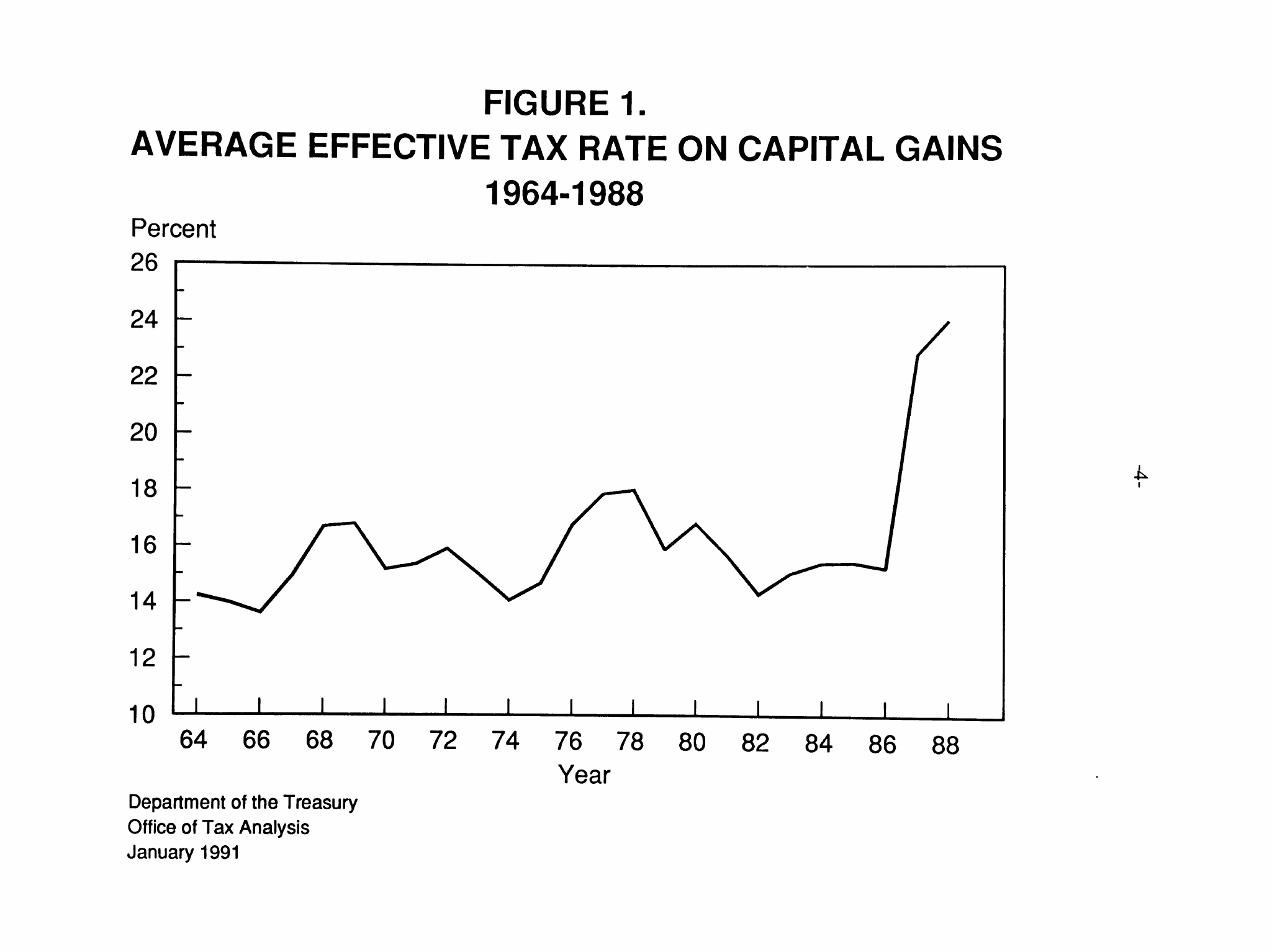

taxpayer held an asset, and a special maximum tax rate for capital gains. But at no time

between 1921 and 1987 were long-term capital gains ever taxed at the same rates as ordinary

income. In 1990, Congress set the maximum marginal tax rate on capital gains at 28 percent,

or three percentage points below the maximum marginal rate on ordinary income. Nevertheless,

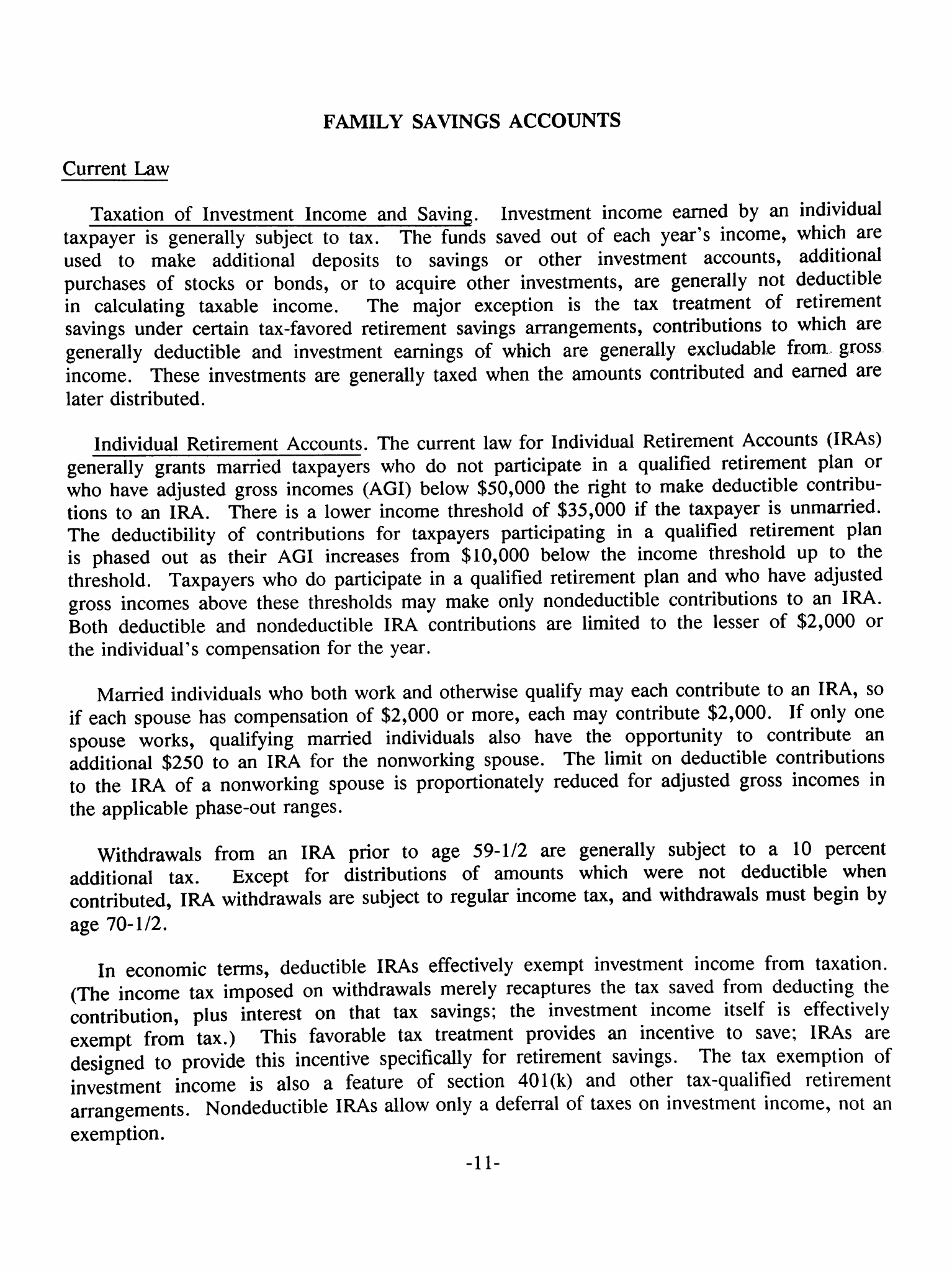

as shown in Figure 1, the average effective tax rate on realized capital gains is currently

substantially higher than it has been in the past.

By eliminating the capital gains exclusion and lowering tax rates on ordinary income, the

1986 Act increased the incentives for short-term trading of capital assets. This occurred

because the tax rate on long-term capital gains was increased while the tax rate on

short-term capital gains was reduced. By providing for a sliding scale exclusion that

provides full benefits only for investments held at least three years after a phase-in

period, the Budget proposal would increase the incentive for longer term investing.

The Cost of Capital and International Competitiveness. The capital gains tax is an

important component of the cost of capital, which measures the pre-tax rate of return

required to induce businesses to undertake new investment. Evidence suggests that the cost

of capital in the United States is higher than in many other industrial nations. While not

solely responsible for the higher cost of capital, high capital gains tax rates hurt the

ability of U.S. firms to obtain the capital needed to remain competitive. By reducing the

cost of capital, a reduction in the capital gains tax rate would stimulate productive

investment and create new jobs and growth.

Our major trading partners already recognize the economic importance of low tax rates on

capital gains. Virtually all other major industrial nations provide much lower tax rates on

capital gains or do not tax capital gains at all. Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the

Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, among others, all treat capital gains preferentially.

The Lock-In Effect. Under a tax system in which capital gains are not taxed until

realized by the taxpayer, a substantial tax on capital gains tends to lock taxpayers into

their existing investments. Many taxpayers who would otherwise prefer to sell their assets

to acquire new and better investments may instead continue to hold onto the assets rather

than pay the current high capital gains tax on their accrued gains.

This lock-in effect of capital gains taxation has three adverse effects. First, it

produces a misallocation of the nation's capital stock and entrepreneurial talent because it

distorts the investment decisions that would be made in the absence of the capital gains tax.

For example, the lock-in effect reduces the ability of entrepreneurs to withdraw from an

enterprise and use the funds to start new ventures. Productivity in the economy suffers

because entrepreneurs are less likely to move capital to where it can be most productive, and

because capital may be used in a less productive fashion than if it were transferred to

other, more efficient, enterprises. These effects can be especially critical for smaller

firms which may not have good access to capital markets and where ownership and operation

frequently go together. Second, the lock-in effect produces distortions in the investment

portfolios of individual taxpayers. For example, some individual investors may be induced to

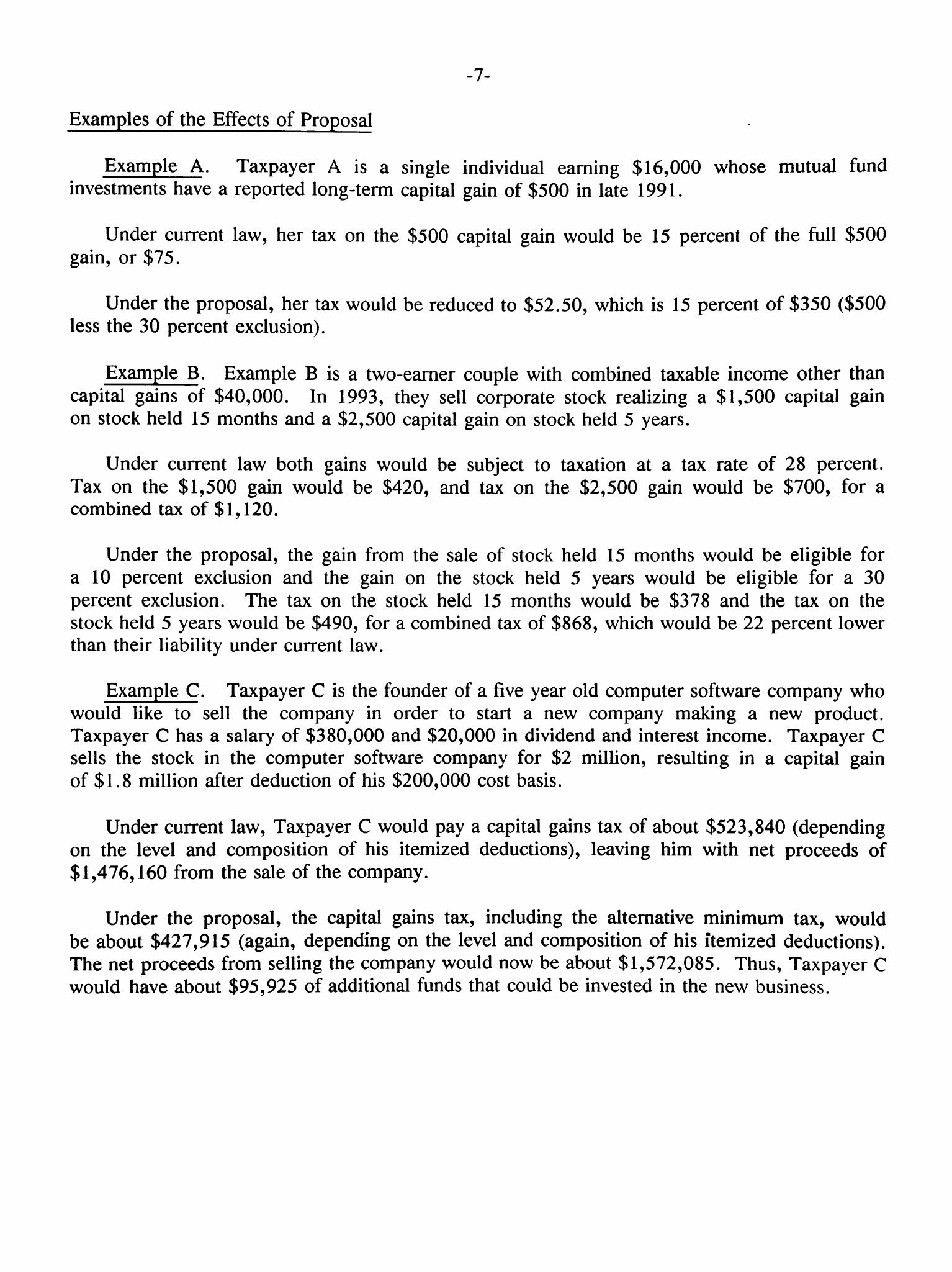

FIGURE 1.

AVERAGE EFFECTIVE TAX RATE ON CAPITAL GAINS

1964-1988

Percent

4

64 66 68 70 72 74

Department of the Treasury

Office of

Tax

Analysis

January

1991

76 78 80

Year

82 84 86 88

-5-

assume more risk or hold a different mix of assets than they desire because they are

reluctant to sell appreciated investments to diversify their portfolios. Third, the lock-in

effect reduces government receipts. To the extent that taxpayers defer sales of existing

investments, or hold onto investments until death, taxes that might otherwise have been paid

are deferred or avoided altogether. Therefore, individual investors, the government, and

other taxpayers lose from the lock-in effect. The investor is discouraged from pursuing more

attractive investments and the government loses revenue.

Substantial evidence from more than a dozen studies demonstrates that high capital gains

tax rates in previous years produced significant lock-in effects. The importance of the

lock-in effect may also be demonstrated by the fact that realized capital gains were 16

percent lower under the high tax rates in 1987 than under the lower rates in 1985, even

though stock prices had risen by approximately 50 percent over this period. The high tax

rates on capital gains under current law imply that the lock-in effect is greater than at any

prior time.

Penalty on High-Risk Investments. Full taxation of capital gains, in combination with

limited deductibility of capital losses, discourages risk taking. It therefore impedes

investment in emerging high-technology and other high-risk firms. While many investors are

willing to take risks in anticipation of an adequate return, fewer are willing to contribute

"venture capital" if a significant fraction of the increased reward will be used merely to

satisfy higher tax liabilities. A tax system that imposes a high tax rate on gains from the

investment reduces the attractiveness of risky investments, and may result in many worthwhile

projects not being undertaken.

In particular, it is inherently more risky to start new firms and invest in new products

and processes than to make incremental investments in existing firms and products. It is

therefore the most dynamic and innovative firms and entrepreneurs that are the most

disadvantaged by high capital gain tax rates that penalize risk taking. Such firms have

traditionally been contributors to America's edge in international competition and have

provided an important source of new jobs.

Double Tax on Corporate Stock Investment. Under the U.S. income tax system, income

earned on investments in corporate stock is generally subjected to two layers of tax. Income

on corporate investments is taxed first at the corporate level at a rate of 34 percent.

Corporate income is taxed a second time at the individual level in the form of taxes on

capital gains and dividends at rates ranging from 15 to 31 percent. The combination of

corporate and individual income taxes thus can produce effective tax rates that are

substantially greater than individual income tax rates alone. To the extent the return to

the investor is obtained through appreciation in the value of the stock (rather than through

dividend

income),

a reduction in capital gains tax rates provides a form of relief from this

double taxation of corporate income. While a lower capital gains tax rate reduces the cost

of capital for both corporate and noncorporate business, the greater liquidity of shares in

publicly-traded companies suggests that the overall effect would be to reduce the bias

towards noncorporate business that results from our dual-level tax system.

-6-

Description of Proposal

General Rule. The capital gains tax rate would be reduced by means of a sliding-scale

exclusion. Individuals would be allowed to exclude a percentage of the capital gain realized

upon the disposition of qualified capital assets, and would apply their current marginal rate

on capital gains (either 15 or 28 percent) to the reduced amount of taxable gain. The amount

of the exclusion would depend on the holding period of the assets. Assets held three years

or more would qualify for an exclusion of 30 percent. Assets held at least two years but

less than three years would qualify for a 20 percent exclusion. Assets held at least one

year but less than two years would qualify for a 10 percent exclusion. For example,

individuals subject to a 28 percent tax on capital gain (i.e., taxpayers in the 28 and 31

percent tax brackets for ordinary income) would pay rates of

25.2,

22.4, and 19.6 percent for

assets held one, two, or three years, respectively. The corresponding figures for

individuals subject to a 15 percent rate would be 13.5, 12.0, and 10.5 percent.

Qualified assets would generally be defined as any assets qualifying as capital assets

under current law and satisfying the holding period requirements, except for collectibles.

Collectibles are assets such as works of art, antiques, precious metals, gems, alcoholic

beverages,

and stamps and coins. Assets eligible for the exclusion would include, for

example, corporate stock, manufacturing and farm equipment, a home, an apartment building, a

stand of timber, or a family farm.

Phase-in Rules and Effective Dates. The proposal would be effective generally for

dispositions of qualified assets after the date of enactment. For the balance of 1991, the

full 30 percent exclusion would apply to assets held at least one year. For dispositions of

assets in 1992, assets would be required to have been held for two years or more to be

eligible for the 30 percent exclusion, and at least one year but less than two years to be

eligible for the 20 percent exclusion. For dispositions of assets in 1993 and thereafter,

assets would be required to have been held at least three years to be eligible for the 30

percent exclusion, at least two years but less than three years for the 20 percent exclusion

and at least one year but less than two years for the 10 percent exclusion.

Additional Provisions. In order to prevent taxpayers from benefitting from the exclusion

provision for depreciation deductions that have already been claimed in prior years, the

depreciation recapture rules would be expanded to recapture all prior depreciation

deductions. All taxpayers would be able to benefit from the proposed exclusion to the extent

that a depreciable asset has increased in value above its unadjusted basis. The excluded

portion of capital gains would be added back when calculating income under the alternative

minimum tax, however, the special rule relating to contributions of tangible personal

property in 1991 would not be modified. Installment sale payments received after the

effective date will be eligible for the exclusion without regard to the date the sale

actually took place. For purposes of the investment interest limitation, only the net

capital gain after subtracting the excluded amount would be included in investment income.

The 28 percent limitation on capital gains not eligible for the exclusions would be retained.

-7-

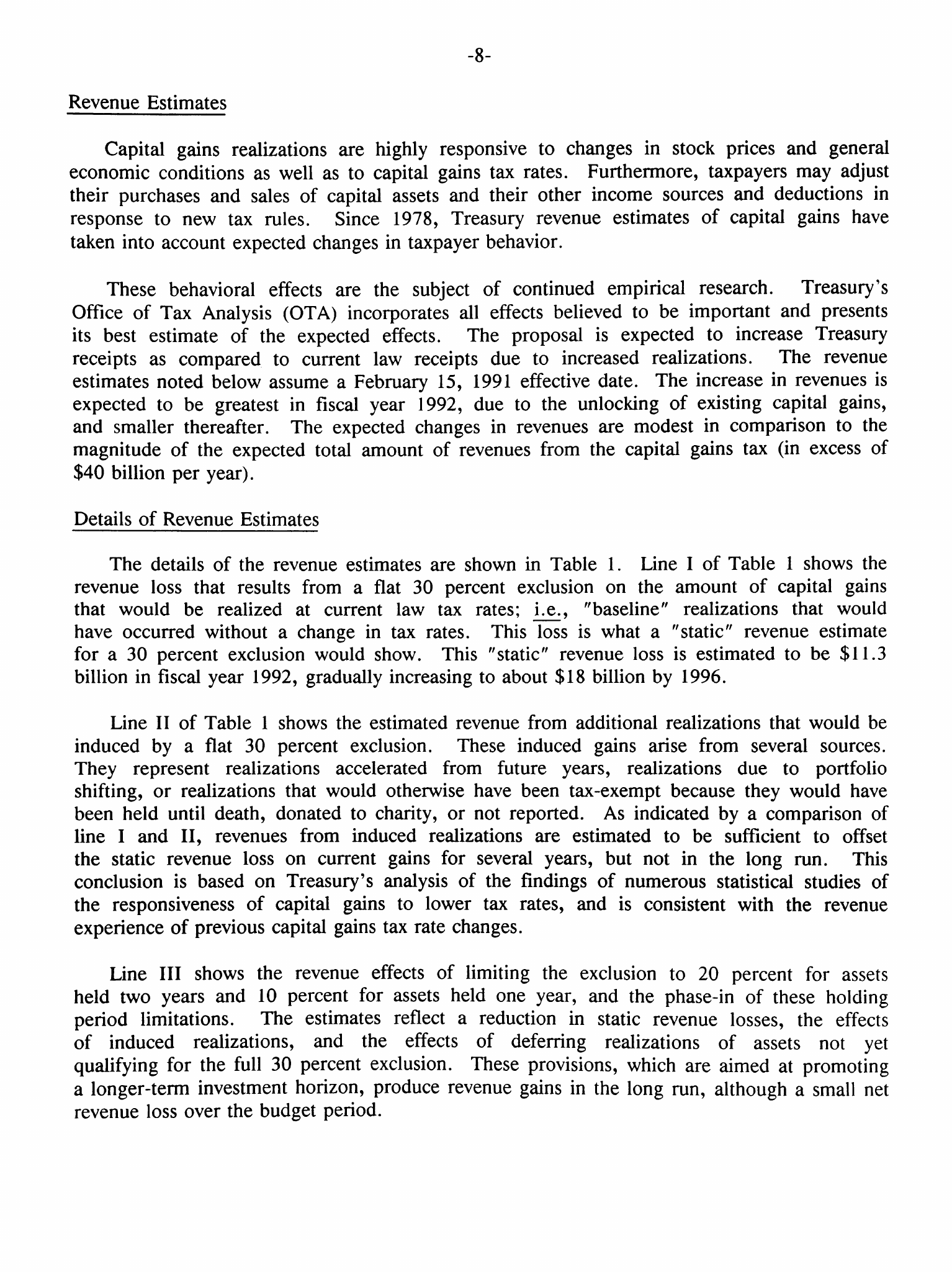

Examples of the Effects of Proposal

Example A. Taxpayer A is a single individual earning $16,000 whose mutual fund

investments have a reported long-term capital gain of $500 in late 1991.

Under current law, her tax on the $500 capital gain would be 15 percent of the full $500

gain, or $75.

Under the proposal, her tax would be reduced to $52.50, which is 15 percent of $350 ($500

less the 30 percent

exclusion).

Example B. Example B is a two-earner couple with combined taxable income other than

capital gains of $40,000. In 1993, they sell corporate stock realizing a $1,500 capital gain

on stock held 15 months and a $2,500 capital gain on stock held 5 years.

Under current law both gains would be subject to taxation at a tax rate of 28 percent.

Tax on the $1,500 gain would be

$420,

and tax on the $2,500 gain would be

$700,

for a

combined tax of $1,120.

Under the proposal, the gain from the sale of stock held 15 months would be eligible for

a 10 percent exclusion and the gain on the stock held 5 years would be eligible for a 30

percent exclusion. The tax on the stock held 15 months would be $378 and the tax on the

stock held 5 years would be

$490,

for a combined tax of

$868,

which would be 22 percent lower

than their liability under current law.

Example C. Taxpayer C is the founder of a five year old computer software company who

would like to sell the company in order to start a new company making a new product.

Taxpayer C has a salary of $380,000 and $20,000 in dividend and interest income. Taxpayer C

sells the stock in the computer software company for $2 million, resulting in a capital gain

of $1.8 million after deduction of his $200,000 cost basis.

Under current law, Taxpayer C would pay a capital gains tax of about $523,840 (depending

on the level and composition of his itemized

deductions),

leaving him with net proceeds of

$1,476,160 from the sale of the company.

Under the proposal, the capital gains tax, including the alternative minimum tax, would

be about $427,915 (again, depending on the level and composition of his itemized

deductions).

The net proceeds from selling the company would now be about $1,572,085. Thus, Taxpayer C

would have about $95,925 of additional funds that could be invested in the new business.

-8-

Revenue Estimates

Capital gains realizations are highly responsive to changes in stock prices and general

economic conditions as well as to capital gains tax rates. Furthermore, taxpayers may adjust

their purchases and sales of capital assets and their other income sources and deductions in

response to new tax rules. Since 1978, Treasury revenue estimates of capital gains have

taken into account expected changes in taxpayer behavior.

These behavioral effects are the subject of continued empirical research. Treasury's

Office of Tax Analysis (OTA) incorporates all effects believed to be important and presents

its best estimate of the expected effects. The proposal is expected to increase Treasury

receipts as compared to current law receipts due to increased realizations. The revenue

estimates noted below assume a February 15, 1991 effective date. The increase in revenues is

expected to be greatest in fiscal year 1992, due to the unlocking of existing capital gains,

and smaller thereafter. The expected changes in revenues are modest in comparison to the

magnitude of the expected total amount of revenues from the capital gains tax (in excess of

$40 billion per

year).

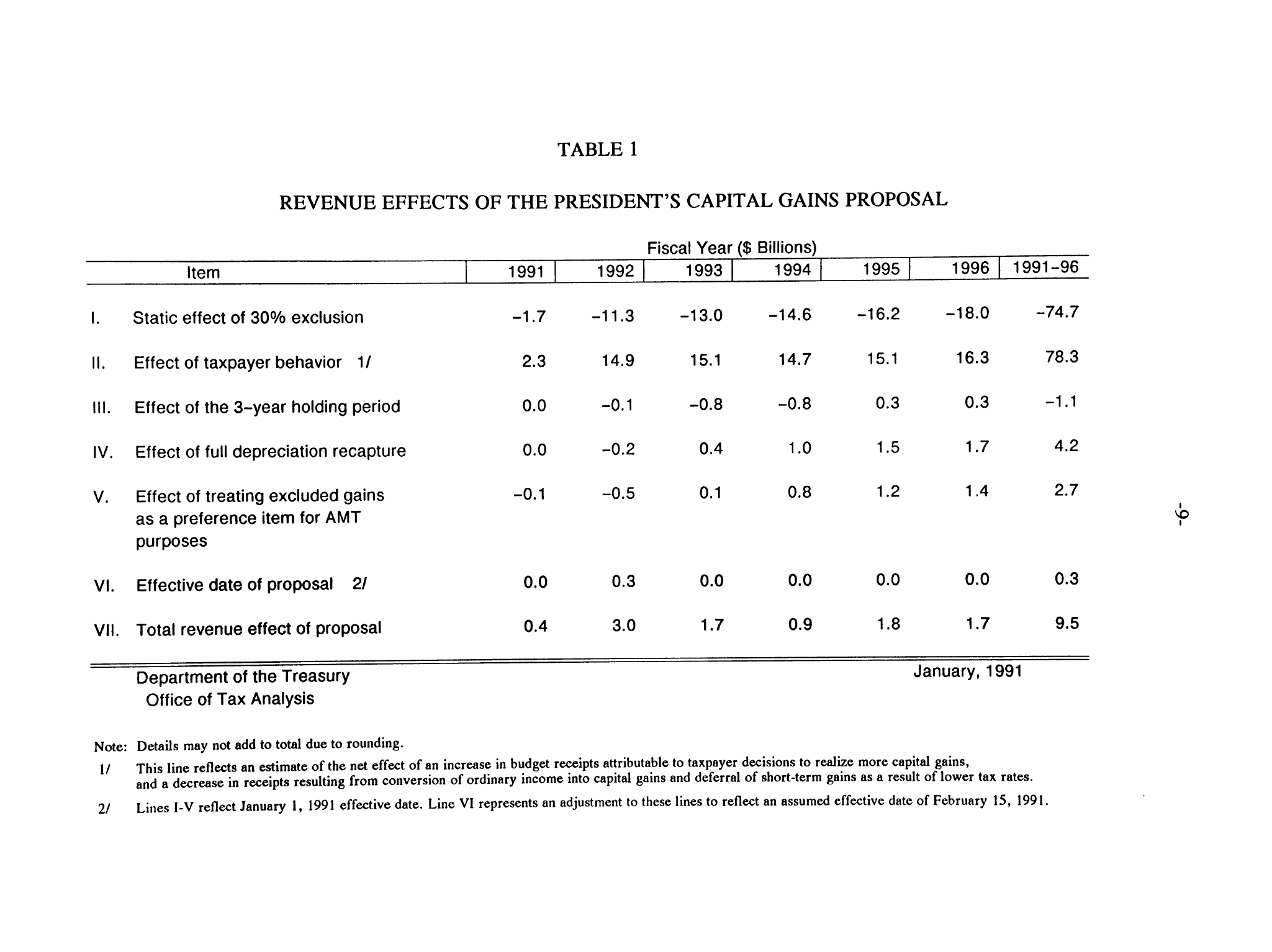

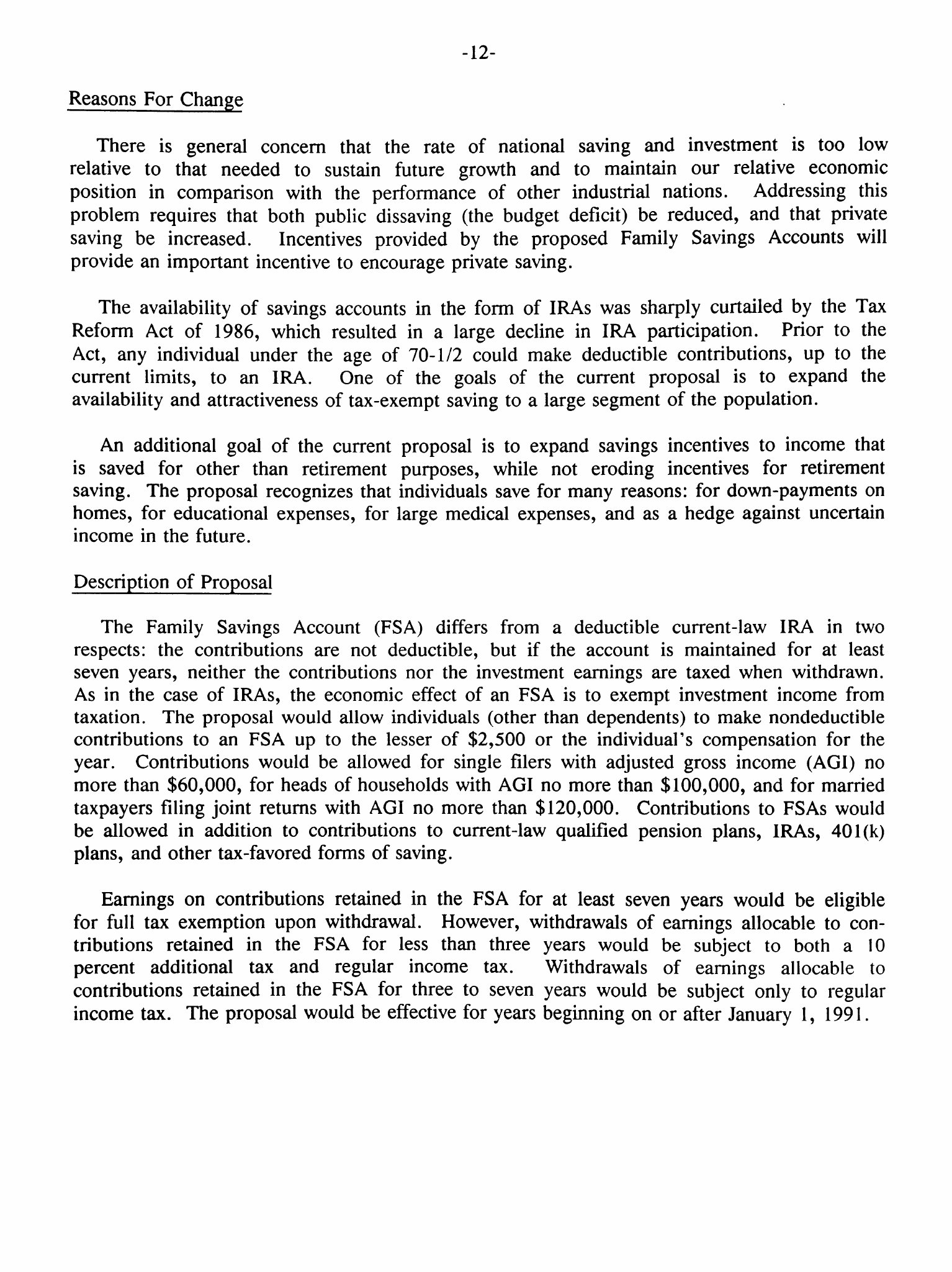

Details of Revenue Estimates

The details of the revenue estimates are shown in Table 1. Line I of Table 1 shows the

revenue loss that results from a flat 30 percent exclusion on the amount of capital gains

that would be realized at current law tax rates; Le., "baseline" realizations that would

have occurred without a change in tax rates. This loss is what a "static" revenue estimate

for a 30 percent exclusion would show. This "static" revenue loss is estimated to be $11.3

billion in fiscal year 1992, gradually increasing to about $18 billion by 1996.

Line II of Table 1 shows the estimated revenue from additional realizations that would be

induced by a flat 30 percent exclusion. These induced gains arise from several sources.

They represent realizations accelerated from future years, realizations due to portfolio

shifting, or realizations that would otherwise have been tax-exempt because they would have

been held until death, donated to charity, or not reported. As indicated by a comparison of

line I and II, revenues from induced realizations are estimated to be sufficient to offset

the static revenue loss on current gains for several years, but not in the long run. This

conclusion is based on Treasury's analysis of the findings of numerous statistical studies of

the responsiveness of capital gains to lower tax rates, and is consistent with the revenue

experience of previous capital gains tax rate changes.

Line III shows the revenue effects of limiting the exclusion to 20 percent for assets

held two years and 10 percent for assets held one year, and the phase-in of these holding

period limitations. The estimates reflect a reduction in static revenue losses, the effects

of induced realizations, and the effects of deferring realizations of assets not yet

qualifying for the full 30 percent exclusion. These provisions, which are aimed at promoting

a longer-term investment horizon, produce revenue gains in the long run, although a small net

revenue loss over the budget period.

TABLE

1

REVENUE EFFECTS OF THE PRESIDENT'S CAPITAL

GAINS

PROPOSAL

Item

1991

Fiscal Year ($ Billions)

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996 1991-96

Static effect of 30% exclusion

11.

Effect of taxpayer behavior

1

/

III. Effect of the 3-year holding period

IV. Effect of full depreciation recapture

V. Effect of treating excluded gains

as

a

preference item for AMT

purposes

1.7

2.3

0.0

0.0

0.1

-11.3

14.9

-0.1

-0.2

-0.5

-13.0

15.1

-0.8

0.4

0.1

-14.6

14.7

-0.8

1.0

0.8

-16.2

15.1

0.3

1.5

1.2

-18.0

16.3

0.3

1.7

1.4

-74.7

78.3

-1.1

4.2

2.7

i

VI.

Effective date of proposal

2/

0.0

0.3

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.3

VII.

Total revenue effect of proposal

0.4

3.0

1.7

0.9

1.8

1.7

9.5

Department of the Treasury

Office of Tax Analysis

January, 1991

Note: Details

may

not add to total due to rounding.

1/ This line reflects

an

estimate of the net effect of an increase in budget receipts attributable to taxpayer decisions to realize more capital gains,

and

a

decrease in receipts resulting from conversion of ordinary income into capital gains and deferral of short-term gains as

a

result of lower tax rates.

2/ Lines I-V reflect January 1, 1991 effective date. Line VI represents an adjustment to these lines to reflect an assumed effective date of February 15, 1991

-10-

Lines IV and V show the revenue effects of expanded depreciation recapture and treating

excluded capital gains as a preference item for purposes of the alternative minimum tax.

These two provisions are critical to turning the proposal from one that would otherwise

probably lose revenue in the long run to one that is revenue-raising even beyond the budget

period. Over the budget period, these two provisions raise $6.9 billion in revenue. The

full depreciation recapture proposal means that if a depreciable asset is sold, the exclusion

will apply only to the amount by which the current selling price is higher than the original

cost. Treating excluded gains as a preference item for purposes of the alternative minimum

tax primarily affects high-income individuals and raises $2.7 billion over the budget period.

Line VI shows the revenue effect of making the effective date of the proposal February 15,

1991.

The total revenue effect of the proposal is shown in line VII. The proposal is expected

to raise revenue in every year and $9.5 billion over the budget period. Treasury's estimates

indicate that the Administration proposal would produce increased revenues not only through-

out the budget period, but for the foreseeable future.*

These estimates do not include the effects of potential increases in long-run economic

growth expected from a lower capital gains tax rate. This conforms to the standard budget

and revenue estimating practice of assuming that the macroeconomic effects of revenue and

spending proposals are already included in the economic forecast.

Because the methodological differences between OTA, Congressional estimators, and outside

experts have not yet been resolved, the Budget reflects the deficit impact of the

Administration's Pay-As-You-Go proposals with the Administration's estimates and with a

zero (neutral) entry for capital gains rate reduction (see Table II-8, Part One, p. 18,

of the Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year

1992).

FAMILY SAVINGS ACCOUNTS

Current Law

Taxation of Investment Income and Saving. Investment income earned by an individual

taxpayer is generally subject

to

tax. The funds saved out of each year's income, which

are

used

to

make additional deposits

to

savings

or

other investment accounts, additional

purchases

of

stocks

or

bonds,

or to

acquire other investments, are generally not deductible

in calculating taxable income.

The

major exception

is the tax

treatment

of

retirement

savings under certain tax-favored retirement savings arrangements, contributions

to

which are

generally deductible

and

investment earnings

of

which are generally excludable from gross

income. These investments are generally taxed when the amounts contributed and earned are

later distributed.

Individual Retirement Accounts. The current law for Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs)

generally grants married taxpayers

who do

not participate

in a

qualified retirement plan

or

who have adjusted gross incomes (AGI) below $50,000 the right to make deductible contribu-

tions to

an

IRA. There is

a

lower income threshold of $35,000 if the taxpayer is unmarried.

The deductibility

of

contributions for taxpayers participating

in a

qualified retirement plan

is phased out

as

their AGI increases from $10,000 below the income threshold

up to the

threshold. Taxpayers who

do

participate in

a

qualified retirement plan and who have adjusted

gross incomes above these thresholds may make only nondeductible contributions to

an

IRA.

Both deductible

and

nondeductible

IRA

contributions are limited

to

the lesser

of

$2,000

or

the individual's compensation for the year.

Married individuals who both work and otherwise qualify may each contribute to an IRA, so

if each spouse has compensation of $2,000 or more, each may contribute

$2,000.

If only one

spouse works, qualifying married individuals also have

the

opportunity

to

contribute

an

additional $250 to

an

IRA for the nonworking spouse. The limit

on

deductible contributions

to the IRA of

a

nonworking spouse is proportionately reduced for adjusted gross incomes

in

the applicable phase-out ranges.

Withdrawals from an IRA prior to age 59-1/2 are generally subject to a 10 percent

additional tax. Except

for

distributions

of

amounts which were

not

deductible when

contributed, IRA withdrawals are subject to regular income

tax,

and withdrawals must begin

by

age

70-1/2.

In economic terms, deductible IRAs effectively exempt investment income from taxation.

(The income tax imposed

on

withdrawals merely recaptures the tax saved from deducting the

contribution, plus interest

on

that

tax

savings;

the

investment income itself

is

effectively

exempt from tax.) This favorable

tax

treatment provides

an

incentive

to

save; IRAs

are

designed

to

provide this incentive specifically for retirement savings. The tax exemption

of

investment income

is

also

a

feature

of

section 401(k)

and

other tax-qualified retirement

arrangements. Nondeductible IRAs allow only

a

deferral of taxes on investment income, not

an

exemption.

-11-

-12-

Reasons For Change

There is general concern that the rate of national saving and investment is too low

relative to that needed to sustain future growth and to maintain our relative economic

position in comparison with the performance of other industrial nations. Addressing this

problem requires that both public dissaving (the budget deficit) be reduced, and that private

saving be increased. Incentives provided by the proposed Family Savings Accounts will

provide an important incentive to encourage private saving.

The availability of savings accounts in the form of IRAs was sharply curtailed by the Tax

Reform Act of 1986, which resulted in a large decline in IRA participation. Prior to the

Act, any individual under the age of 70-1/2 could make deductible contributions, up to the

current limits, to an IRA. One of the goals of the current proposal is to expand the

availability and attractiveness of tax-exempt saving to a large segment of the population.

An additional goal of the current proposal is to expand savings incentives to income that

is saved for other than retirement purposes, while not eroding incentives for retirement

saving. The proposal recognizes that individuals save for many reasons: for down-payments on

homes,

for educational expenses, for large medical expenses, and as a hedge against uncertain

income in the future.

Description of Proposal

The Family Savings Account (FSA) differs from a deductible current-law IRA in two

respects:

the contributions are not deductible, but if the account is maintained for at least

seven years, neither the contributions nor the investment earnings are taxed when withdrawn.

As in the case of IRAs, the economic effect of an FSA is to exempt investment income from

taxation. The proposal would allow individuals (other than dependents) to make nondeductible

contributions to an FSA up to the lesser of $2,500 or the individual's compensation for the

year.

Contributions would be allowed for single filers with adjusted gross income (AGI) no

more than $60,000, for heads of households with AGI no more than $100,000, and for married

taxpayers

filing

joint returns with AGI no more than $120,000. Contributions to FSAs would

be allowed in addition to contributions to current-law qualified pension plans, IRAs, 401(k)

plans,

and other tax-favored forms of saving.

Earnings on contributions retained in the FSA for at least seven years would be eligible

for full tax exemption upon withdrawal. However, withdrawals of earnings allocable to con-

tributions retained in the FSA for less than three years would be subject to both a 10

percent additional tax and regular income tax. Withdrawals of earnings allocable to

contributions retained in the FSA for three to seven years would be subject only to regular

income tax. The proposal would be effective for years beginning on or after January 1, 1991.

-13-

Effects of Proposal

The proposal would increase the total amount of individual saving that can earn tax-free

investment income. Generally, individuals would be able to contribute to FSAs, IRAs, 401(k)

plans,

and similar tax-favored plans, and would receive tax exemption on the investment

income from each source.

The ability to contribute to an FSA would significantly raise the total amount of

allowable contributions to tax-favored savings accounts. The contribution limit is $5,000

for joint return filers as compared to the $4,000 IRA limit for a working couple. These

higher total contribution limits for FSAs will provide additional marginal incentives for

personal saving. The higher eligibility limits on FSAs also expand the incentives to more

taxpayers.

Despite the difference in structure, the value of the tax benefits in present value of an

FSA per dollar of contribution is equivalent in terms of its tax treatment to the value of

current-law deductible IRAs, assuming that tax rates are constant over time. Both FSAs and

deductible IRAs effectively exempt all investment income from tax. The contributions to FSAs

are not deductible, but the income tax imposed on withdrawals from an IRA effectively offsets

the tax savings from the deduction of the contribution (plus interest on the tax

savings).

Individuals who expect higher tax rates when the funds are withdrawn would generally prefer

the tax treatment offered in an FSA to that in an IRA. Conversely, individuals who expect

lower future tax rates would generally prefer an IRA as a vehicle for retirement savings.

However, the FSA offers more flexibility, because full tax benefits are available seven years

after contribution and the account need not be held until retirement. This gives individuals

an added degree of liquidity.

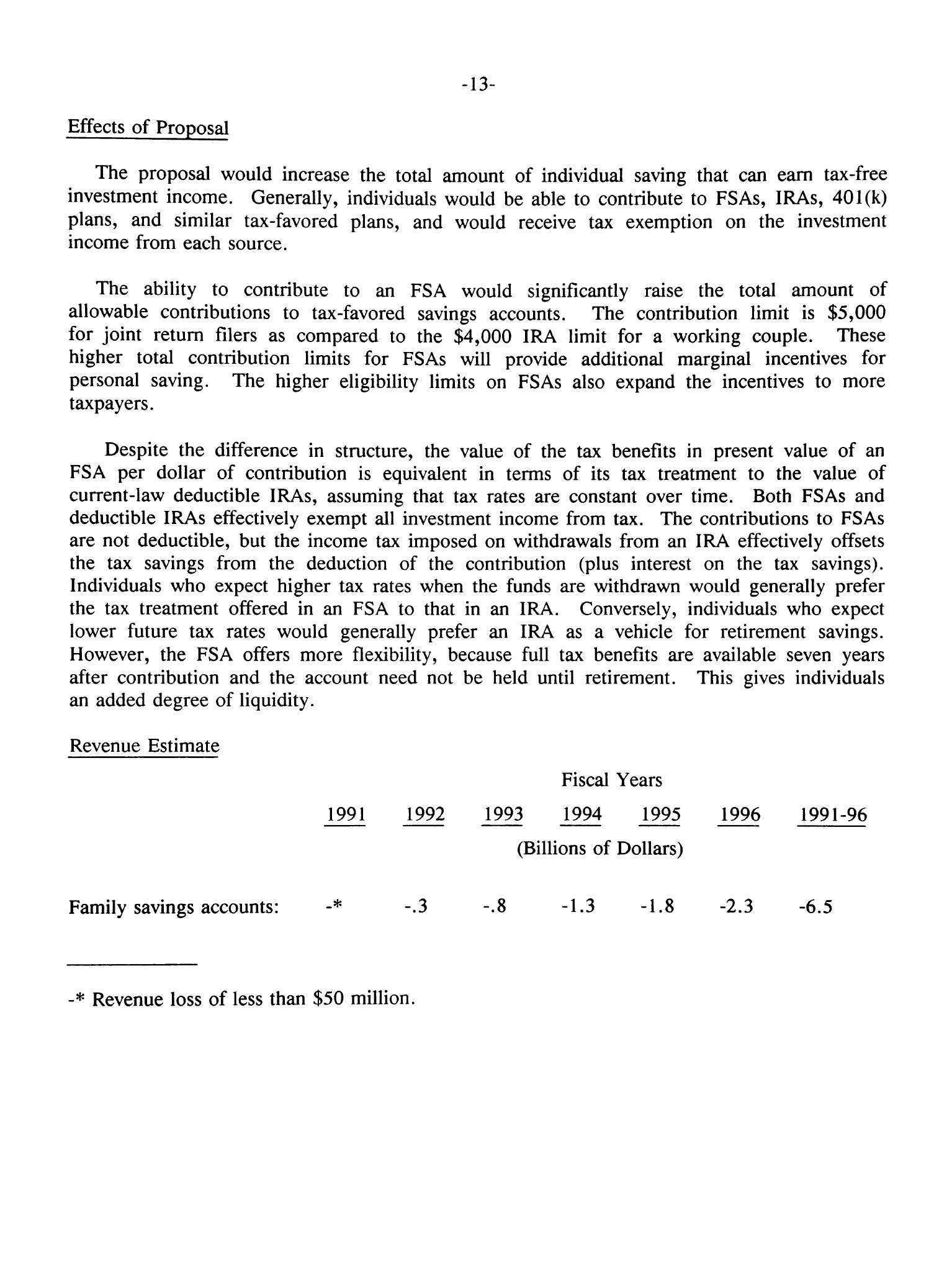

Revenue Estimate

Fiscal Years

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1991-96

(Billions of Dollars)

Family savings accounts: -* -.3 -.8 -1.3 -1.8 -2.3 -6.5

-* Revenue loss of less than $50 million.

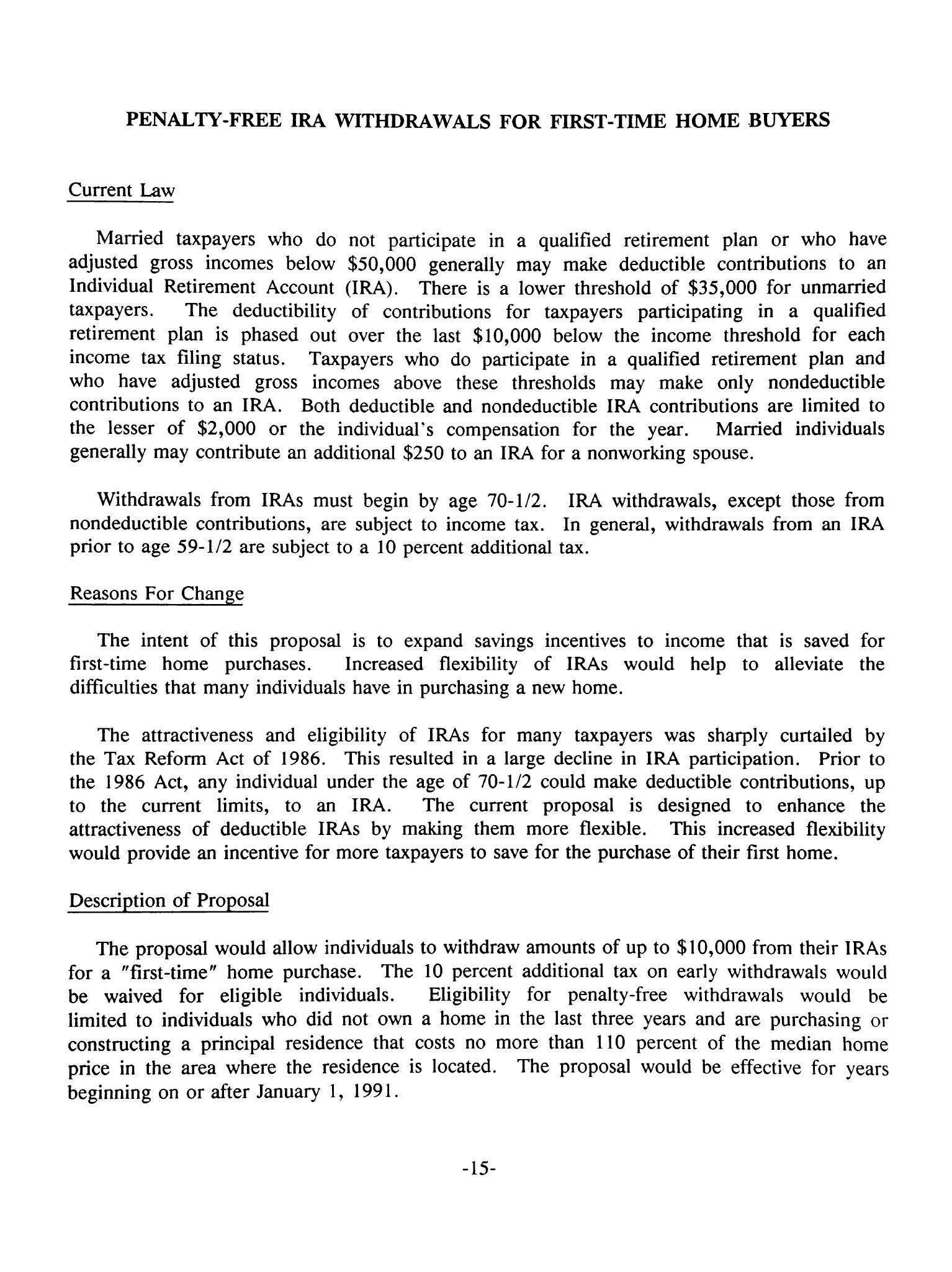

PENALTY-FREE IRA WITHDRAWALS FOR FIRST-TIME HOME BUYERS

Current Law

Married taxpayers who do not participate in a qualified retirement plan or who have

adjusted gross incomes below $50,000 generally

may

make deductible contributions

to an

Individual Retirement Account

(IRA).

There is

a

lower threshold

of

$35,000 for unmarried

taxpayers.

The

deductibility

of

contributions

for

taxpayers participating

in a

qualified

retirement plan

is

phased

out

over the last $10,000 below the income threshold

for

each

income tax filing status. Taxpayers

who do

participate

in a

qualified retirement plan

and

who have adjusted gross incomes above these thresholds

may

make only nondeductible

contributions to

an

IRA. Both deductible and nondeductible IRA contributions are limited

to

the lesser

of

$2,000

or the

individual's compensation

for the

year. Married individuals

generally may contribute an additional $250 to an IRA for

a

nonworking spouse.

Withdrawals from IRAs must begin by age 70-1/2. IRA withdrawals, except those from

nondeductible contributions, are subject to income tax.

In

general, withdrawals from

an IRA

prior to age 59-1/2 are subject to

a

10 percent additional tax.

Reasons For Change

The intent of this proposal is to expand savings incentives to income that is saved for

first-time home purchases. Increased flexibility

of

IRAs would help

to

alleviate

the

difficulties that many individuals have in purchasing

a

new home.

The attractiveness and eligibility of IRAs for many taxpayers was sharply curtailed by

the Tax Reform Act

of

1986. This resulted in

a

large decline in IRA participation. Prior

to

the 1986 Act, any individual under the age of 70-1/2 could make deductible contributions,

up

to

the

current limits,

to an IRA. The

current proposal

is

designed

to

enhance

the

attractiveness

of

deductible IRAs

by

making them more flexible. This increased flexibility

would provide an incentive for more taxpayers to save for the purchase of their

first

home.

Description of Proposal

The proposal would allow individuals to withdraw amounts of up to $10,000 from their IRAs

for

a

"first-time" home purchase.

The 10

percent additional tax

on

early withdrawals would

be waived

for

eligible individuals. Eligibility

for

penalty-free withdrawals would

be

limited to individuals who did not own

a

home in the last three years and are purchasing

or

constructing

a

principal residence that costs

no

more than 110 percent

of

the median home

price

in

the area where the residence is located. The proposal would

be

effective for years

beginning on or after January 1, 1991.

-15-

-16-

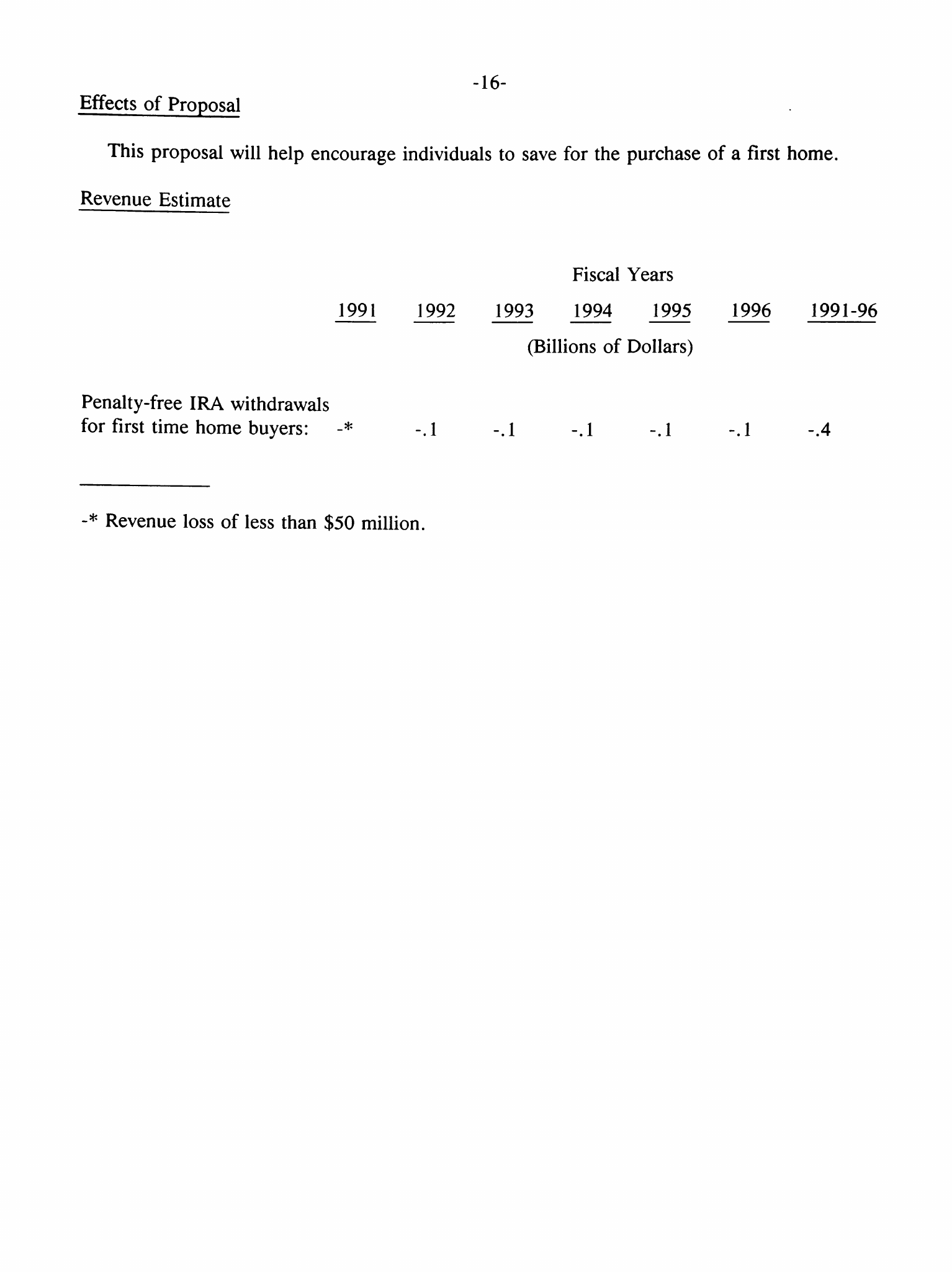

Effects of Proposal

This proposal will help encourage individuals to save for the purchase of a

first

home.

Revenue Estimate

Fiscal Years

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1991-96

(Billions of Dollars)

Penalty-free IRA withdrawals

for

first

time home buyers: -* -.1 -.1 -.1 -.1 -.1 -.4

-* Revenue loss of less than $50 million.

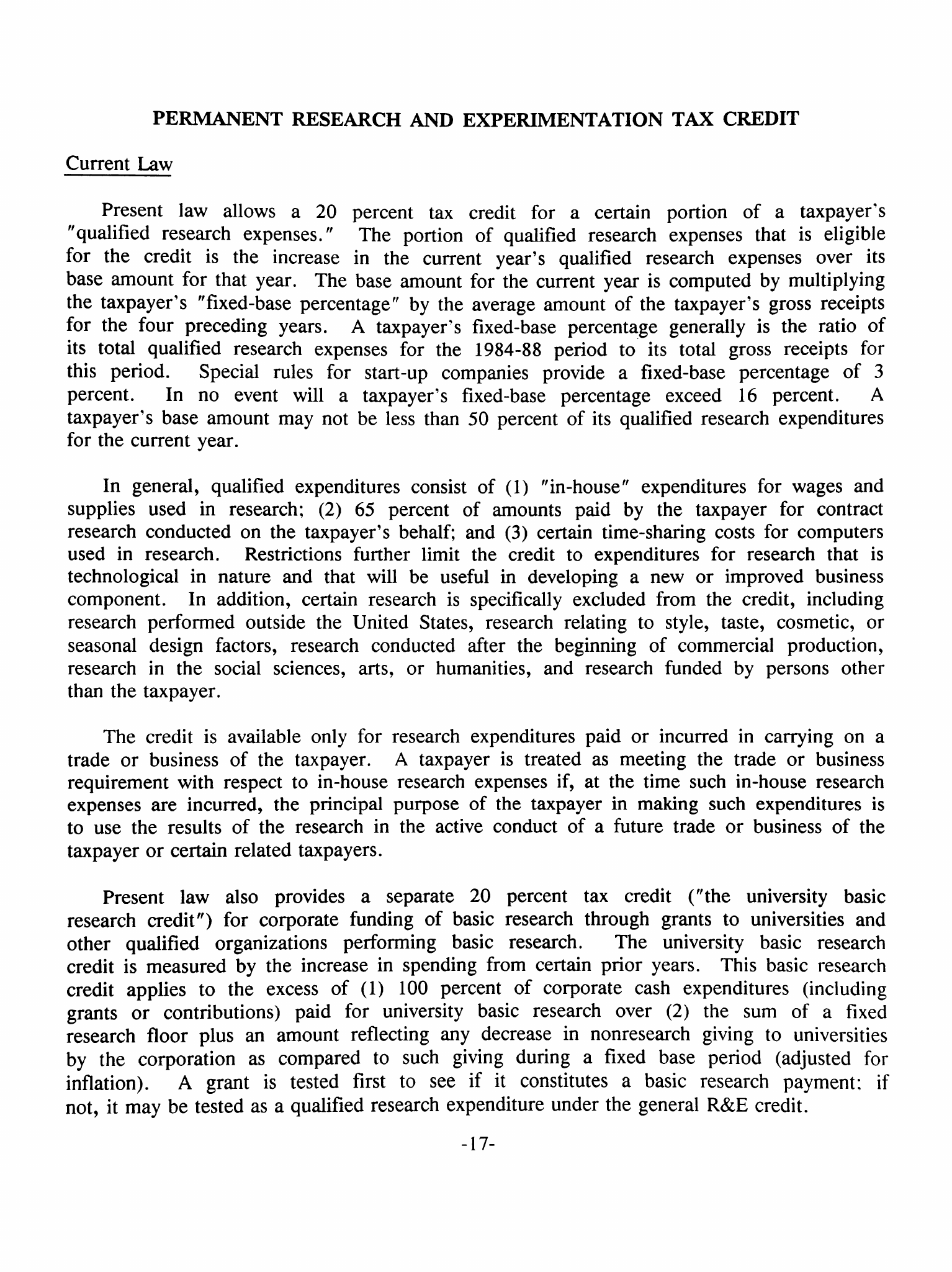

PERMANENT RESEARCH AND EXPERIMENTATION TAX CREDIT

Current Law

Present law allows a 20 percent tax credit for a certain portion of a taxpayer's

"qualified research expenses."

The

portion

of

qualified research expenses that

is

eligible

for

the

credit

is the

increase

in the

current year's qualified research expenses over

its

base amount for that year. The base amount for the current year is computed

by

multiplying

the taxpayer's "fixed-base percentage"

by

the average amount of the taxpayer's gross receipts

for the four preceding years.

A

taxpayer's fixed-base percentage generally

is

the ratio

of

its total qualified research expenses for the 1984-88 period

to

its total gross receipts

for

this period. Special rules

for

start-up companies provide

a

fixed-base percentage

of 3

percent.

In no

event will

a

taxpayer's fixed-base percentage exceed

16

percent.

A

taxpayer's base amount may not be less than 50 percent of its qualified research expenditures

for the current year.

In general, qualified expenditures consist of (1) "in-house" expenditures for wages and

supplies used

in

research; (2)

65

percent

of

amounts paid

by the

taxpayer

for

contract

research conducted

on

the taxpayer's behalf; and (3) certain time-sharing costs for computers

used

in

research. Restrictions further limit the credit

to

expenditures for research that

is

technological

in

nature

and

that will

be

useful

in

developing

a new or

improved business

component.

In

addition, certain research is specifically excluded from the credit, including

research performed outside the United States, research relating

to

style, taste, cosmetic,

or

seasonal design factors, research conducted after the beginning

of

commercial production,

research

in

the social sciences,

arts,

or

humanities,

and

research funded

by

persons other

than the taxpayer.

The credit is available only for research expenditures paid or incurred in carrying on a

trade

or

business

of

the taxpayer.

A

taxpayer is treated

as

meeting the trade

or

business

requirement with respect to in-house research expenses if, at the time such in-house research

expenses are incurred, the principal purpose of the taxpayer in making such expenditures

is

to use the results of the research

in

the active conduct of

a

future trade

or

business

of

the

taxpayer or certain related taxpayers.

Present law also provides a separate 20 percent tax credit ("the university basic

research credit") for corporate funding

of

basic research through grants

to

universities

and

other qualified organizations performing basic research.

The

university basic research

credit is measured

by

the increase in spending from certain prior years. This basic research

credit applies

to the

excess

of

(1)

100

percent

of

corporate cash expenditures (including

grants

or

contributions) paid

for

university basic research over (2)

the sum of a

fixed

research floor plus

an

amount reflecting

any

decrease

in

nonresearch giving

to

universities

by

the

corporation

as

compared

to

such giving during

a

fixed base period (adjusted

for

inflation).

A

grant

is

tested first

to see if it

constitutes

a

basic research payment:

if

not,

it may be tested as

a

qualified research expenditure under the general R&E credit.

-17-

-18-

The R&E credit is aggregated with certain other business credits and made subject to a

limitation based on tax liability. The sum of these credits may reduce the first $25,000 of

regular tax liability without limitation, but may offset only 75 percent of any additional

tax liability. Taxpayers may carry credits not usable in the current year back three years

and forward 15 years.

The amount of any deduction for research expenses is reduced by the amount of the tax

credit taken for that year.

The R&E credit in the form described above is in effect for taxable years beginning after

December 31, 1989. However, the credit will not apply to amounts paid or incurred after

December 31, 1991.

Reasons for Change

The current law tax credit for research provides an incentive for technological

innovation. Although the benefit to the country from such innovation is unquestioned, the

market rewards to those who take the risk of research and experimentation may not be

sufficient to support the level of research activity that is socially desirable. The credit

is intended to reward those engaged in research and experimentation of unproven technologies.

The credit cannot induce additional R&E expenditures unless its future availability is

known at the time firms are planning R&E projects and projecting costs. R&E activity, by its

nature, is long-term, and taxpayers should be able to plan their research activity knowing

that the credit will be available when the research is actually undertaken. Thus, if the R&E

credit is to have the intended incentive effect, it should be made permanent.

Description of Proposal

The R&E credit would be made permanent.

Effects of Proposal

Stable tax laws that encourage research allow taxpayers to undertake research with

greater assurance of the future tax consequences. A permanent R&E credit (including the

university basic research credit) permits taxpayers to establish and expand research

activities without fear that the tax incentive would not be available when the research is

carried out.

Revenue Estimate

Fiscal Years

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1991-96

(Billions of Dollars)

Permanent R&E tax credit: 0 -0.5 -1.0 -1.3 -1.6 -1.8 -6.2

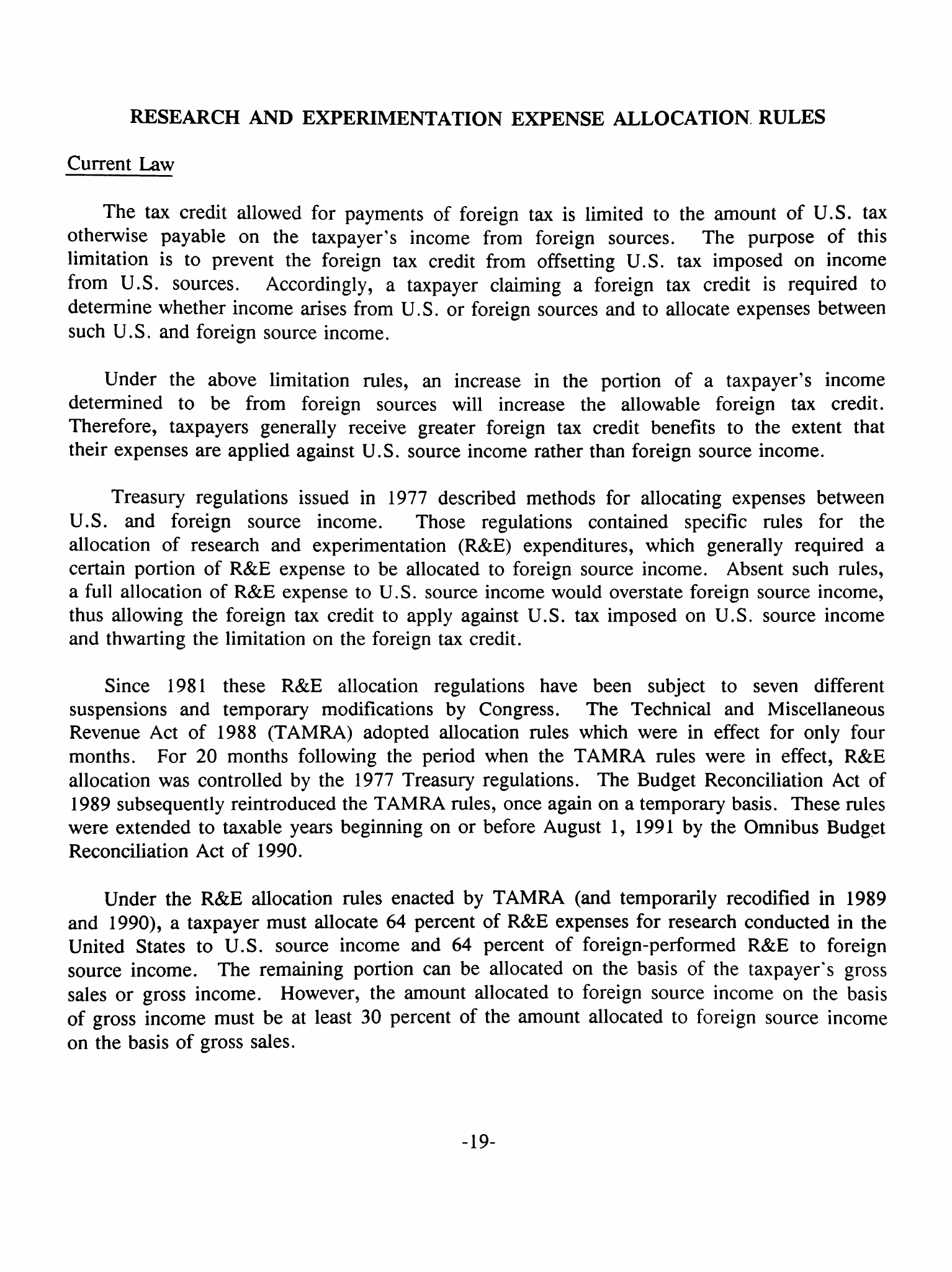

RESEARCH AND EXPERIMENTATION EXPENSE ALLOCATION RULES

Current Law

The tax credit allowed for payments of foreign tax is limited to the amount of U.S. tax

otherwise payable

on the

taxpayer's income from foreign sources.

The

purpose

of

this

limitation

is to

prevent the foreign

tax

credit from offsetting U.S. tax imposed

on

income

from U.S. sources. Accordingly,

a

taxpayer claiming

a

foreign

tax

credit

is

required

to

determine whether income arises from U.S. or foreign sources and to allocate expenses between

such U.S. and foreign source income.

Under the above limitation rules, an increase in the portion of a taxpayer's income

determined

to be

from foreign sources will increase

the

allowable foreign

tax

credit.

Therefore, taxpayers generally receive greater foreign

tax

credit benefits

to

the extent that

their expenses are applied against U.S. source income rather than foreign source income.

Treasury regulations issued in 1977 described methods for allocating expenses between

U.S.

and

foreign source income. Those regulations contained specific rules

for the

allocation

of

research

and

experimentation (R&E) expenditures, which generally required

a

certain portion of R&E expense to

be

allocated to foreign source income. Absent such

rules,

a full allocation of R&E expense to U.S. source income would overstate foreign source income,

thus allowing the foreign tax credit to apply against U.S. tax imposed

on

U.S. source income

and thwarting the limitation on the foreign tax credit.

Since 1981 these R&E allocation regulations have been subject to seven different

suspensions

and

temporary modifications

by

Congress.

The

Technical

and

Miscellaneous

Revenue Act

of

1988 (TAMRA) adopted allocation rules which were

in

effect for only four

months.

For

20

months following the period when the TAMRA rules were

in

effect,

R&E

allocation was controlled

by

the 1977 Treasury regulations. The Budget Reconciliation Act

of

1989 subsequently reintroduced the TAMRA

rules,

once again on a temporary

basis.

These rules

were extended to taxable years beginning on or before August 1, 1991

by

the Omnibus Budget

Reconciliation Act of 1990.

Under the R&E allocation rules enacted by TAMRA (and temporarily recodified in 1989

and

1990),

a

taxpayer must allocate 64 percent of R&E expenses for research conducted in the

United States

to

U.S. source income

and 64

percent

of

foreign-performed

R&E to

foreign

source income. The remaining portion can

be

allocated

on

the basis of the taxpayer's gross

sales

or

gross income. However, the amount allocated to foreign source income

on

the basis

of gross income must

be

at least

30

percent of the amount allocated to foreign source income

on the basis of gross

sales.

-19-

-20-

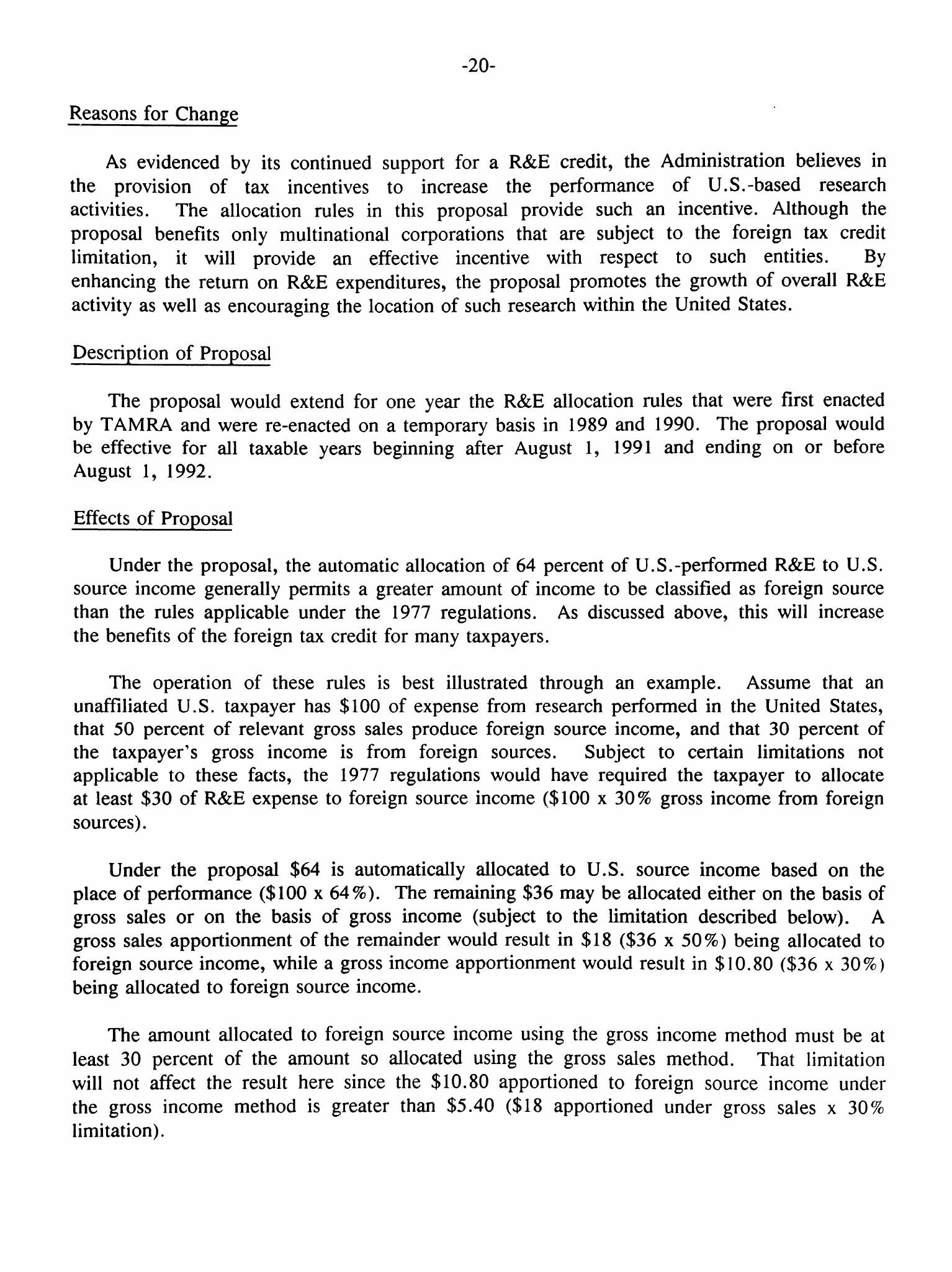

Reasons for Change

As evidenced by its continued support for a R&E credit, the Administration believes in

the provision of tax incentives to increase the performance of U.S.-based research

activities. The allocation rules in this proposal provide such an incentive. Although the

proposal benefits only multinational corporations that are subject to the foreign tax credit

limitation, it will provide an effective incentive with respect to such entities. By

enhancing the return on R&E expenditures, the proposal promotes the growth of overall R&E

activity as well as encouraging the location of such research within the United States.

Description of Proposal

The proposal would extend for one year the R&E allocation rules that were first enacted

by TAMRA and were re-enacted on a temporary basis in 1989 and 1990. The proposal would

be effective for all taxable years beginning after August 1, 1991 and ending on or before

August 1, 1992.

Effects of Proposal

Under the proposal, the automatic allocation of 64 percent of U.S.-performed R&E to U.S.

source income generally permits a greater amount of income to be classified as foreign source

than the rules applicable under the 1977 regulations. As discussed above, this will increase

the benefits of the foreign tax credit for many taxpayers.

The operation of these rules is best illustrated through an example. Assume that an

unaffiliated U.S. taxpayer has $100 of expense from research performed in the United States,

that 50 percent of relevant gross sales produce foreign source income, and that 30 percent of

the taxpayer's gross income is from foreign sources. Subject to certain limitations not

applicable to these facts, the 1977 regulations would have required the taxpayer to allocate

at least $30 of R&E expense to foreign source income ($100 x 30% gross income from foreign

sources).

Under the proposal $64 is automatically allocated to U.S. source income based on the

place of performance ($100 x

64%).

The remaining $36 may be allocated either on the basis of

gross sales or on the basis of gross income (subject to the limitation described

below).

A

gross sales apportionment of the remainder would result in $18 ($36 x 50%) being allocated to

foreign source income, while a gross income apportionment would result in $10.80 ($36 x 30%)

being allocated to foreign source income.

The amount allocated to foreign source income using the gross income method must be at

least 30 percent of the amount so allocated using the gross sales method. That limitation

will not affect the result here since the $10.80 apportioned to foreign source income under

the gross income method is greater than $5.40 ($18 apportioned under gross sales x 30%

limitation).

-21-

As a result of the allocation rules in the proposal, the taxpayer in this example must

allocate at least $10.80 of U.S.-performed R&E expense to foreign source income, compared to

the $30 required to be so allocated under the 1977 regulations.

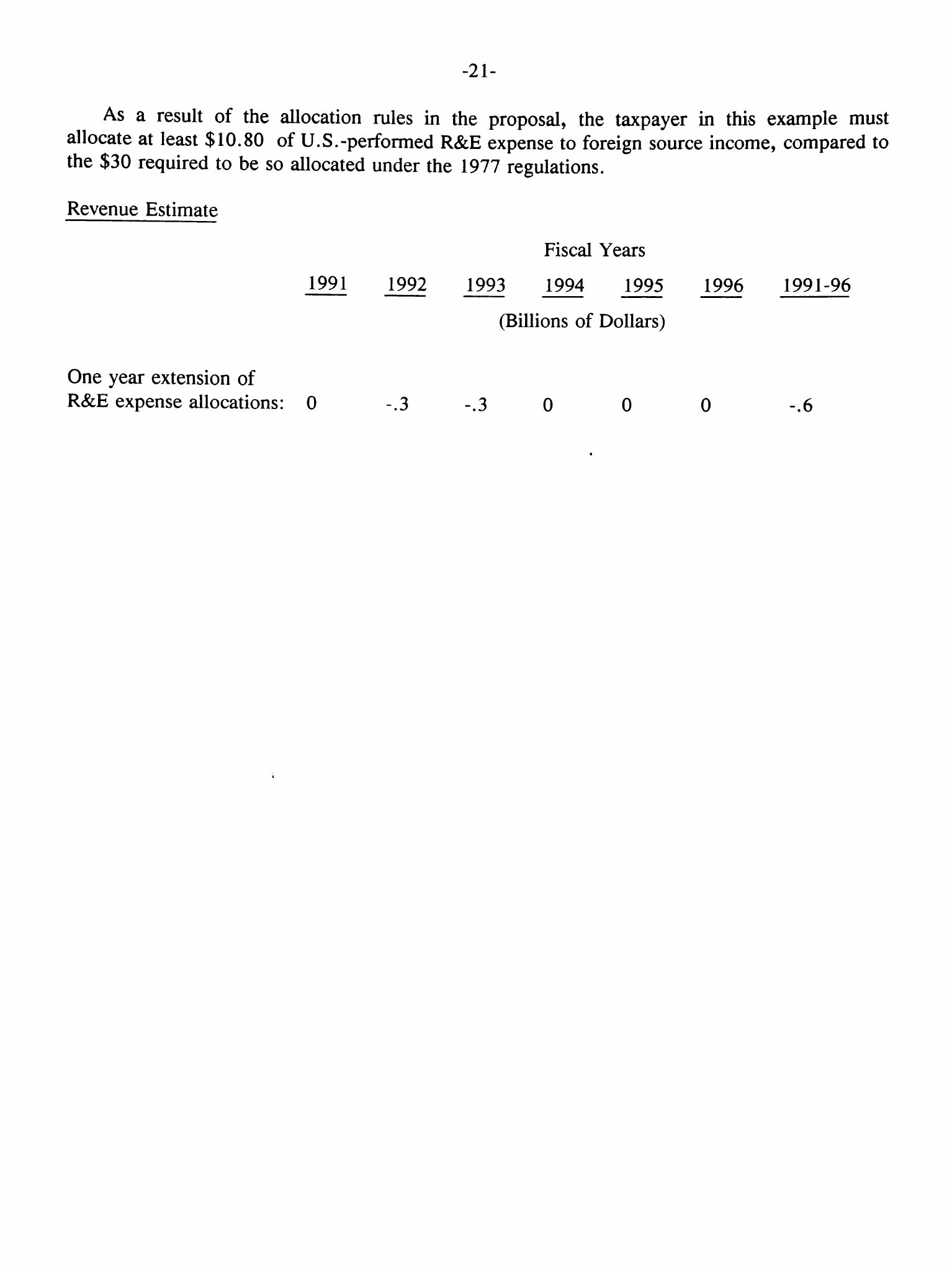

Revenue Estimate

Fiscal Years

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1991-96

(Billions of Dollars)

One year extension of

R&E expense allocations: 0 -.3 -.3 0 0 0 -.6

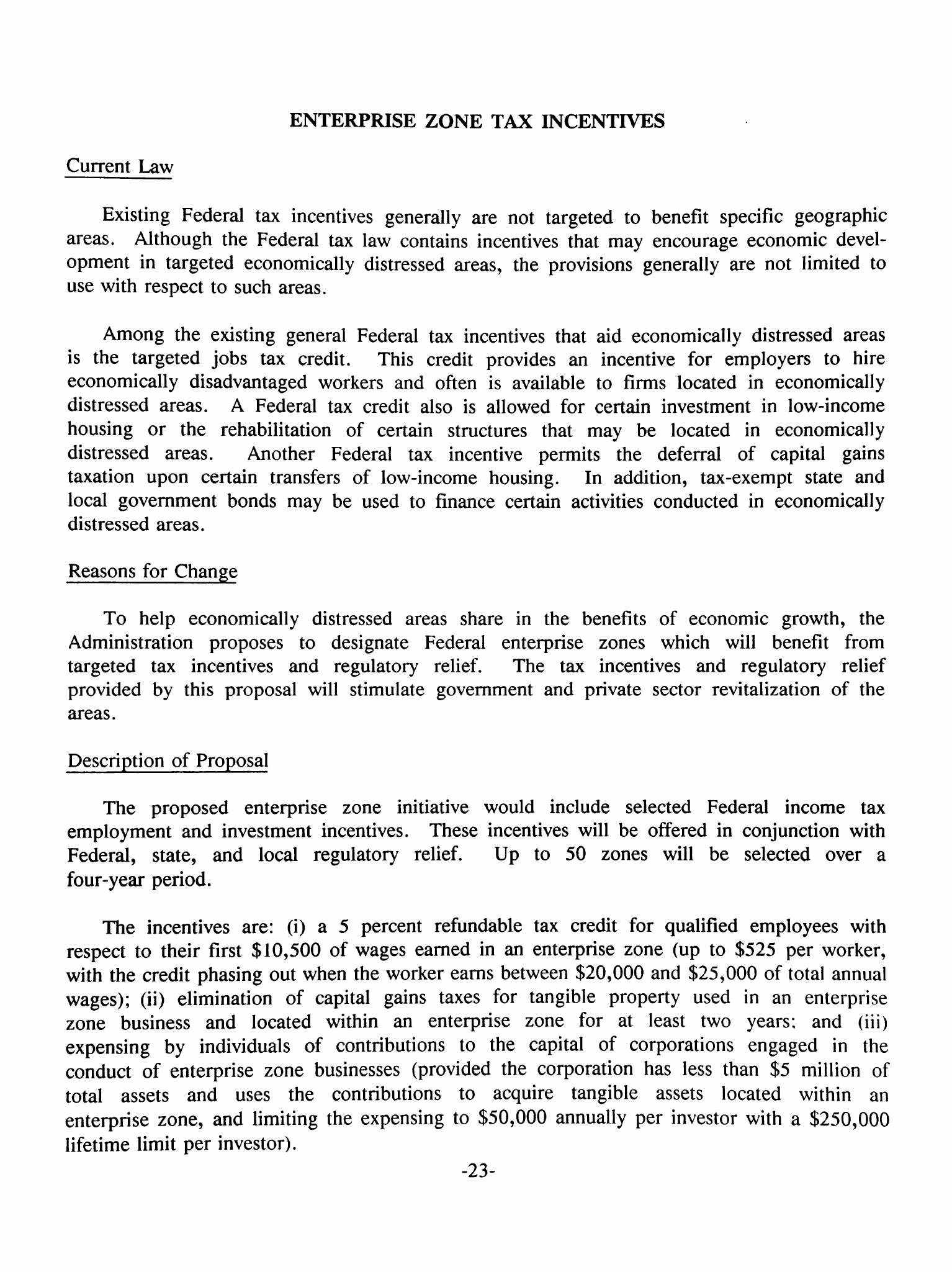

ENTERPRISE ZONE TAX INCENTIVES

Current Law

Existing Federal tax incentives generally are not targeted to benefit specific geographic

areas.

Although the Federal tax law contains incentives that may encourage economic devel-

opment in targeted economically distressed areas, the provisions generally are not limited to

use with respect to such areas.

Among the existing general Federal tax incentives that aid economically distressed areas

is the targeted jobs tax credit. This credit provides an incentive for employers to hire

economically disadvantaged workers and often is available to firms located in economically

distressed areas. A Federal tax credit also is allowed for certain investment in low-income

housing or the rehabilitation of certain structures that may be located in economically

distressed areas. Another Federal tax incentive permits the deferral of capital gains

taxation upon certain transfers of low-income housing. In addition, tax-exempt state and

local government bonds may be used to finance certain activities conducted in economically

distressed areas.

Reasons for Change

To help economically distressed areas share in the benefits of economic growth, the

Administration proposes to designate Federal enterprise zones which will benefit from

targeted tax incentives and regulatory relief. The tax incentives and regulatory relief

provided by this proposal will stimulate government and private sector revitalization of the

areas.

Description of Proposal

The proposed enterprise zone initiative would include selected Federal income tax

employment and investment incentives. These incentives will be offered in conjunction with

Federal, state, and local regulatory relief. Up to 50 zones will be selected over a

four-year period.

The incentives are: (i) a 5 percent refundable tax credit for qualified employees with

respect to their

first

$10,500 of wages earned in an enterprise zone (up to $525 per worker,

with the credit phasing out when the worker earns between $20,000 and $25,000 of total annual

wages);

(ii) elimination of capital gains taxes for tangible property used in an enterprise

zone business and located within an enterprise zone for at least two years; and (iii)

expensing by individuals of contributions to the capital of corporations engaged in the

conduct of enterprise zone businesses (provided the corporation has less than $5 million of

total assets and uses the contributions to acquire tangible assets located within an

enterprise zone, and limiting the expensing to $50,000 annually per investor with a $250,000

lifetime limit per

investor).

-23-

-24-

The willingness of states and localities to "match" Federal incentives will be considered

in selecting the special enterprise zones to receive these additional Federal incentives.

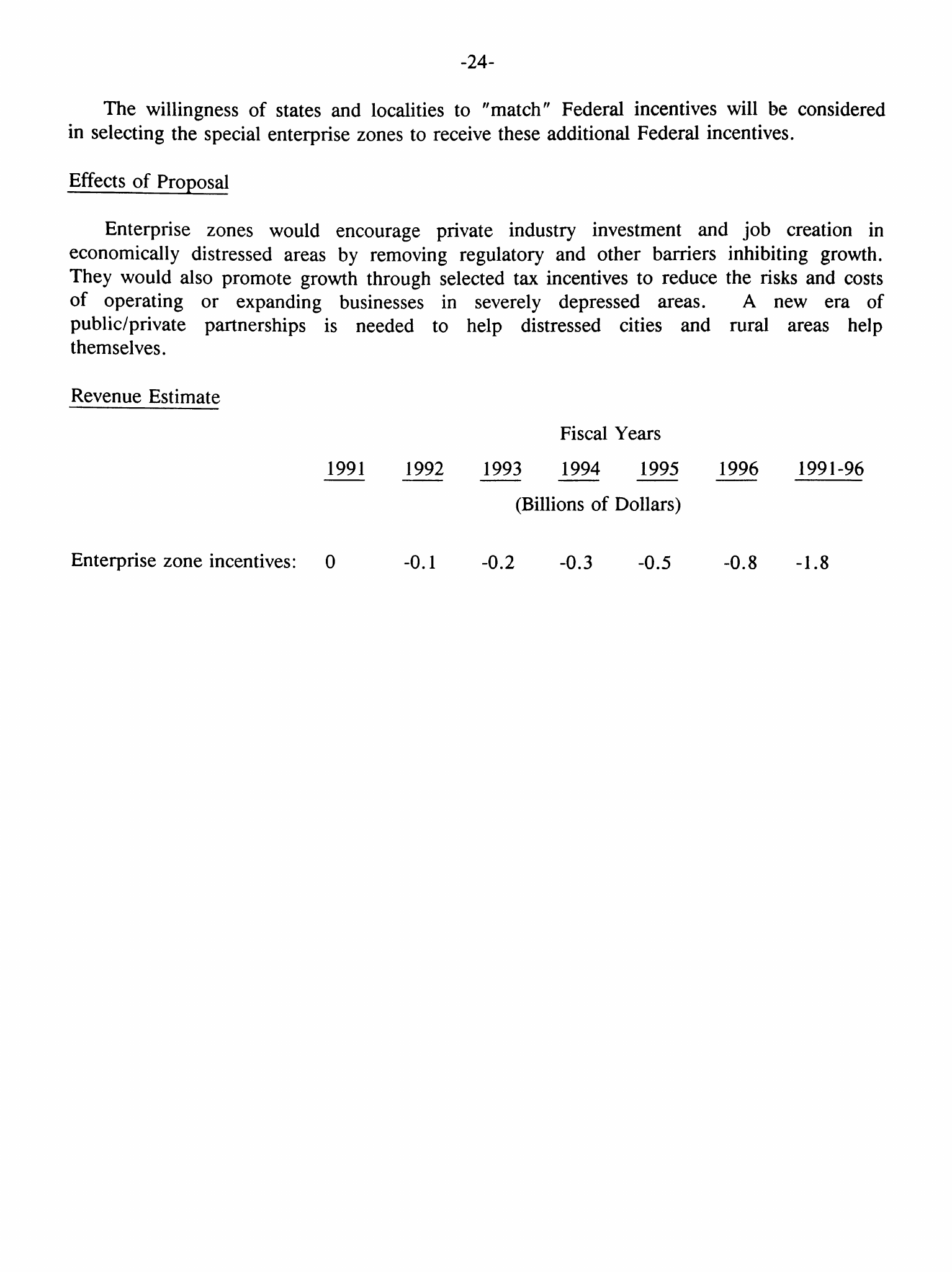

Effects of Proposal

Enterprise zones would encourage private industry investment and job creation in

economically distressed areas by removing regulatory and other barriers inhibiting growth.

They would also promote growth through selected tax incentives to reduce the risks and costs

of operating or expanding businesses in severely depressed areas. A new era of

public/private partnerships is needed to help distressed cities and rural areas help

themselves.

Revenue Estimate

Fiscal Years

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1991-96

(Billions of Dollars)

Enterprise zone incentives: 0 -0.1 -0.2 -0.3 -0.5 -0.8 -1.8

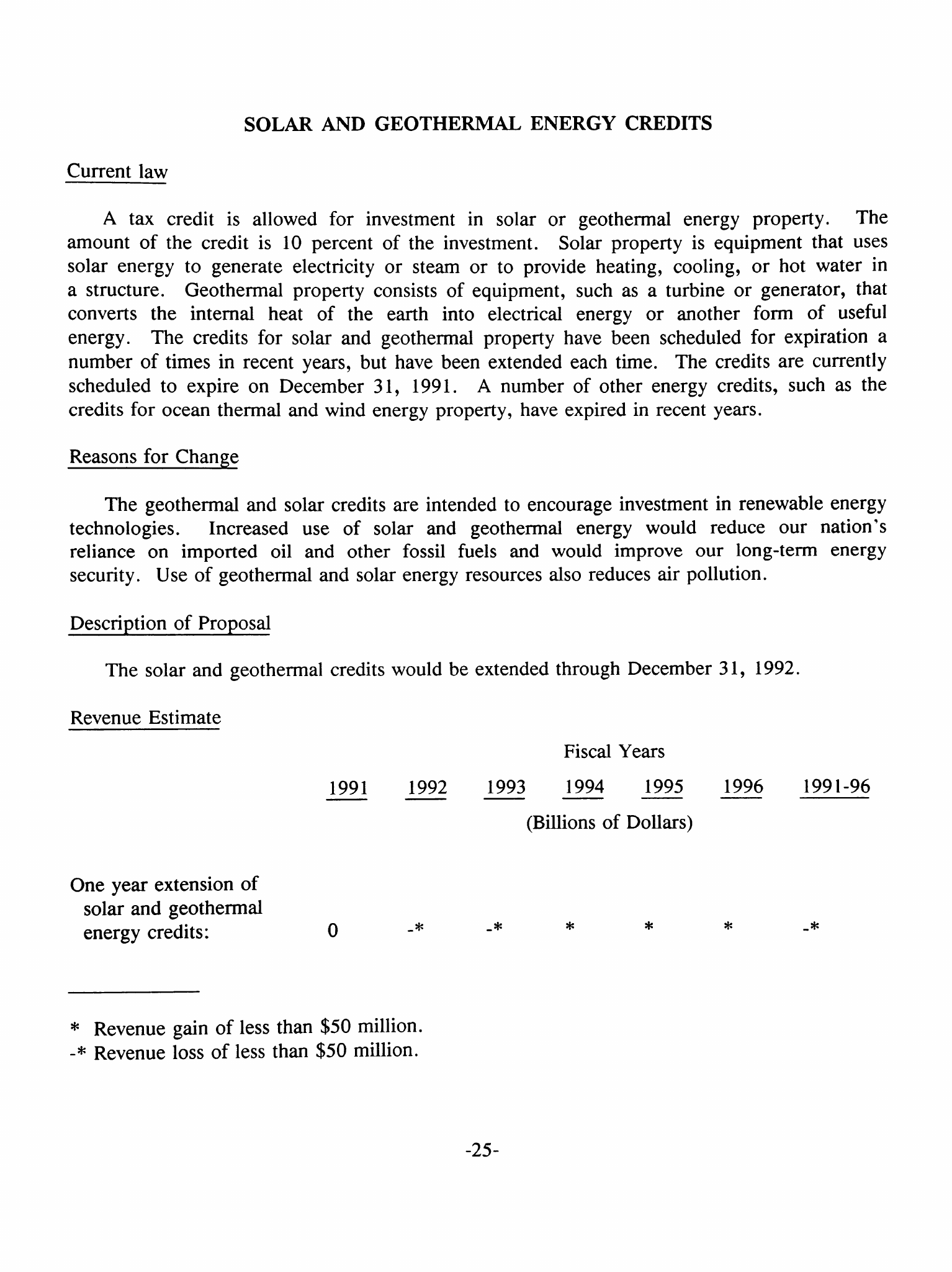

SOLAR AND GEOTHERMAL ENERGY CREDITS

Current law

A tax credit is allowed for investment in solar or geothermal energy property. The

amount of the credit is

10

percent of the investment. Solar property is equipment that uses

solar energy

to

generate electricity

or

steam

or to

provide heating, cooling,

or

hot water

in

a structure. Geothermal property consists of equipment, such as

a

turbine

or

generator, that

converts

the

internal heat

of the

earth into electrical energy

or

another form

of

useful

energy. The credits for solar and geothermal property have been scheduled for expiration

a

number of times in recent years, but have been extended each time. The credits are currently

scheduled

to

expire

on

December 31, 1991.

A

number of other energy credits, such

as the

credits for ocean thermal and wind energy property, have expired in recent years.

Reasons for Change

The geothermal and solar credits are intended to encourage investment in renewable energy

technologies. Increased

use of

solar

and

geothermal energy would reduce

our

nation's

reliance

on

imported

oil and

other fossil fuels

and

would improve

our

long-term energy

security. Use of geothermal and solar energy resources also reduces air pollution.

Description of Proposal

The solar and geothermal credits would be extended through December 31, 1992.

Revenue Estimate

Fiscal Years

1991

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996

1991-96

(Billions of Dollars)

One year extension of

solar and geothermal

energy

credits:

0 _*_**** _*

*

Revenue gain of less than $50 million.

-*

Revenue loss of less than $50 million.

-25-

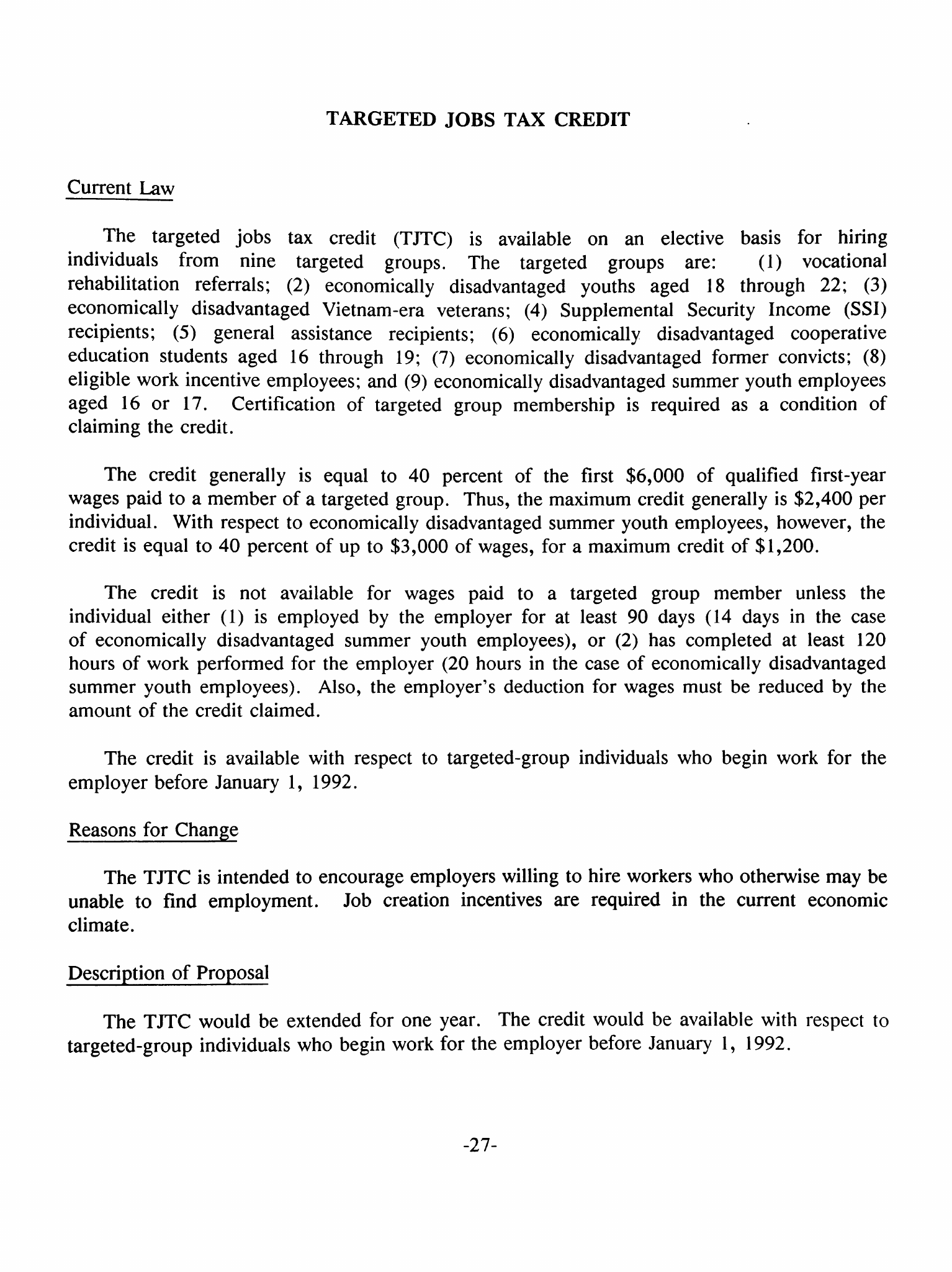

TARGETED JOBS TAX CREDIT

Current Law

The targeted jobs tax credit (TJTC) is available on an elective basis for hiring

individuals from nine targeted groups.

The

targeted groups

are: (1)

vocational

rehabilitation referrals;

(2)

economically disadvantaged youths aged

18

through 22;

(3)

economically disadvantaged Vietnam-era veterans; (4) Supplemental Security Income

(SSI)

recipients;

(5)

general assistance recipients;

(6)

economically disadvantaged cooperative

education students aged

16

through 19; (7) economically disadvantaged former convicts;

(8)

eligible work incentive employees; and

(9)

economically disadvantaged summer youth employees

aged

16 or

17. Certification

of

targeted group membership

is

required

as a

condition

of

claiming the credit.

The credit generally is equal to 40 percent of the first $6,000 of qualified first-year

wages paid to

a

member of a targeted group.

Thus,

the maximum credit generally is $2,400 per

individual.

With respect to economically disadvantaged summer youth employees, however, the

credit is equal to 40 percent of up to $3,000 of

wages,

for

a

maximum credit of

$1,200.

The credit is not available for wages paid to a targeted group member unless the

individual either (1) is employed

by

the employer for at least

90

days (14 days

in

the case

of economically disadvantaged summer youth

employees),

or

(2) has completed

at

least

120

hours of work performed for the employer (20 hours in the case of economically disadvantaged

summer youth

employees).

Also, the employer's deduction for wages must be reduced

by

the

amount of the credit claimed.

The credit is available with respect to targeted-group individuals who begin work for the

employer before January 1, 1992.

Reasons for Change

The TJTC is intended to encourage employers willing to hire workers who otherwise may be

unable

to

find employment.

Job

creation incentives

are

required

in the

current economic

climate.

Description of Proposal

The TJTC would be extended for one year. The credit would be available with respect to

targeted-group individuals who begin work for the employer before January 1, 1992.

-27-

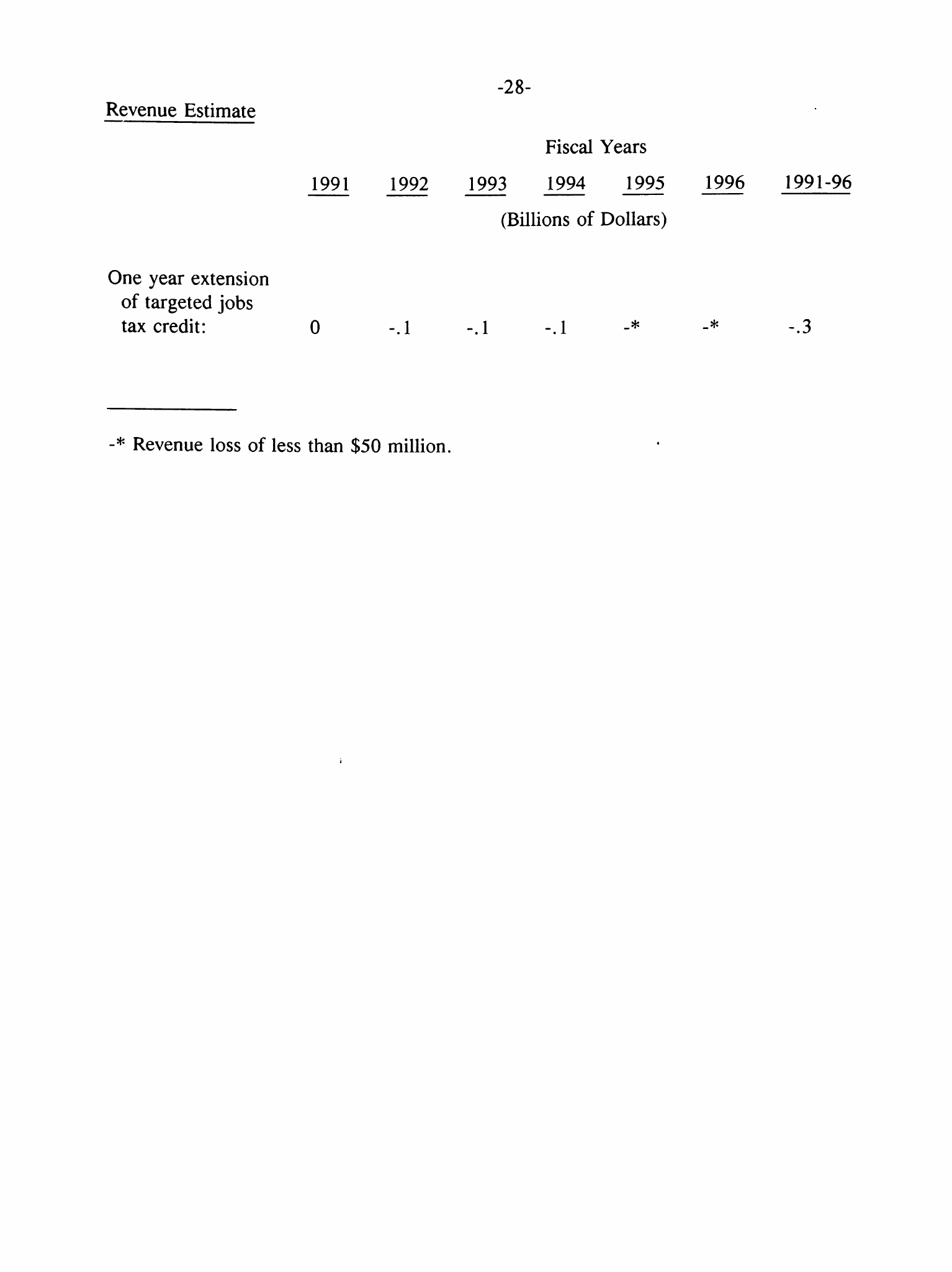

Revenue Estimate

-28-

Fiscal Years

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1991-96

(Billions of Dollars)

One year extension

of targeted jobs

tax credit: 0 -.1 -.1 -.1 -* -* -.3

-* Revenue loss of less than $50 million.

DEDUCTION FOR SPECIAL NEEDS ADOPTIONS

Current Law

Expenses associated with the adoption of children are not deductible under current law.

However, expenses associated with the adoption

of

special needs children are reimbursable

under the Federal-State Adoption Assistance Program (Title IV-E of the Social Security Act).

Special needs children are those who

by

virtue of special conditions such as age, physical

or

mental handicap,

or

combination

of

circumstances, are difficult

to

place for adoption.

The

Adoption Assistance Program includes several components. One of these components requires

States

to

reimburse families for costs associated with the process

of

adopting special needs

children. The Federal Government shares

50

percent of these costs

up

to

a

maximum Federal

share

of

$1,000 per child. Reimbursable expenses include those associated directly with

the

adoption process such

as

legal costs, social service review,

and

transportation costs. Some

children

are

also eligible

for

continuing Federal-State assistance under Title IV-E

of the

Social Security Act. This assistance includes Medicaid. Other children

may be

eligible for

continuing assistance under State-only programs.

Reasons for Change

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 (the 1986 Act) repealed the deduction for adoption expenses

associated with special needs children. Under prior law,

a

deduction

of up to

$1,500

of

expenses associated with the adoption of special needs children was allowed.

The

1986

Act

provided for

a

new outlay program under the existing Adoption Assistance Program to reimburse

expenses associated with

the

adoption process

of

these children.

The

group

of

children

covered under the outlay program is somewhat broader than the group covered

by

the prior

deduction.

The

prior

law

deduction

was

available only for special needs children assisted

under Federal welfare programs, Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Title IV-E Foster

Care,

or

Supplemental Security Income.

The

current adoption assistance outlay program

provides assistance

for

adoption expenses

for

these special needs children,

as

well

as

special needs children in private and State-only programs.

Repeal of the special needs adoption deduction may have appeared to some as a lessening

of the Federal concern for the adoption of special needs children.

An important purpose of the Adoption Assistance Program is to enable families in modest

circumstances

to

adopt special needs children.

In a

number

of

cases

the

children

are in

foster care with

the

prospective adoptive parents.

The

prospective parents would like

to

formally adopt the child but find that

to do so

would impose

a

financial hardship

on the

entire family.

While the majority of eligible expenses are expected to be reimbursed under the

continuing expenditure program,

the

Administration

is

concerned that

in

some cases

the

limits

may be set

below actual cost

in

high-cost areas

or in

special circumstances.

Moreover, inclusion

in the tax

code

of a

deduction

for

special needs children

may

alert

families who are hoping to adopt

a

child to the many forms of assistance provided to families

adopting

a

child with special needs.

-29-

-30-

Description of Proposal

The proposal would permit the deduction from income of expenses incurred that are

associated with the adoption of special needs children, up to a maximum of $3,000 per child.

Eligible expenses would be limited to those directly associated with the adoption process

that are eligible for reimbursement under the Adoption Assistance Program. These include

court costs, legal expenses, social service review, and transportation costs. Only expenses

for adopting children defined as eligible under the rules of the Adoption Assistance Program

would be allowed. Expenses which were deducted but reimbursed would be included in income in

the year in which the reimbursement occurred. The proposal would be effective January 1,

1992.

Effects of Proposal

The proposal when combined with the current outlay program would assure that reasonable

expenses associated with the process of adopting a special needs child do not cause financial

hardship for the adoptive parents. The proposed deduction would supplement the current

Federal outlay program. In addition, the proposal highlights the Administration's concern

that adoption of these children be specially encouraged and may call to the attention of

families interested in adoption the various programs that help families adopting children

with special needs.

There is currently uncertainty regarding whether Federal and State reimbursements are

income to the adopting families. The proposal would clarify the treatment of reimbursements

by making them includable in income but also deductible, up to $3,000 of eligible expenses

per child. Additionally, qualified expenses up to this limit would be deductible even though

not reimbursed.

While the costs of adoption of a special needs child are only a small part of the total

costs associated with adoption of these children, the Administration believes that it is

important to remove this small one-time cost barrier that might leave any of these children

without a permanent family.

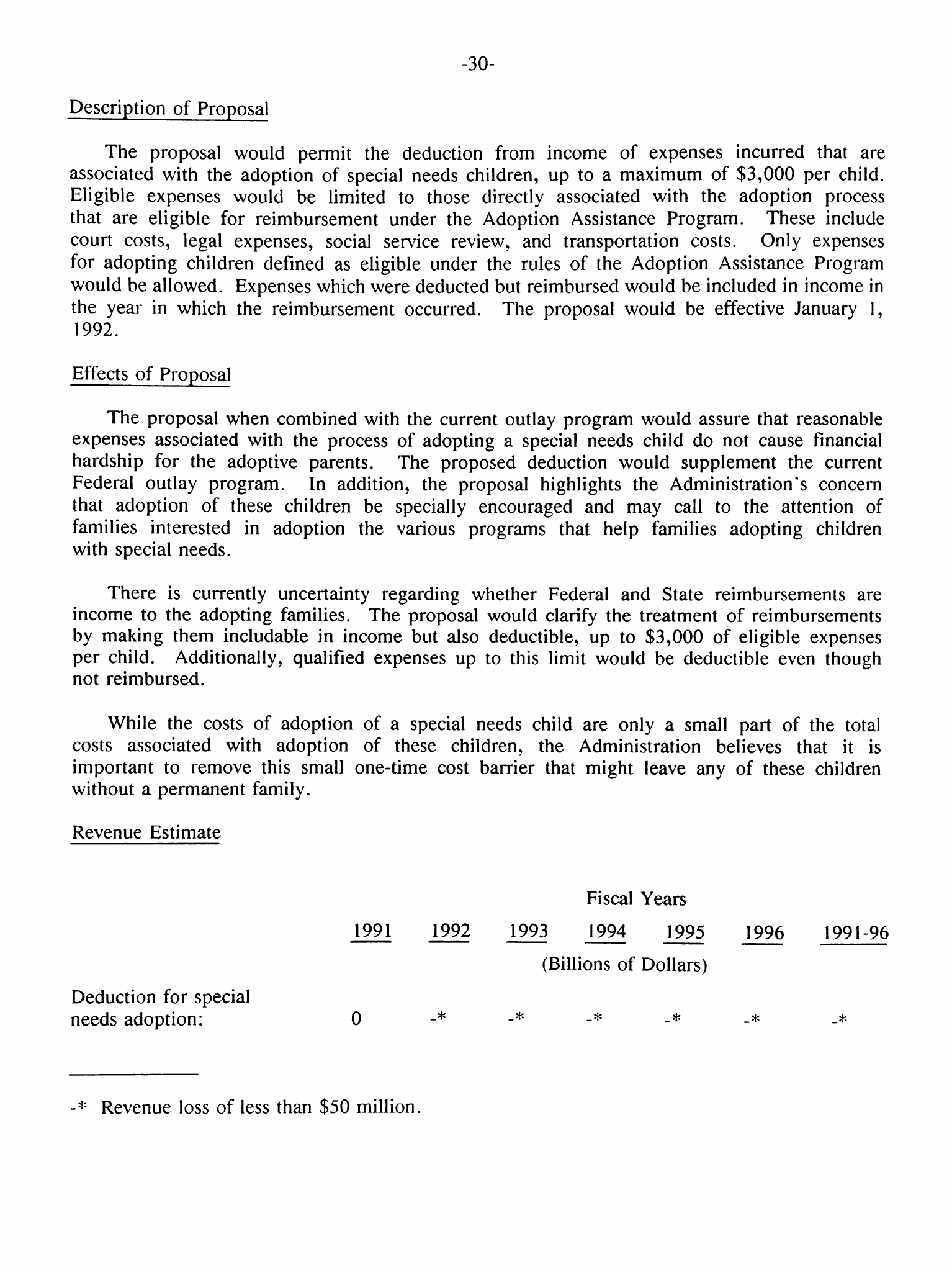

Revenue Estimate

Fiscal Years

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1991-96

(Billions of Dollars)

Deduction for special

needs adoption: 0 -* -* -* -* -* .*

-* Revenue loss of less than $50 million.

LOW-INCOME HOUSING TAX CREDIT

Current Law

A tax credit is allowed for certain expenditures with respect to low-income residential

rental housing.

The

low-income housing credit generally

may be

claimed

by

owners

of

qualified low-income buildings

in

equal annual installments over

a

10-year credit period

as

long

as the

buildings continue

to

provide low-income housing over

a

15-year compliance

period.

In general, the discounted present value of the installments may be as much as 70 percent

of eligible expenditures. Eligible expenditures include

the

depreciable costs

of new

construction

and

substantial rehabilitations. They also include

the

cost

of

acquiring

existing buildings which have been substantially rehabilitated

so

long

as

they have not been

placed

in

service within

the

previous

10

years

and are not

already subject

to a

15-year

compliance period. The basis

of

property

is

not reduced

by

the amount

of

the credit for

purposes of depreciation and capital gain.

The annual credit available for a building cannot exceed the amount allocated to the

building

by

the designated State

or

local housing agency.

As

originally enacted, the total

allocations

by

the housing agency in

a

given year could not exceed the product of $1.25 and

the State's population.

A

State credit allocation

is not

required, however,

for

certain

projects financed with tax-exempt bonds subject

to

the State's private activity bond volume

limitation.

States could not originally allocate the low-income housing credit after 1989. The

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 extended each State's allocation authority through

1990,

but at a

reduced annual level

of

$0.9375 per state resident.

The

Omnibus Budget

Reconciliation Act

of

1990, however, increased the allocation authority for 1990 to $1.25 per

State resident and extended allocation authority through 1991 at the same annual level.

Reasons for Change

The low-income housing credit encourages the private sector to construct and rehabilitate

the nation's rental housing stock and to make it available to the working poor and other low-

income families.

In

addition

to

tenant-based housing vouchers

and

certificates,

the

credit

is an important mechanism for providing Federal assistance to rental households.

Description of Proposal

The proposal would extend the authority of States to allocate the credit through 1992 at

an annual level of $1.25 per State resident.

-31-

-32-

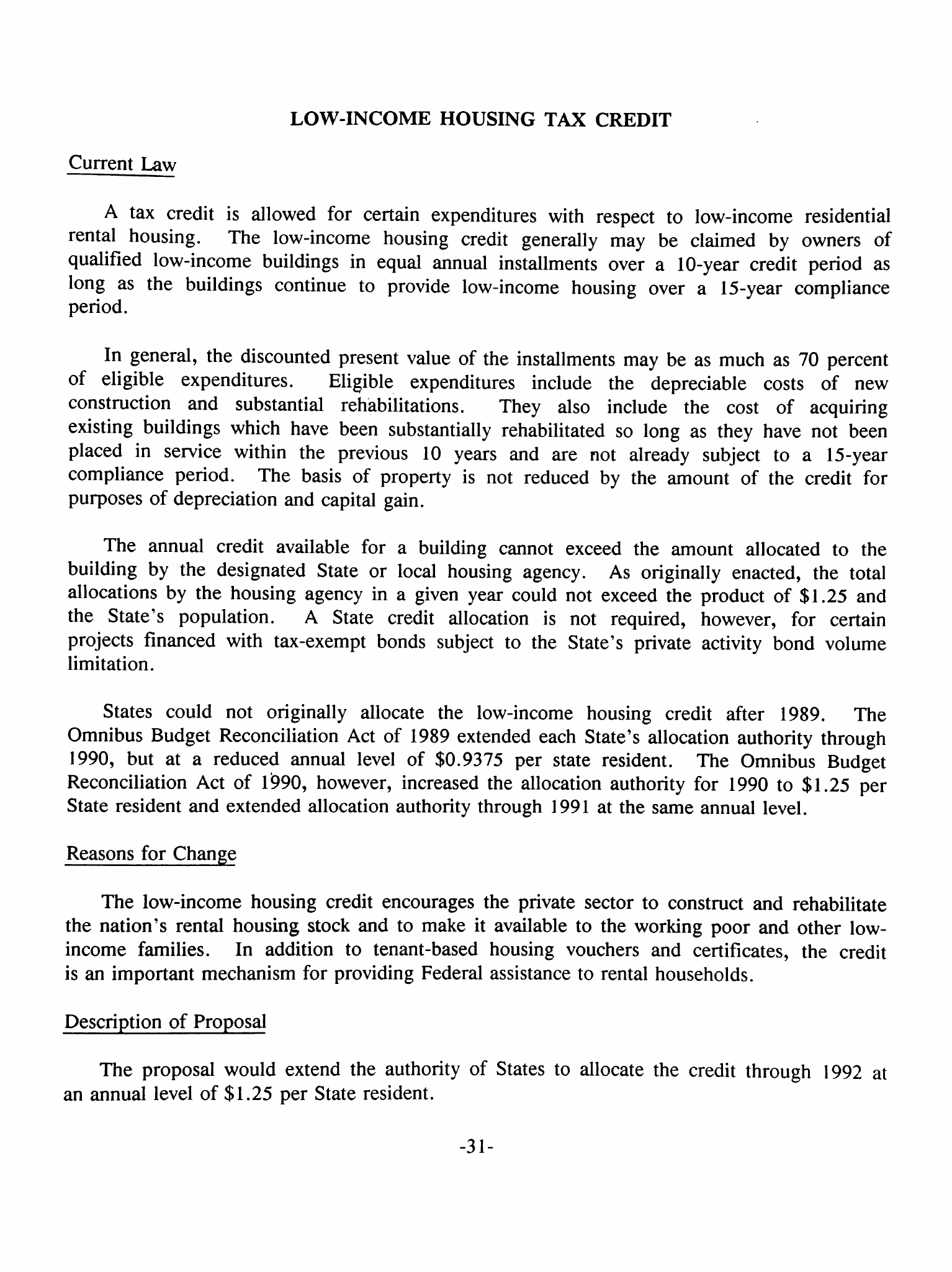

Revenue Estimate

Fiscal Years

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995

(Billions of Dollars)

One year extension of

low-income housing

tax credit:

0 -0.1

-0.2 -0.3 -0.3

HEALTH INSURANCE DEDUCTION FOR THE SELF-EMPLOYED

Current Law

Current law generally allows a self-employed individual to deduct as a business expense

up

to 25

percent of the amount paid during

a

taxable year for health insurance coverage for

himself, his spouse, and his dependents. The deduction is not allowed if the self-employed

individual

or

his

or her

spouse

is

eligible

for

employer-paid health benefits. Originally,

this deduction was only available if the insurance was provided under

a

plan that satisfied

the non-discrimination requirements

of

section

89 of

the Code. Section

89

has since been

repealed retroactively, however,

and no

non-discrimination requirements currently apply

to

such insurance. The value

of

any coverage provided for such individuals

and

their families

by

the

business

is not

deductible

for

self-employment

tax

purposes.

The

deduction

is

scheduled to expire after December

31,

1991.

Reasons for Change

The 25 percent deduction for health insurance costs of self-employed individuals was

added

by

the

Tax

Reform Act

of

1986 because

of a

disparity between the tax treatment

of

owners

of

incorporated

and

unincorporated businesses (e.g., partnerships

and

sole

proprietorships).

Under prior law, incorporated businesses could generally deduct,

as an

employee compensation expense, the full cost of any health insurance coverage provided for

their employees (including owners serving

as

employees)

and

their employees' spouses

and

dependents.

By

contrast, self-employed individuals operating through

an

unincorporated

business could only deduct

the

cost

of

health insurance coverage for themselves

and

their

spouses and dependents to the extent that

it,

together with other allowable medical expenses,

exceeded

5

percent of their adjusted gross income. (Coverage provided

to

employees of the

self-employed, however, was and remains

a

deductible business expense for the self-employed.)

The special

25

percent deduction

was

designed

to

mitigate this disparity

in

treatment.

Further,

the Tax

Reform

Act of

1986 raised

the

floor

for

deductible medical expenses

(including health insurance) to 7.5 percent of adjusted gross income.

Description of Proposal

The proposal would extend the 25 percent deduction through December 31, 1992.

Effects of Proposal

The proposal will continue to reduce the disparity in tax treatment between self-employed

individuals and owners of incorporated businesses, compared to prior law.

-33-

-34-

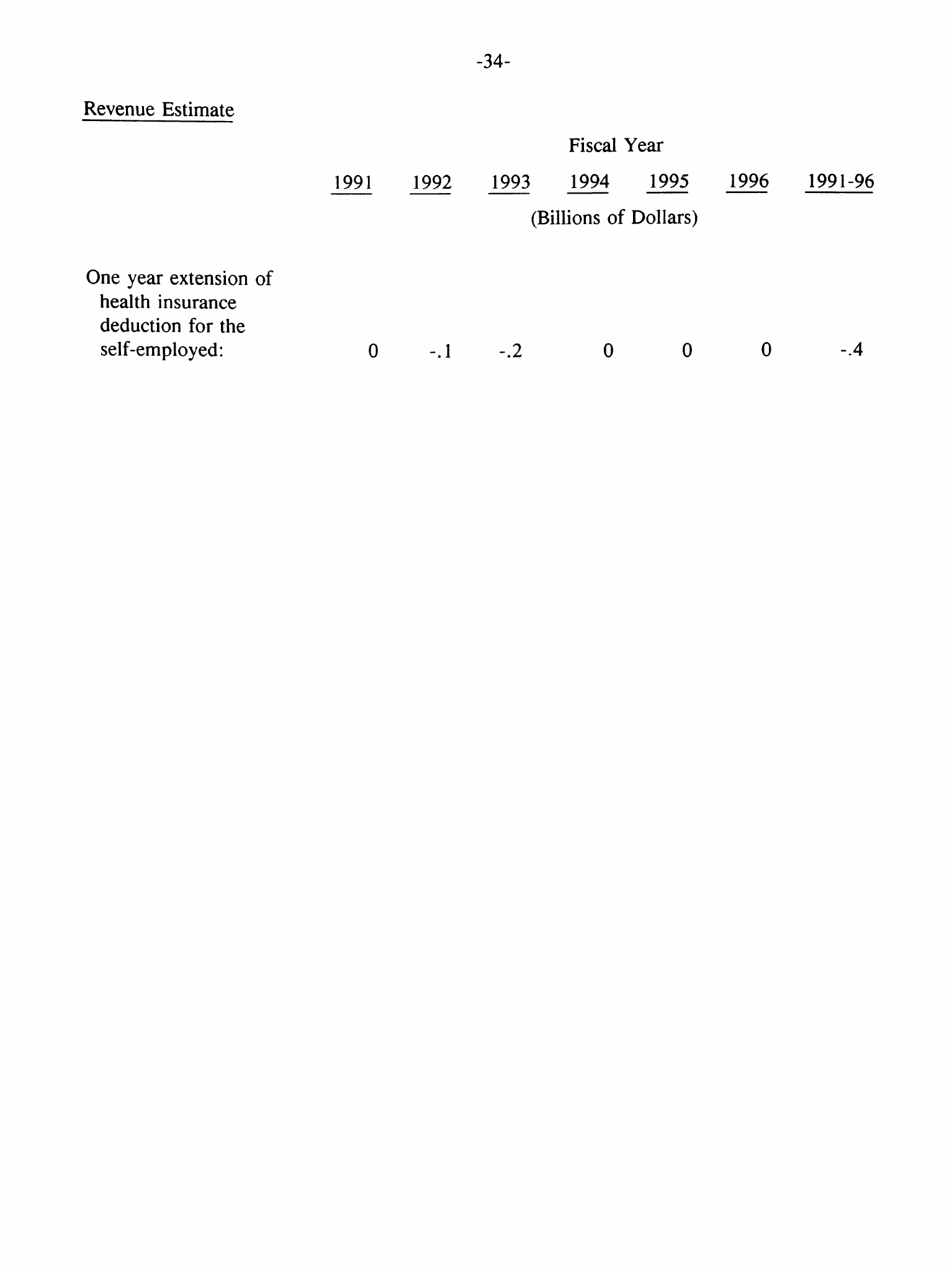

Revenue Estimate

Fiscal Year

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1991-96

(Billions of Dollars)

One year extension of

health insurance

deduction for the

self-employed: 0 -.1 -.2 0 0 0 -.4

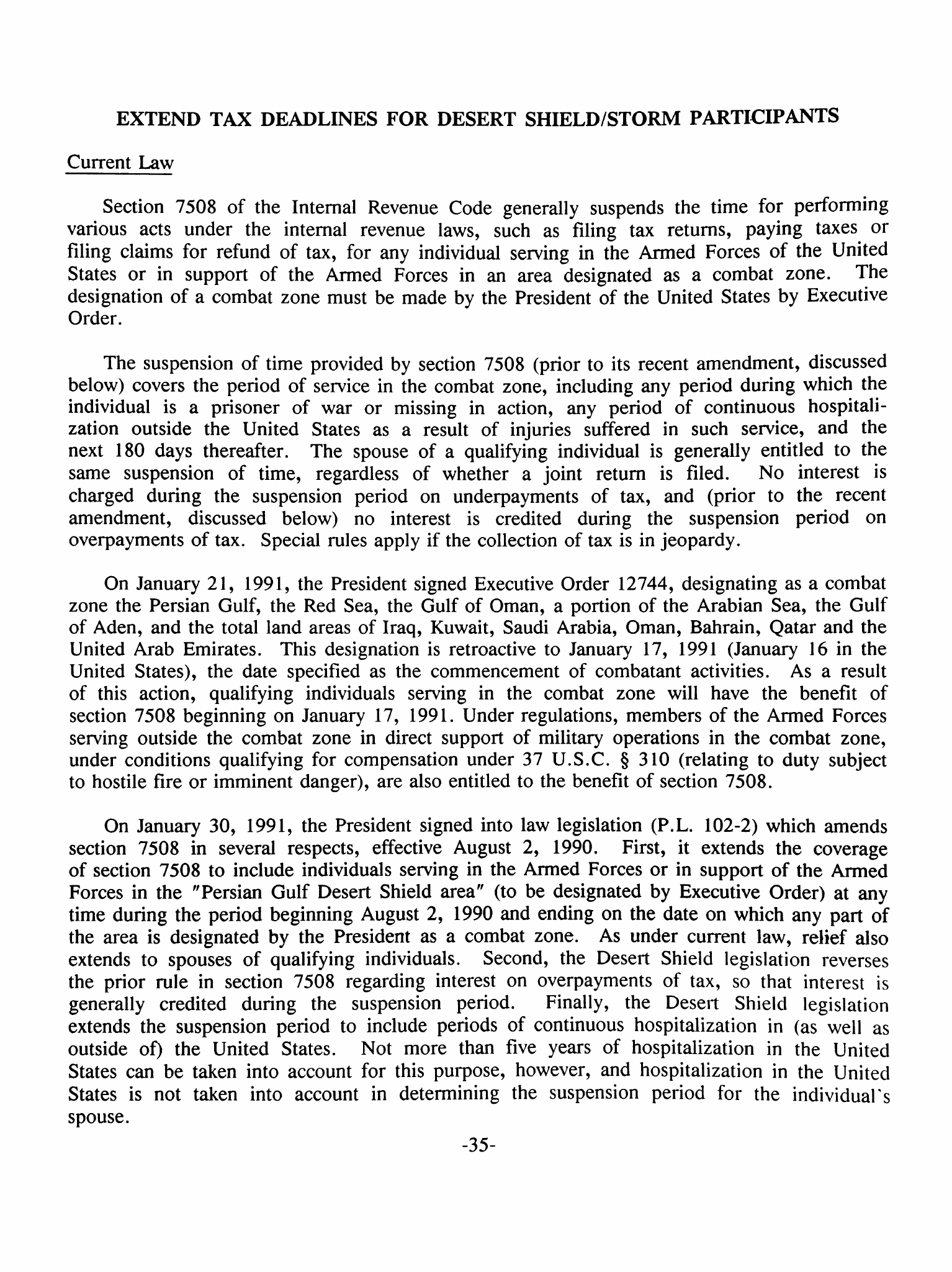

EXTEND TAX DEADLINES FOR DESERT SHIELD/STORM PARTICIPANTS

Current Law

Section 7508 of the Internal Revenue Code generally suspends the time for performing

various acts under

the

internal revenue

laws,

such

as

filing

tax

returns, paying taxes

or

filing claims for refund of tax, for any individual serving

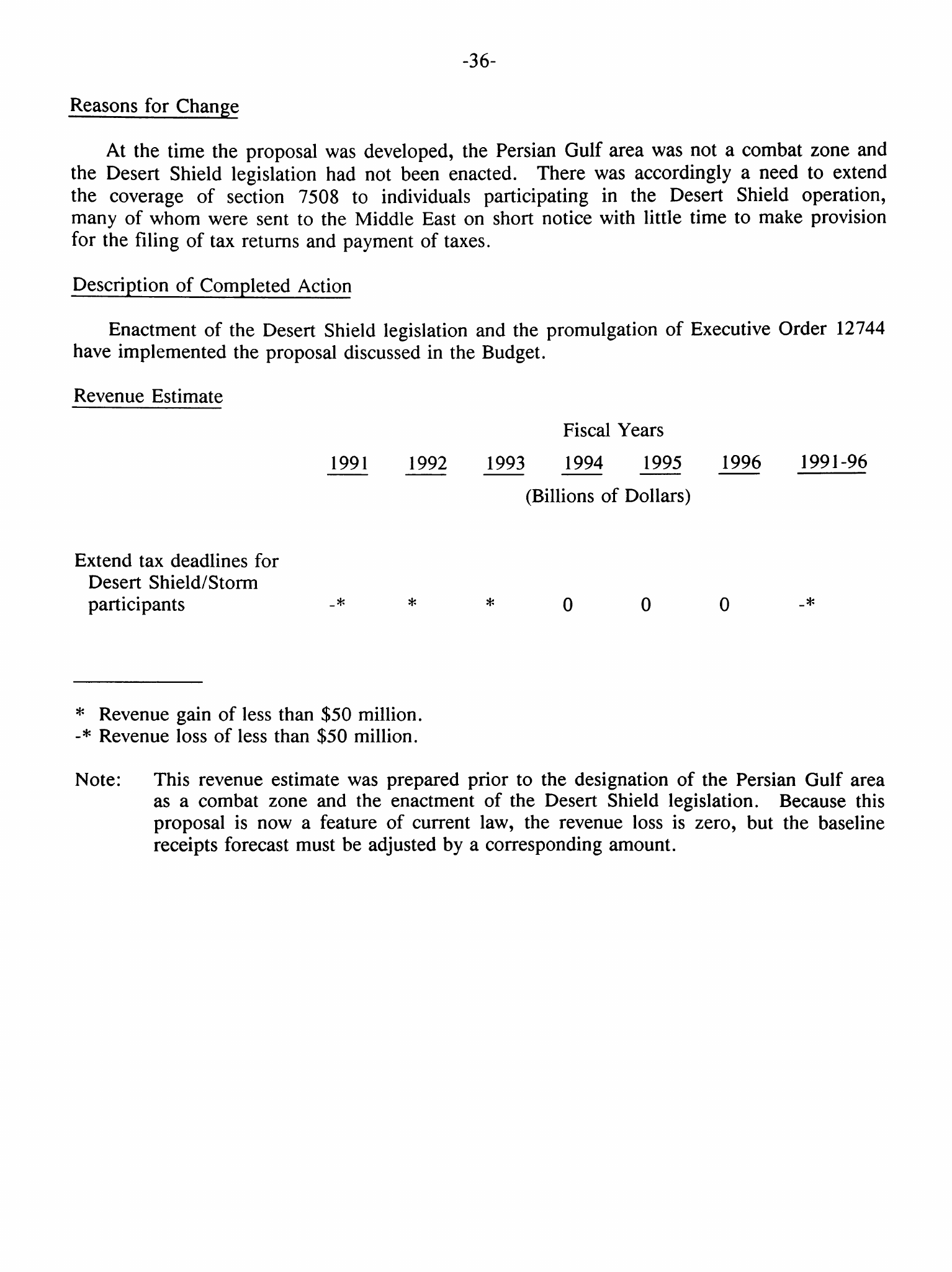

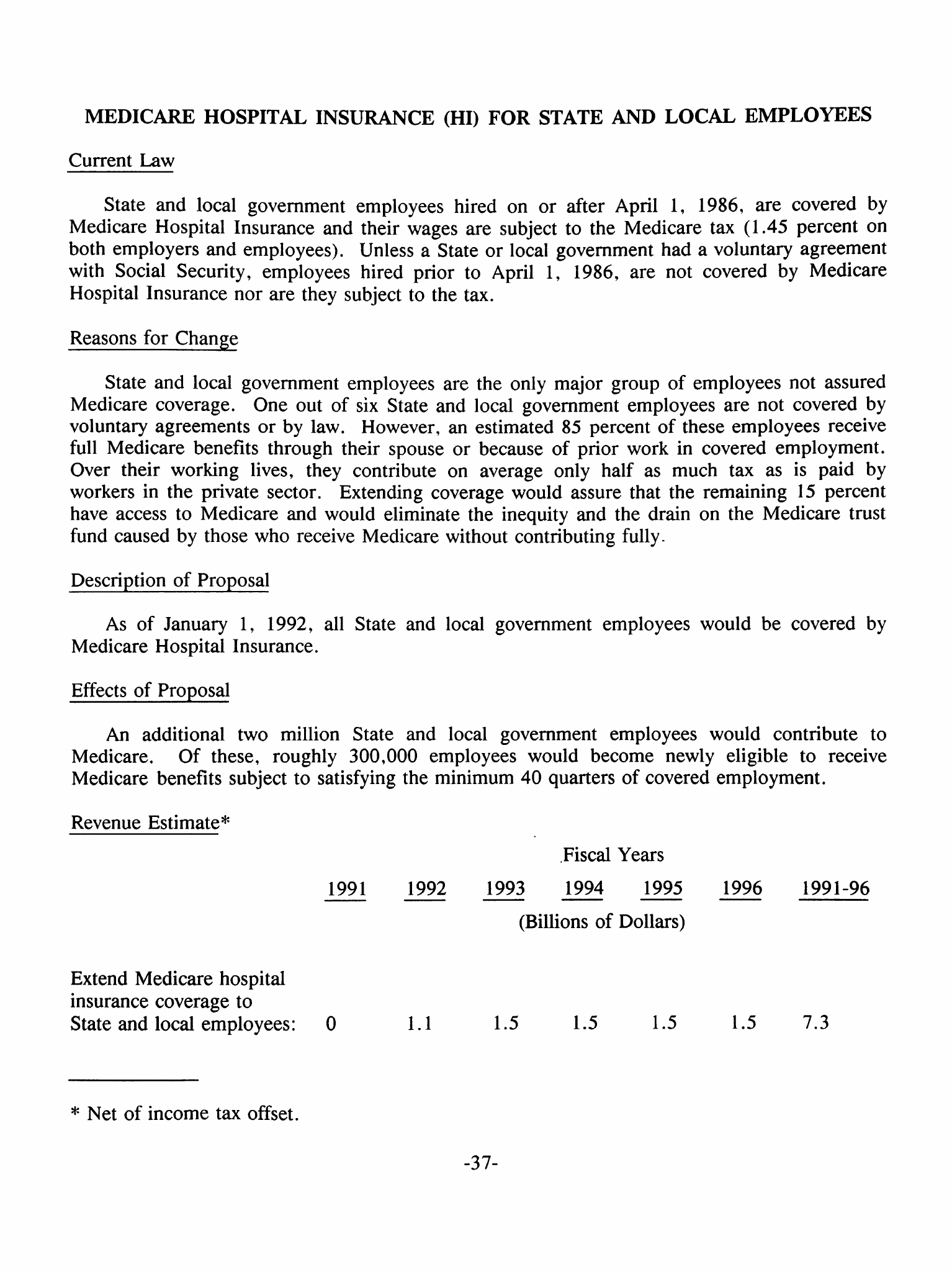

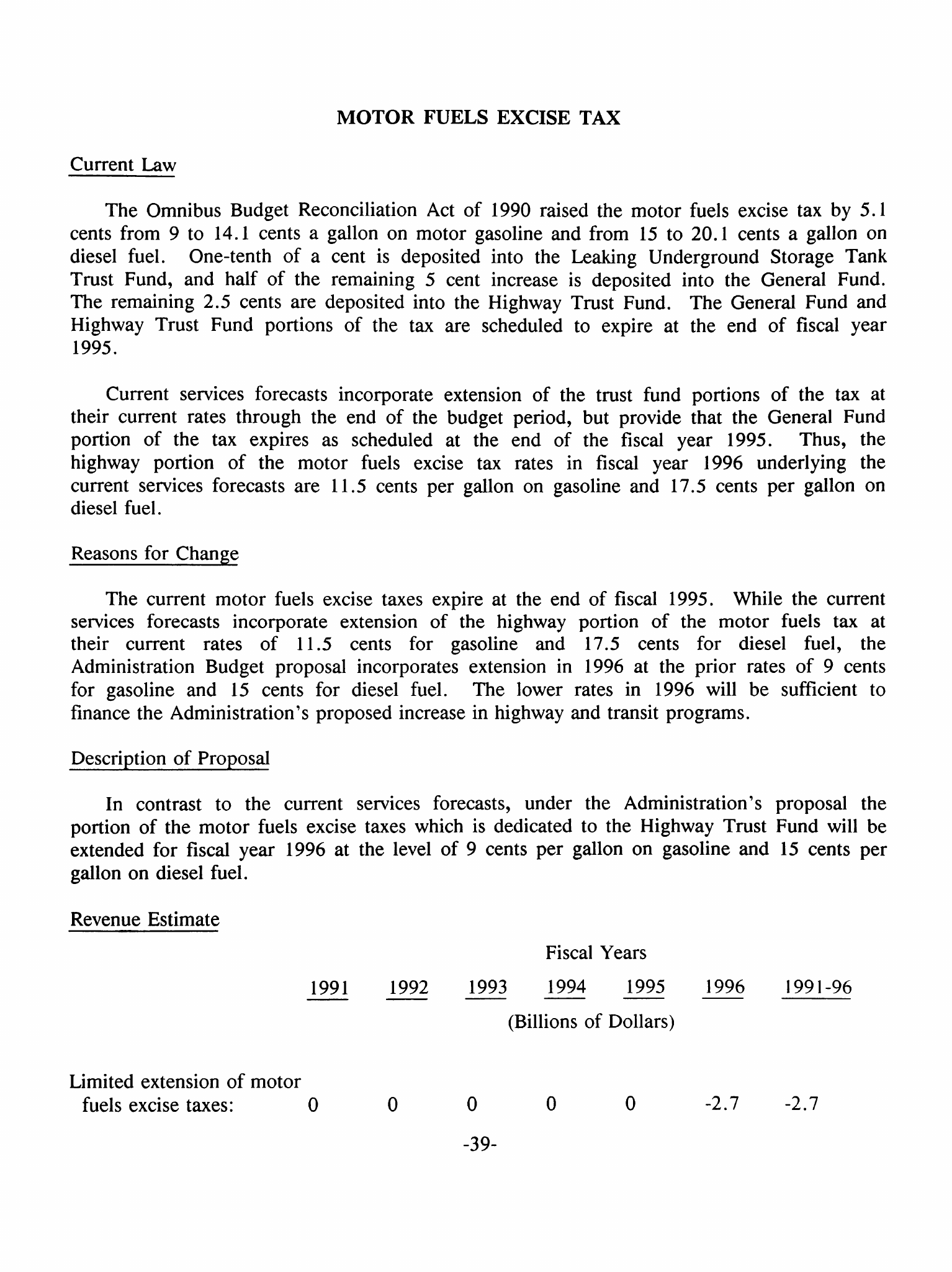

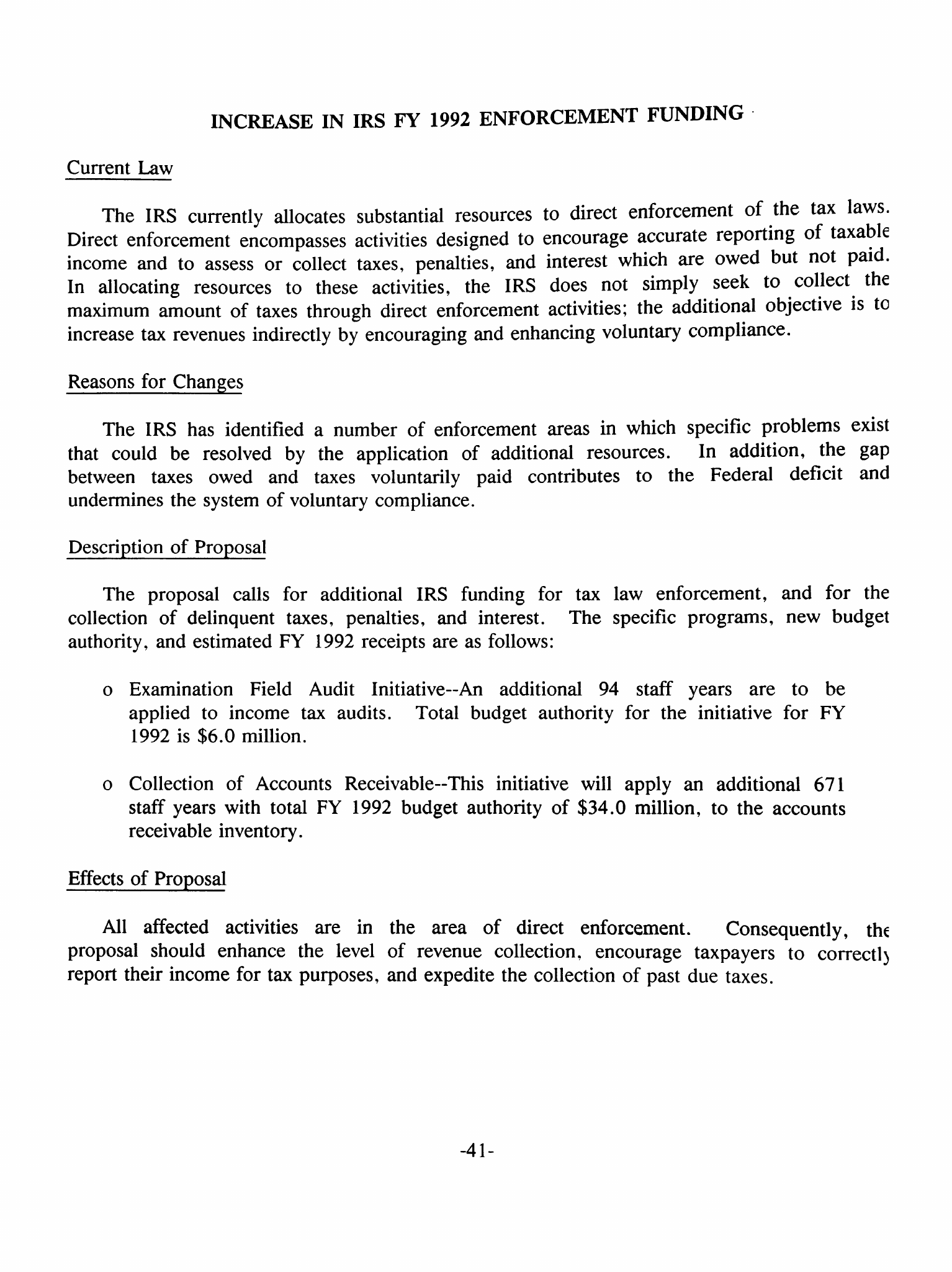

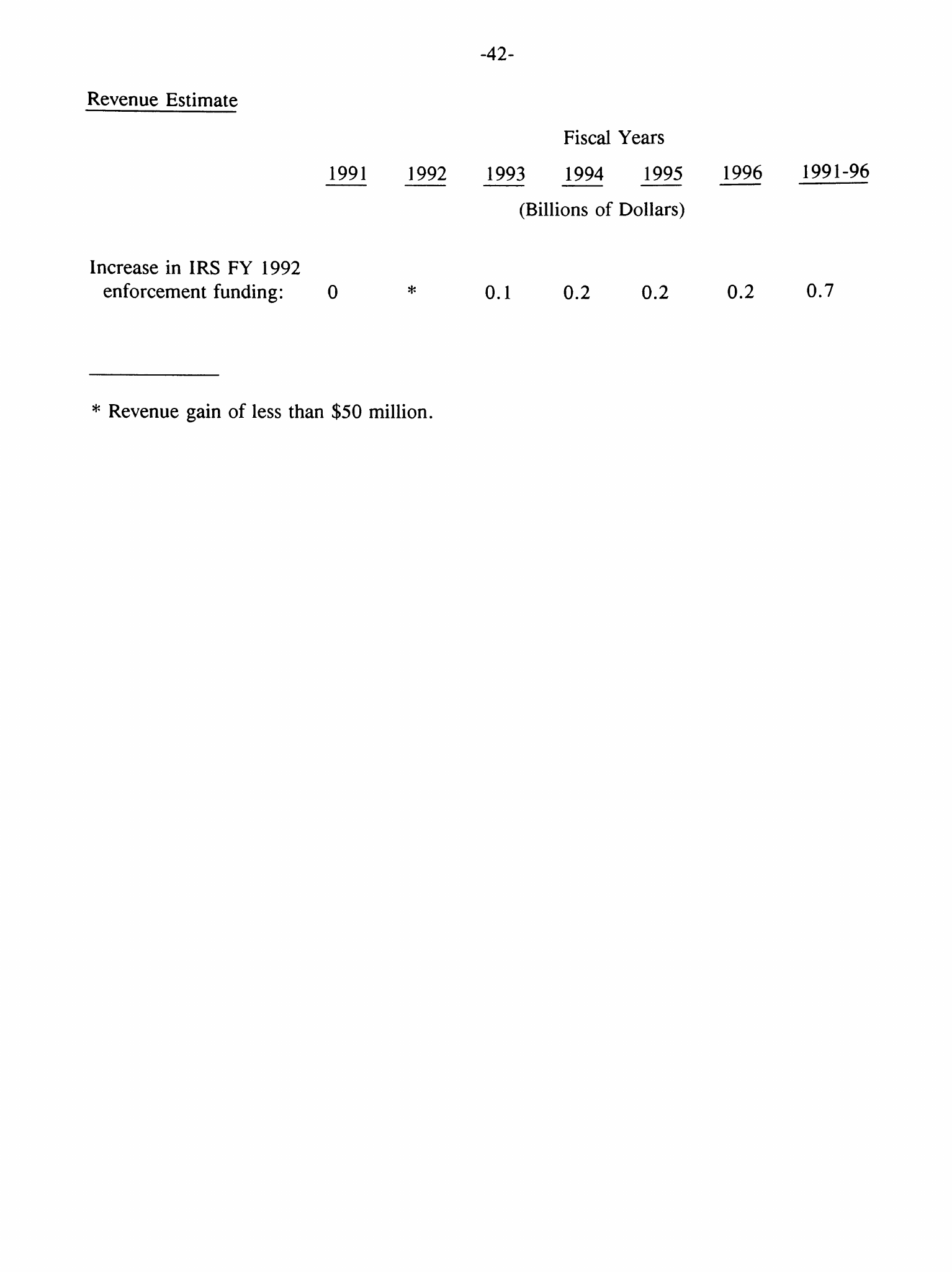

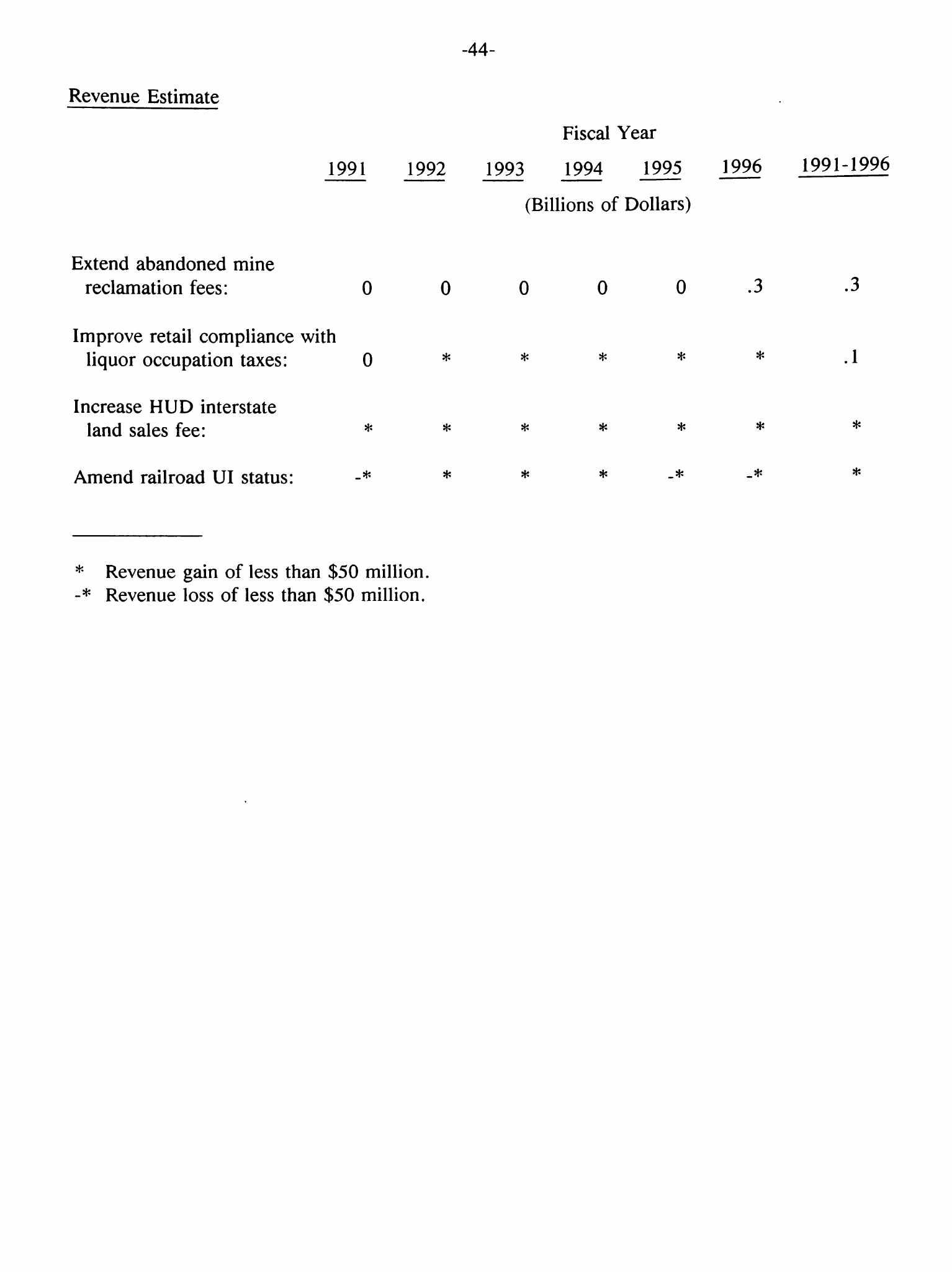

in